One of the papers studies whether providing affordable childcare improves women’s economic empowerment and child development by analyzing evidence from Burkina Faso. Photo: Olivier Girard

One of the papers studies whether providing affordable childcare improves women’s economic empowerment and child development by analyzing evidence from Burkina Faso. Photo: Olivier Girard

This blog is a biweekly feature highlighting recent working papers from around the World Bank Group that were published in the World Bank’s Policy Research Working Paper Series. This entry introduces four papers published from November 16 to November 30 on various topics, including wage incentives, loan flexibilization and women empowerment.

The first two papers we introduce conduct fascinating experiments Latin America. In Can Temporary Wage Incentives Increase Formal Employment? Experimental Evidence from Mexico, Eliana Carranza and coauthors experimentally test whether a six-months wage incentive can increase formal employment among secondary school graduates. In Give Me a Pass : Flexible Credit for Entrepreneurs in Colombia, Xavier Giné and coauthors test the impact that loan flexibility has on revenue, profits and loan defaults.

-

Can Temporary Wage Incentives Increase Formal Employment? Experimental Evidence from Mexico tests whether a six-month temporary wage incentive can encourage Mexican secondary school graduates to obtain and stay in formal employment. Combining survey and high-frequency social security data, the paper shows that the incentive increases formal employment among vocational school graduates by 4.2 percentage points driven by a 5 percentage point increase in permanent formal jobs. Figure 1 below shows how treatment effects evolve over time. Among vocational school graduates, large and statistically significant increases in formal employment appear starting in October 2019, approximately four months after students graduate, and are maintained through the beginning of 2020.

Figure 1: Employment impacts of wage bonus treatment, by school type

-

Microcredits have been criticized by their rigidity, specifically the fixed and frequent installments. In Give Me a Pass : Flexible Credit for Entrepreneurs in Colombia the coauthors partnered with a Colombian lender that offered first-time borrowers a flexible loan that permitted delaying up to three monthly repayments. The study finds null effects for revenue and profits but increases in loan defaults. This evidence aligns with established microlender practice of offering rigid contracts to first-time borrowers.

The next two papers we introduce examine women empowerment in Sub-Saharan Africa. In The Effects of Childcare on Women and Children: Evidence from a Randomized Evaluation in Burkina Faso, Estelle Koussoubé and coauthors study whether providing affordable childcare improves women’s economic empowerment and child development. In Women Empowerment for Poverty and Inequality Reduction in Sudan, Eiman Osman and coauthors examine how gender equality has evolved in Sudan during the last decade.

-

Using data from a sample of 1,990 women participating in a public works program in Burkina Faso, The Effects of Childcare on Women and Children: Evidence from a Randomized Evaluation in Burkina Faso studies whether providing affordable childcare improves women’s economic empowerment and child development. Of 36 urban work sites, 18 were randomly selected to receive community-based childcare centers. One in four women who were offered the centers used them, tripling childcare center usage for children aged 0 to 6 years. Women’s employment and financial outcomes improved. Additionally, child development scores increased. However, the analysis finds no significant effects on women’s decision-making autonomy, gender attitudes, or intrahousehold dynamics.

-

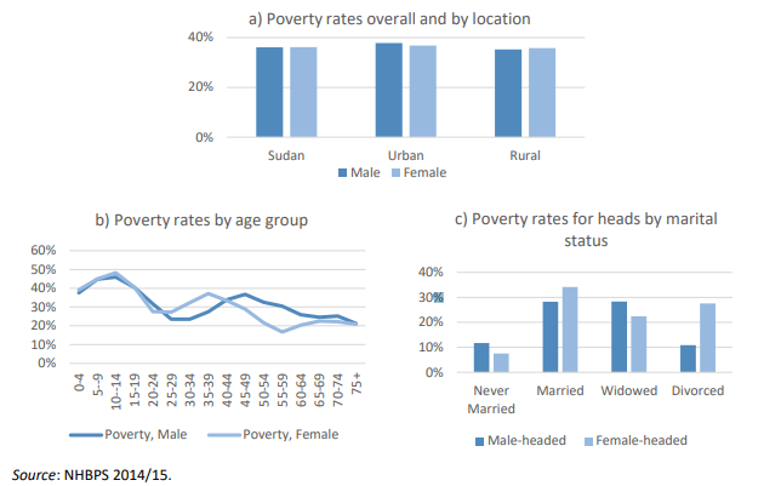

Women Empowerment for Poverty and Inequality Reduction in Sudan analyses the evolution of gender equality in Sudan during the last decade by taking a look at different dimensions. These dimensions include the accumulation of endowment in all its forms (human capital, education and health, and physical capital), access to economic opportunities, access to services (water, sanitation, and electricity), and voice/representation to make decision at all levels. The paper finds that Sudanese women are poorer than Sudanese men during key productive and reproductive years and appear to suffer greater poverty-related impacts of childcare and divorce. Figure 2 b) below shows how women in Sudan between the age of 25 and 39 are significantly poorer than men, a core period for their productivity and reproductivity. The paper also finds that when it comes to education, gender gaps are shrinking as the proportion of girls attending primary school and the proportion of boys attending secondary school both continue to increase.

Figure 2: Male and female poverty rates by location, age groups, and marital status

The following are other interesting papers published in the second half of November. Please make sure to read them as well.

- Shocks and Household Welfare in Sudan

- A Proxy Means Test for Targeted Social Protection Programs in Sudan

- Towards a More Inclusive Economy : Understanding the Barriers Sudanese Women and Youth Face in Accessing Employment Opportunities

- Reversing the Trend of Stunting in Sudan : Opportunities for Human Capital Development through Multisectoral Approaches

- Agricultural Productivity and Poverty in Rural Sudan

- Interviewer Design Effects in Household Surveys : Evidence from Sudan

- Wave Reduction by Mangroves during Cyclones in Bangladesh : Implementing Nature-Based Solutions for Coastal Resilience

- Legacies of Conflict : Experiences, Self-efficacy and the Formation of Conditional Trust

- Scarcity Nationalism during COVID-19 : Identifying the Impact on Trade Costs

- Pollution and Labor Productivity : Evidence from Chilean Cities

- Deconstructing the Missing Middle : Informality and Growth of Firms in Sub-Saharan Africa

- An Exploration of Climate-Related Financial Risks for Credit Guarantee Schemes in Europe

Join the Conversation