If you have been to the West Bank, you might know that refugees there no longer live in tents. You could even walk through a refugee camp without ever noticing, except for the many posters of those lost in the conflict. In the two refugee camps in Bethlehem, Aida and Dheisheh, there is no physical division left between city and camp, but an invisible divide remains.

“I want people from my country to come and see how I live,” said Basil, a 19-year old from Aida refugee camp. “I want them to see the wall and where we protest. But I also want them to see that we are not different from them. Just because we live in a refugee camp people automatically think we are troublemakers.”

Basil was one of the 10 participants in our Youth Innovation Fund winning project, Changing the Face of Tourism. The aim of our project was to help remove the stigma associated with refugees by providing them with training that could lead to better job opportunities and allow them to be better integrated in their community.

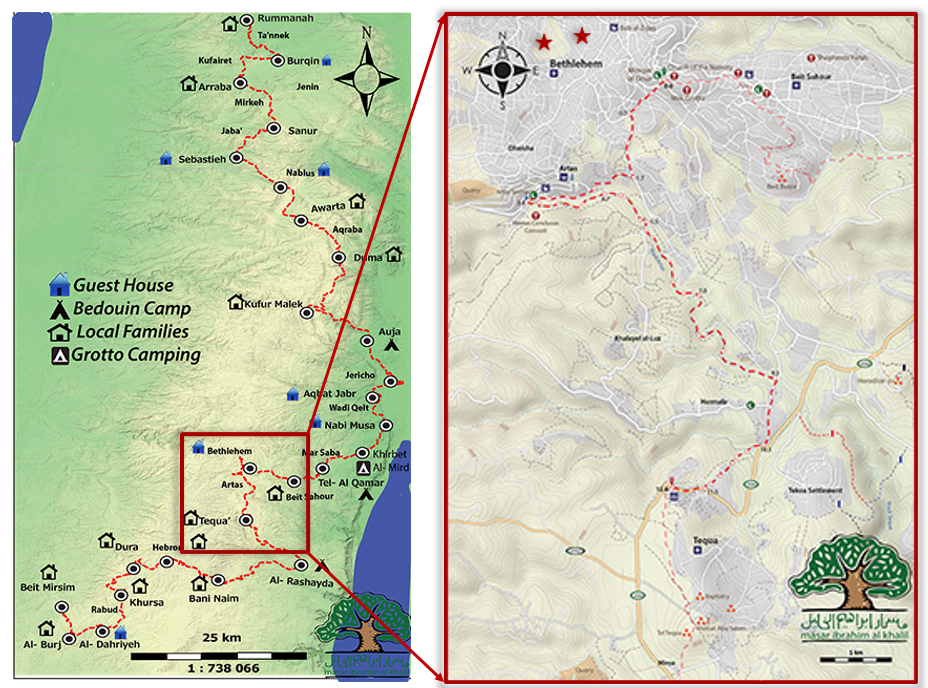

Our team looked at hiking tours on the Abraham Path, developed under an ongoing project supported by the World Bank through the State and Peacebuilding Fund. Despite the proximity of the path to multiple large refugee camps, their communities were not involved in either the tour guide training or the home visits that were part of this project.

After months of working from afar with our local partner, a non-governmental organization Masar Ibrahim al Khalil, the most exciting – and enlightening - part came when it was time for me, Raneen, to travel to the West Bank and join the 10 young refugees on one of the training’s walks from Makhrour to Battir, west of Bethlehem.

In the middle of the walk, Mahmoud, a 27-year old participant, started singing a Palestinian folk song. Minutes later everyone in the group joined in. And there we were – signing in the middle of a beautiful scenery – only a few kilometers from the congested camp and the checkpoints surrounding it.

During one of the breaks, Lamar, a 22-year old who is continuing her studies in special education, shared food she had brought from her house with all of us. We were all sitting, eating and talking, and if you had seen us from the outside, you never would have thought that most of us were meeting for the first time.

It was during these walks that I (Raneen) was able to build a connection with the participants. I no longer felt part of an international donor community observing beneficiaries. I was part of that group, spoke their language, related to their problems, and understood their frustrations. This connection translated into an open dialogue where the group confided in us and candidly provided us with feedback on the trainings and how to improve it. If it wasn’t for this connection, we might not have been able to achieve this degree of frankness and transparency, which ultimately enabled us to draw key lessons on female participation, harnessing local markets and improving social cohesion. Piloting the integration of refugee communities on a small scale enabled us to try new ideas that can now be adapted for the broader Abraham Path project, and beyond.

After the hike, Lamar invited us to her house along with others from the group. Her father joined us and shared a story about how his 13-year old son was shot six months ago during protests. You never would have guessed that the energetic girl who would bring us snacks during the hikes had just lost her brother. During lunch, which her parents insisted we all join, her father said “You asked me what I think about this project: All I care about is that she is happy. I can see it in her eyes, she comes back tired but she is happy.”

Hiking anywhere provides the means to explore nature, to walk and release some stress. In the Palestinian context, however, it can mean even more: the only chance of free movement, away from ever present checkpoints, from protests and from conflict.

Join the Conversation