A growing body of evidence finds that cash transfers reduce violence against women and children. Photo: Sarah Farhat/ The World Bank

A growing body of evidence finds that cash transfers reduce violence against women and children. Photo: Sarah Farhat/ The World Bank

Getting a cash transfer program off the ground includes a myriad of decisions. Whether to pay benefits digitally or manually is an important decision that has gotten much attention lately. Increasingly, the evidence suggests that digital payments are the way to go.

Digital payments are more efficient and user-friendly. But what many of us probably didn’t know is that this design choice – like many others – likely also has implications for gender-based violence (GBV) within households . Paying cash transfers digitally directly into women’s accounts can allow them to retain greater control over the funds and conceal them from violent partners if necessary.

However, digital payments can be disempowering for women who lack digital literacy and their own phones, potentially putting them at greater risk of GBV. Moreover, in-person cash payments have traditionally served as occasions where women come together, interact, and learn from each other. The evidence suggests that social capital created on these occasions might help curb GBV. Social protection programs often use payment days to provide training or access to services, which may reduce the risk of GBV. One concern with the introduction of digital payments is that these opportunities for women to come together might be eliminated. At the same time, in-person payments might expose women to opportunistic harassment or violence on the way to and from payment points.

Leveraging cash transfers to prevent GBV

A growing body of evidence finds that cash transfers reduce violence against women and children – even when the cash transfer was not designed with violence prevention in mind. Research has primarily focused on the impacts of cash transfers on intimate partner violence. A few studies have examined the impacts on violence against children and adolescent girls. A recent study by World Bank colleagues looked at non-partner domestic violence, and found measurable declines. Overall, the evidence finds that the effects of cash transfers in curbing violence against women and children are overwhelmingly positive and comparable to stand-alone violence prevention interventions .

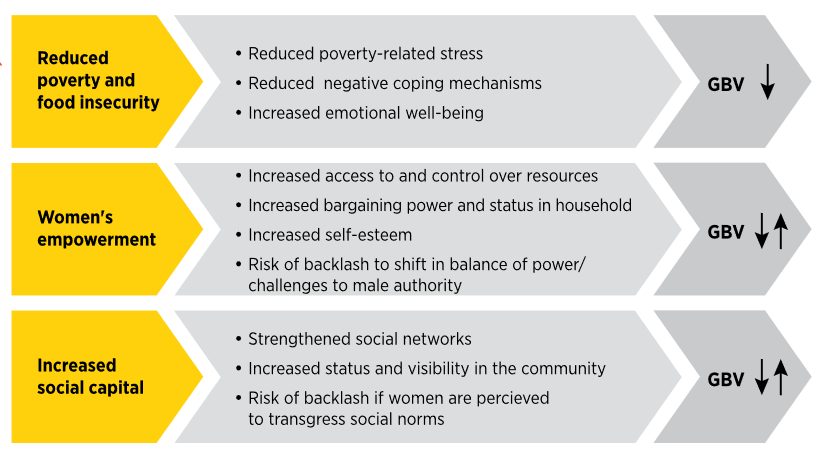

Researchers hypothesize that there are three impact pathways through which cash transfers affect GBV:

- Reducing poverty and food insecurity, thereby limiting the potential for conflict in households

- Empowering women, increasing their status in communities, and reducing their dependence on others

- Increasing women’s social capital, boosting their self-esteem, self-efficacy, and support networks.

Source: Safety First: How to Leverage Safety Nets to Prevent GBV, World Bank 2021

Understanding these impact pathways enables us to design social protection programs in a way that ‘activates’ them. If we look carefully, every step of the social protection delivery chain offers entry points to amplify the protective potential of safety nets and minimize risks. For example, during the outreach and enrollment phase, messaging can underscore that women are the intended transfer recipients, thereby increasing the likelihood that women will be able to retain control over the funds while minimizing any risk of backlash. Complementary measures such as training and coaching offer opportunities to bring women together in groups to build their social capital and self-esteem. Grievance mechanisms can be leveraged to connect GBV survivors to appropriate services.

Every design decision in a social protection program comes with opportunities and risks. The right design choice will always depend on context. Capacity constraints and institutional arrangements might limit a program’s ability to implement certain design choices. The key is to identify risks and put in place context-specific mitigation measures, such as training women to use their mobile wallets, so they are more likely to exercise control over their funds.

We have much to learn about how specific cash transfer design features affect GBV and which combinations of design features are most effective in reducing GBV. But given the encouraging general evidence and how pervasive and costly GBV is both individually and collectively, these impact pathways can help point development practitioners in the right direction .

A new e-learning course takes you through the most significant design decisions for cash transfer programs from a women’s empowerment and GBV perspective in 90 minutes, based on an operational toolkit published in 2021 entitled Safety First: How to leverage safety nets to prevent gender-based violence. The e-learning course aims to help you understand trade-offs between different design options and make choices that result in more inclusive and impactful social protection programs. Please take a look and tell us what you think in the comments below.

Join the Conversation