Moscow, Russia - April 02: A food delivery courier on the street during the period of self-isolation of citizens due to the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). © Julia Perova/Shutterstock

Moscow, Russia - April 02: A food delivery courier on the street during the period of self-isolation of citizens due to the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). © Julia Perova/Shutterstock

In the four months since COVID-19 was declared a pandemic, its toll on the health and wellbeing of people across the world has been profound. This experience has no parallel in living memory, making it essential to understand the impact of the pandemic and the effectiveness of government policies used to cope with it. Follow-up surveys of the standard World Bank Enterprise Surveys (ES) make it possible to see some of these effects in the Russian Federation. Features of the Enterprise Surveys – a representative sample of a large portion of country’s private sector and a standard methodology – allow a comparison of the Russian experience with other countries as well.

What these data show is illustrated in ten graphs, below. Firm-level follow-up survey data was collected through re-contacting businesses interviewed prior to the pandemic as part of the standard ES. Italy and Greece, where follow-up surveys were also completed, were chosen as comparators.

1. Decreases in demand were widespread among Russian firms.

71% of firms experienced a decrease in demand for their products or services. This is comparable to Italy (75%) and statistically significantly better than in Greece (81%). Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) were affected more. All sectors were affected, and while food manufacturers and some retailers were affected the least, the prevalence of a decrease in demand was still staggering (for example, 52% of food manufacturers in Russia experienced a drop in demand).

2. While the drop in sales was massive in Russia, it was greater elsewhere.

On average, firms' monthly sales fell by over a quarter (28%). While huge, this decline is relatively low compared to a 47% average plunge in Italy and a 37% fall in Greece. SMEs lost a considerably and statistically significantly higher share of their sales than large firms. Interestingly, while the prevalence of a sales decline is similar across these three countries (76% experienced a drop in sales in Russia vs. 78% in Italy), the size of the drop among those experiencing any drop is far larger in Italy, 62%, and Greece, 49%, than in Russia, 38%.

3. Layoffs were widespread, including of permanent workers.

A higher share of firms in Russia cut the total number of permanent or temporary workers than in Italy or Greece. For permanent workers, the difference with Italy was 10.1% vs. 17.5% in Russia (statistically significant at the 5% level). Cross-country differences in layoffs of temporary workers were much greater – 35.7% of firms in Russia cut temporary workers compared with around 11.5% in Italy and Greece. Such wide disparities in the prevalence of layoffs cannot be explained by reductions in total hours worked: Russian firms reduced working hours much less than in Italy, while experiencing more widespread declines in workforce.

4. Russian businesses have exhibited remarkable flexibility.

A higher share of firms in Russia than in Italy or Greece took steps to respond to the crisis. At the time of interviews (June 2020), firms in Russia had on average 20% of their workforce working remotely, compared with 7% in Italy (May-June 2020) and 2% in Greece (June-July 2020). Importantly, the sectoral composition of these economies and corresponding natural rigidities are likely to be among the reasons for these differences. All cross-country differences in the graph below are statistically significant at least at the 5% level.

5. Decreases in cash flow availability were widespread, as were delays of payments to suppliers or workers and bankruptcy filings.

In Russia, 68% of firms experienced a drop in cash flow availability. Again, SMEs were hit harder. Delaying payments is one way to survive during a crisis, and firms in Russia resorted to this tactic considerably and statistically significantly more than firms in Italy and Greece (35% vs. 12% and 8% respectively). However, among Russian firms, 6% filed for bankruptcy, compared to negligible shares in Italy and Greece.

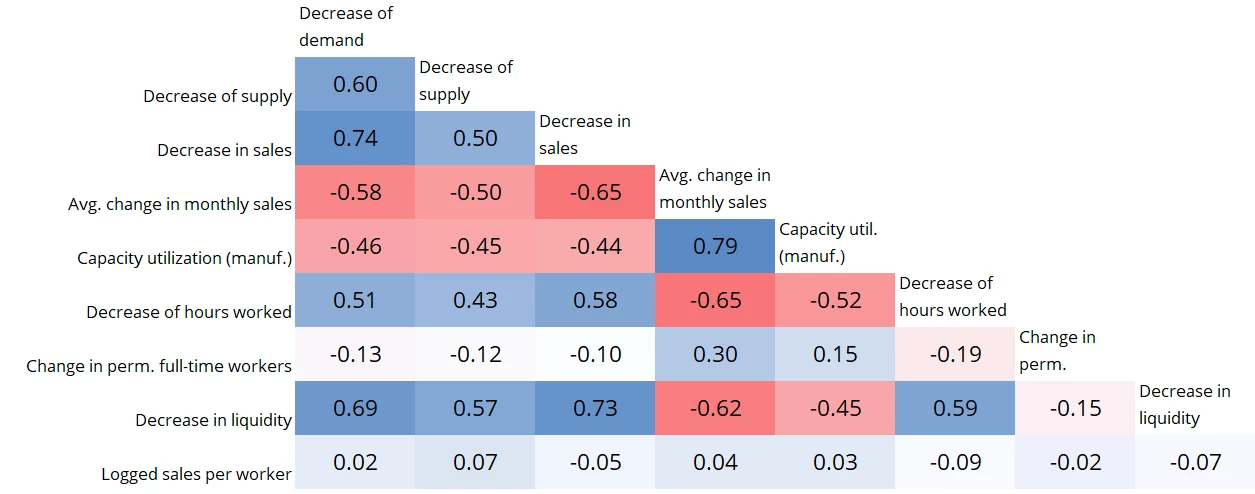

6. Many effects of COVID-19 on the private sector are highly interconnected.

While close links between demand shocks, drops in sales, cash flow availability, and employment could be expected, the degree to which these and other measures of impact are interconnected illustrates the pain of the crisis. Firms that saw a drop in demand were also highly likely to experience a drop in the supply of goods, to have considerably cut capacity, to have reduced hours worked, to have let go more permanent workers, and to have experienced decreased liquidity, among other adverse impacts. Interestingly, these shocks are not linked closely with a wide range of pre-COVID features of firms according to the baseline ES; for example, high and low productivity firms were hit equally.

7. Outward-oriented firms performed better.

Firms with an outward orientation – defined as 10% or more foreign owned, or directly exporting at least 10% of their sales – outperformed others across multiple measures. In particular, these firms underwent a considerably and statistically significantly lower drop in the size of their permanent workforce than others and were much more likely to have adjusted to the crisis. They were also less likely to have delayed payments to their suppliers. Outward-oriented firms further appear have been financially better prepared: they were less likely to use equity finance as their main way to tackle decreases in liquidity, and less likely to have received government assistance. Also, they were far less pessimistic about future prospects – none expected to be unable to recover, compared with 4% among the rest. Increased resilience to crises, even global ones, appears to be another important benefit of increasing the export capacity of the private sector.

8. Innovators were affected more, suggesting potential long-term impact.

Firms that introduced new products or services or had a process innovation (from the baseline ES) were far more likely to have decreased the number of permanent workers, potentially damaging their long-term innovativeness. At the same time and unsurprisingly, innovators were in worse financial shape – with a much higher share being overdue on obligations to financial institutions.

9. Russian firms report limited government support as of June.

While the Russian government has sought to expand its support to the private sector, at the time of interviews, the extent of this support was limited. A considerably and statistically significantly lower share of firms in Russia reported receiving assistance (8.9%) compared to Italy (27.4%) or Greece (63.4%). Even though almost twice as many Russian firms expected government assistance (17.5%) as those that received assistance, the overall share of firms that received or expected government assistance as of June 2020 in Russia (26%) was still considerably and statistically significantly lower than that in Italy (57%) or Greece (73%).

10. Fiscal relief and deferral of payments have so far been the most prevalent forms of government support in Russia.

Out of 26% of firms that received or expected government assistance, 77% received fiscal relief and 65% were allowed to defer payments, some took advantage of both. Deferral of payments covers deferral of credit payments, rent or mortgage, suspension of interest payments, or rollover of debt. Fiscal relief was statistically significantly more prevalent in Russia (among firms receiving or expecting assistance) than in Italy and Greece. Differences across countries on the prevalence of deferral of payments was less pronounced. The data also showed a much lower usage of wage subsidies or cash transfers in Russia than in Italy and Greece.

As of August, it is too early to fully assess what solutions have been more successful in coping with the crisis on the firm level or on the country level, in the short-term or in the long-term. This blog is intended to provide a quick snapshot. Deeper analysis of the Enterprise Surveys and the follow-up survey data may help answer some of these pressing questions.

Join the Conversation