People take precautions in Mali against COVID-19 (coronavirus). Photo: World Bank / Ousmane Traore

People take precautions in Mali against COVID-19 (coronavirus). Photo: World Bank / Ousmane Traore

The COVID-19 pandemic was one of the largest global shocks in recent history. Fortunately, it did not increase extreme poverty in Africa as it was feared it would . Early simulations projected an increase in the number of poor by anywhere between 30 million to 120 million in 2020. In a study using more recent data, we find that the increase was closer to 23 million in 2020. The reason for the lower-than-expected poverty increase across the continent may be a combination of things:

-

The crisis and related shutdowns affecting urban areas more than rural areas (where most of the extreme poor reside),

-

The health crisis negatively impacting older populations to a greater degree than younger ones (Africa is the continent with the youngest population), and

-

The relatively generous support available through social policy measures.

Lessons From Africa’s Experience in Weathering the Pandemic

First, states that are fragile and in conflict are relatively more affected by negative shocks compared to those not in conflict. This result is evident in Figure 1, which compares the increase in poverty in African states between those categorized as fragile, conflict-prone, or in violence (FCV) by the World Bank with those that are not. While 26% of the population (amounting to 196 million people) were living in extreme poverty in the non-FCV group of countries in 2019, 45% of the population in the FCV countries (amounting to 248 million people) were living in poverty in that same year. For the non-FCV group, an additional 11 million people were pushed into poverty in 2020 (equivalent to a 1.5 percentage point increase) and 16 million in 2021 (equivalent to a 2 percentage points increase) due to the COVID-19 pandemic. For the FCV group, the expected additional poor is about 12 million people in 2020 (equivalent to 2.1 percentage points increase) and over 14 million in 2021 (equivalent to 2.5 percentage points increase). Not only is the prevalence of poor households higher in conflict-ridden countries, but the increases due to the pandemic are also estimated to be larger and more persistent .

Figure 1: Poverty in countries with and without conflict in Africa

Source: Mahler et al. (2021) updated.

Note: FCV classification using World Bank’s FY 2021 list. FCV – Fragility, conflict, and violence.

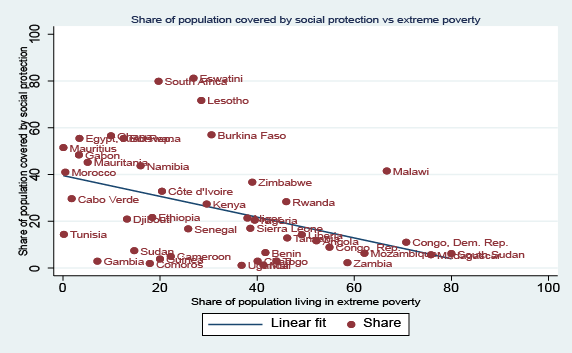

Second, the pandemic also uncovered important vulnerabilities in social safety nets in Africa. While the number of social protection programs on the continent has increased dramatically in the last few decades, their reach remains limited, with only a small share of the population covered. The coverage is particularly low in countries with high extreme poverty rates (Figure 2). It suggests that the countries may struggle to cope with large-scale future crises.

Figure 2: Coverage of social protection programs in Africa

Source: ASPIRE (Atlas of Social Protection Indicators of Resilience and Equity) database, World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/data/datatopics/aspire.

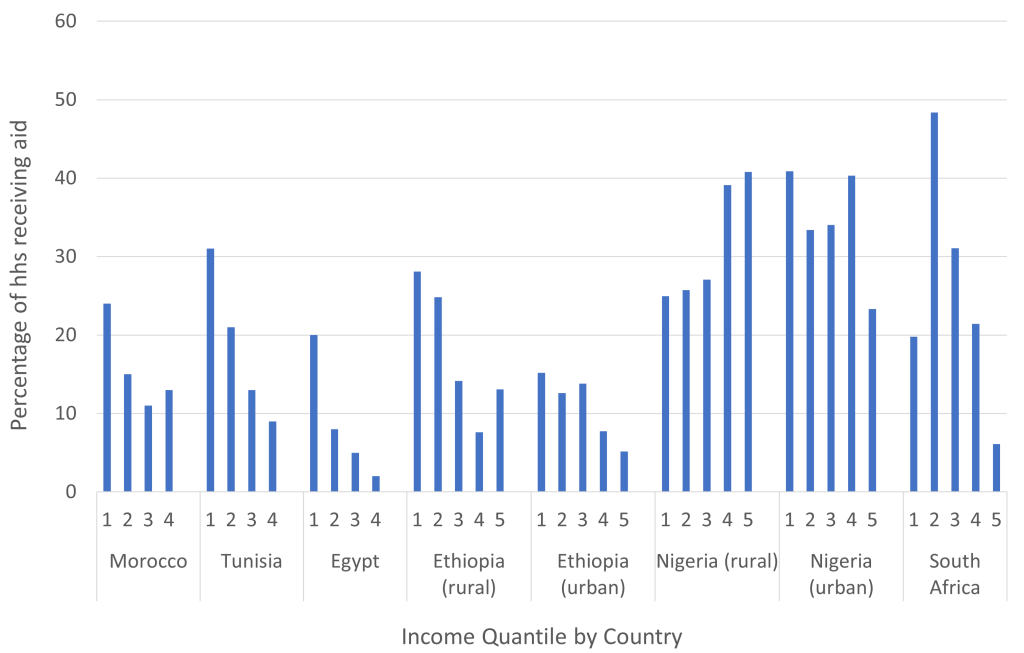

Third, the pandemic tested traditional methods of targeting and delivering social support programs in Africa which target chronic poverty—not vulnerability to shocks—and have traditionally focused on rural areas. As a result, urban households, who were disproportionately affected by the pandemic and associated lockdown measures, were not sufficiently covered by these programs. Even countries with better social protection infrastructure experienced major challenges with targeting. Analysis of the targeting of the COVID-19 social protection responses in several African countries reveals varying levels of efficiency. Figure 3 shows that social protection targeting was quite progressive in Egypt, with the poorest (pre-COVID) income quartile of households having almost double the probability of receiving assistance compared to a household at the middle of the income distribution. On the other hand, in Tunisia, a household in the poorest quartile only had 1.5 times greater probability of receiving assistance relative to the median household, and in Morocco, the poorest quartile of households were only slightly more likely to receive assistance than the median household. Targeting of the Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP) in Ethiopia during the pandemic was progressive and covered about 27% of the poorest households in rural areas but was much less effective in urban areas. In Nigeria, there was a major expansion of cash transfers, but survey data showed only mildly effective targeting of government aid in urban areas and a regressive distribution of probability of receiving aid in rural areas (Duchoslav and Hirvonen, 2021). The targeting efficiency of the social protection response in South Africa has been found to be generally pro-poor.

Figure 3: Targeting performance in selected African countries during the COVID-19 pandemic

Sources: Duchoslav and Hiroven (2022), Kohler and Bhorat (2020), and Krafft et al. (2021).

Post-COVID-19 Recovery in Africa Will Likely be Prolonged

First, inequity in access to vaccines and Africa’s slow progress in vaccination rates may drag the recovery of economies. Two years into the pandemic, only 15 percent of the African population is fully vaccinated (WHO, 2022) . Second, protracted conflicts and political instabilities, which have recently seen an increasing trend in the continent, could continue to delay recovery of economies and livelihoods. Third, the Russian-Ukraine crisis has important ramifications for food security and for food prices in African countries that rely on Russia and Ukraine for cereal and fertilizer imports.

These challenges are reminders of the need to reinforce social protection programs to protect vulnerable households. Social protection programing in Africa needs to be “shock-responsive” and evolve dynamically in response to the needs and challenges arising from covariate shocks. This requires investing in digital and data infrastructure to facilitate the delivery and targeting of social protection programs, as well as devising sustainable modalities of financing them.

The authors acknowledge financial support from the UK government through the Data and Evidence for Tackling Extreme Poverty (DEEP) Research Program

Join the Conversation