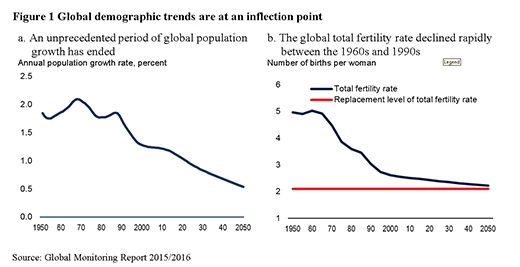

A generation ago, the World Development Report 1984 focused on development challenges posed by demographic change, reflecting the world’s concerns about run-away population growth. Global population growth rates had peaked at more than two percent a year in the late 1960s and the incredibly high average fertility rates of that decade – almost six births per woman – provided the momentum to keep population growth rates elevated for several decades (Fig 1). Indeed, the population and development zeitgeist spawned works such as Ehrlich’s 1968 book “Population Bomb,” which painted apocalyptic images of a world struggling to sustain itself under the sheer weight of its people. The policy discussion of the WDR 1984 reflected these concerns, focusing on how to feed the growing populations in the poorest and highest fertility countries, while also presenting a case for policies that would reduce fertility.

Needless to say, the global population did not continue to grow at its breakneck pace and fertility rates ended up declining precipitously, due to a range of reasons, that includes but is not restricted to improvements in living standards, access to education and female empowerment. At the same time, some of the most populous countries grew themselves out of poverty – as in the case of South Korea and China – while advances in biotechnology helped countries feed themselves, as in the case of India’s Green Revolution. The population bomb does not seem to have detonated.

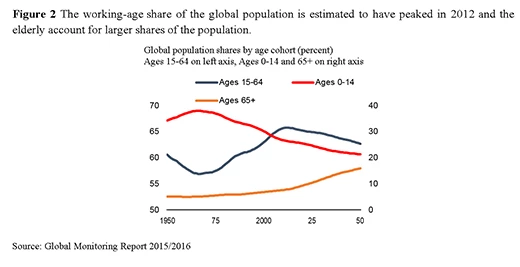

Now, more than 30 years later, the forthcoming Global Monitoring Report 2015/2016: Development Goals in an Era of Demographic Change (GMR) argues that, while the world may no longer have to fear explosive population growth, demographic change is still one of the most pressing development issues of the day. The report uses the latest UN population projections to show that global demographic trends and patterns are at a turning point, with the proportion of people aged between 15 and 64 – people most likely to be in the labor force – having reached a peak in 2012, at 65.8 percent (Fig 2). In coming decades, this share will decline, while the share of elderly – people aged 65 and up – will rise. By 2050, the elderly could account for 16 percent of the global population up from 5 percent in the 1960s.

The GMR also shows that these global trends and patterns vary dramatically across countries and levels of development. Today 87 percent of the world’s poor live in countries that will still experience burgeoning working-age population shares, and are expected to have rapid population growth. If these countries are able to accelerate their job creation to keep pace with their growing working-age population they have the potential to boost their growth and poverty reduction in coming years. In contrast, a population decline is expected for many of the engines of global growth – the economies that account for three-fourths of recent global growth. These include almost all high-income countries and several upper-middle-income countries. The shares of people over 65 years will be rising in these countries, but by making investments to boost productivity, extending the years of work, and adopting fiscally sustainable old-age support systems, they can maintain and continue to improve their incomes.

As the GMR argues, the demographic changes within countries and differences across countries present real opportunities to boost growth and poverty reduction. In particular, freer capital flows, migration and trade can help respond to growing demographic imbalances globally. With demography-informed policies, countries – old and young, developing and developed – have the chance to turn the past fears of the population bomb into development opportunities for the future.

Join the Conversation