Figure 1: FDI flows Reached a High of $2 Trillion in 2015

Figure 1: FDI flows Reached a High of $2 Trillion in 2015

Foreign direct investment (FDI) to developing economies dwarfs the size of official development assistance to these countries. In 2019, the respective figures were $1.4 trillion and $153 billion, a tenfold difference. In some years, for example 2015, FDI flows were nearly twenty times as large as development assistance (Figure 1). Understanding the determinants of FDI is hence a priority for generating further economic growth and post-pandemic recovery.

Figure 1: FDI flows Reached a High of $2 Trillion in 2015

Empirical studies show a positive relationship between FDI and economic development (Azam, 2010; Adhikary, 2011; Baldwin and Ottaviano, 2001; Bhavan et al., 2011; Rachdi et al., 2016). FDI raises the level of investment, it increases employment by creating new production capacity, and it promotes a transfer of intangible assets such as technology and managerial skills to the host country (Ho and Rashid, 2011). A lot is also known about the factors that attract FDI to a particular country. Multiple studies focus on macroeconomic stability, political risk, market size, trade openness, natural resources, labor cost, human capital, tax regime and state of the physical infrastructure.

We add an important factor to this extensive list by testing whether investors are attracted to economies where there are good practices in public procurement. Initial evidence shows that countries that are recipients of significant investment flows have better procurement practices in place. We find a strong correlation between FDI flows and the practice of procurement regulation (Figure 2).

Figure 2: FDI flows Are Higher in Countries with Better Practice of Procurement

Three hypotheses may explain this positive correlation. The first hypothesis is that the practice of procurement regulation is a proxy for the general development of institutions in a country. Countries with good institutions – regulatory agencies, courts, administrative authorities – attract more foreign investment. If that were the case, there would be little correlation between procurement practices and FDI flows in OECD countries, which all display good institutions; and more significant correlation among emerging and developing economies which differ in the quality of their institutions.

The second hypothesis is that business-friendly governments enhance procurement practices so that they can outsource to the private sector various services, works and goods delivery that would otherwise be done by the public sector. In particular, governments in the center-right of the political spectrum are often associated with a proclivity to reduce the size of the public administration by outsourcing tasks.

The third hypothesis is that good public procurement practices lead to more competition, less collusion and less favoritism, and in doing so increase the interest of foreign investors in participating in the local market. In other words, FDI is attracted to sectors with larger possibilities for publicly-procured contracts, as investors feel secure in having a level-playing field with domestic competitors when participating in procurement auctions. We define good procurement practices following Bosio et al (2020), who examine a new data set of laws and practices governing public procurement, as well as procurement outcomes, in 187 countries.

We test these three hypotheses in turn. For the first hypothesis to be accepted, the correlation should be weaker among the most developed economies which already have good institutions. We show that this is not the case. The correlation between FDI flows and procurement practices is positive and significant for high-income economies (Figure 3). This correlation is not statistically significant for upper and lower middle-income countries and is marginally significant for low-income countries. This analysis suggests that good procurement practices do not only proxy for good institutions.

Figure 3: The Correlation Between FDI Flows and Good Procurement Practices is Strongest in High-Income Countries

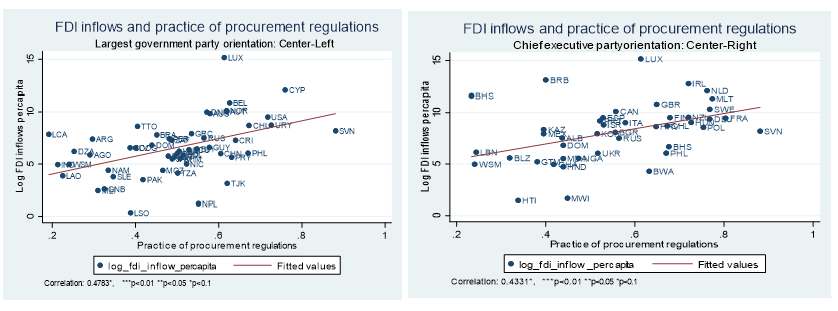

In testing the second hypothesis, we divide the sample into countries with center-right and center-left governments, using data from the World Bank database on political institutions. The database presents institutional and electoral results data such as measures of checks and balances, tenure and stability of the government, identification of party affiliation and ideology, and fragmentation of opposition and government parties in the legislature, among others. The correlation should be stronger in countries with center-right governments. When using this database, there is no difference in the correlations in countries with governments with center-left or center-right political profile (Figure 4). The difference becomes marginally significant but with the wrong sign when analyzing left and right party orientations (excluding center political formations): the correlation is positive for the left orientation parties and insignificant for the right orientation parties. The hypothesis is rejected.

Figure 4: There is no difference between countries with center-left or center-right governments

We test the third hypothesis by correlating FDI flows with the efficiency of process indicator from Bosio et al (2020) to see whether good practices lead to more completion in procurement auctions, which in turn leads to more FDI. The efficiency of procurement indicator covers favoritism, collusion, and the absence of competition in procurement. The correlation is positive and statistically significant (Figure 5), suggesting that good practices in procurement attract outside investors, above and beyond the proclivity of government to award procurement contracts and on top of the general quality of public institutions in the country. In other words, how procurement agencies apply the law matters a lot in what foreign investment the country can secure.

Figure 5: Good practices in procurement attract outside investors

These simple analyses bring us to a central point that adds to the previous literature on the determinants of FDI. General conditions like macroeconomic stability and political risk matter in the attractiveness of a country to foreign investors, but so does the implementation of specific rules, in our case procurement regulation.

Join the Conversation