Without the fiscal response to the COVID-19 pandemic, poverty in 2020 would have been 2.4 percentage points higher. Photo: Ezra Acayan / World Bank

Without the fiscal response to the COVID-19 pandemic, poverty in 2020 would have been 2.4 percentage points higher. Photo: Ezra Acayan / World Bank

This is the fourth blog in a series about how countries can correct course and make progress in global poverty reduction. For more information on the topic, read the 2022 Poverty and Shared Prosperity Report.

The fiscal response to the COVID-19 pandemic was unpreceded in scale, with the goal to save lives and livelihoods amid a rapidly unfolding global health, social, and economic crisis. Without this support, poverty in 2020 would have been 2.4 percentage points higher, according to the 2022 Poverty and Shared Prosperity Report, which presents a first global assessment of the impact of this response on households.

Figure 1: Fiscal policy reduced the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on poverty, but less so on poorer economies

Source: PSPR 2022

What can we learn from this global experience? And how can developing countries better prepare fiscally for another major crisis so that adequate support is provided in a timely and targeted manner?

We outline three key lessons from the pandemic experience. Learning these lessons now is imperative — not only are we in the throes of a global inflation crisis but every year climate-related and conflict-induced crises affect many households and hamper efforts to reduce poverty and build shared prosperity.

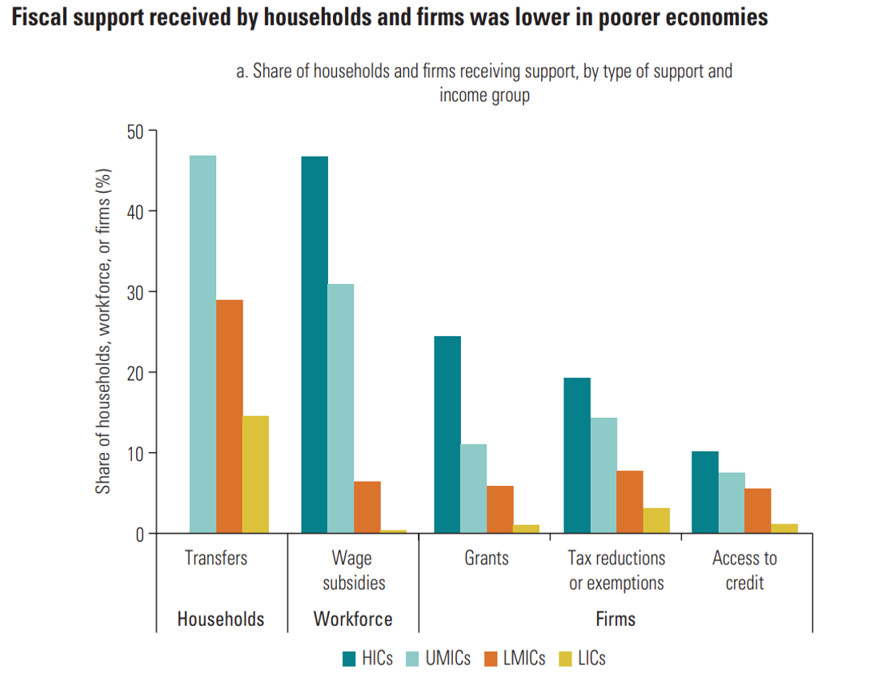

Financial Planning

The great financing divide can explain much of the difference in the impact of fiscal policy across countries. In 2020, high-income countries spent, on average, 8.1 percent of their GDP on additional non-health measures to mitigate the impacts of the pandemic. Upper-middle-income countries spent less than half of that amount, at 4 percent, while low-income countries spent just 2.1 percent. In per capita terms, the disparity in the fiscal response is even starker. Almost half of the households in upper-middle-income countries received cash transfers, compared with 15 percent in low-income countries. In upper-middle-income countries, 43 percent of firms reported receiving support in the form of wage subsidies, grants, fiscal exemptions, or access to credit. In low-income countries, only 6 percent of firms reported receiving such support.

Source: PSPR 2022

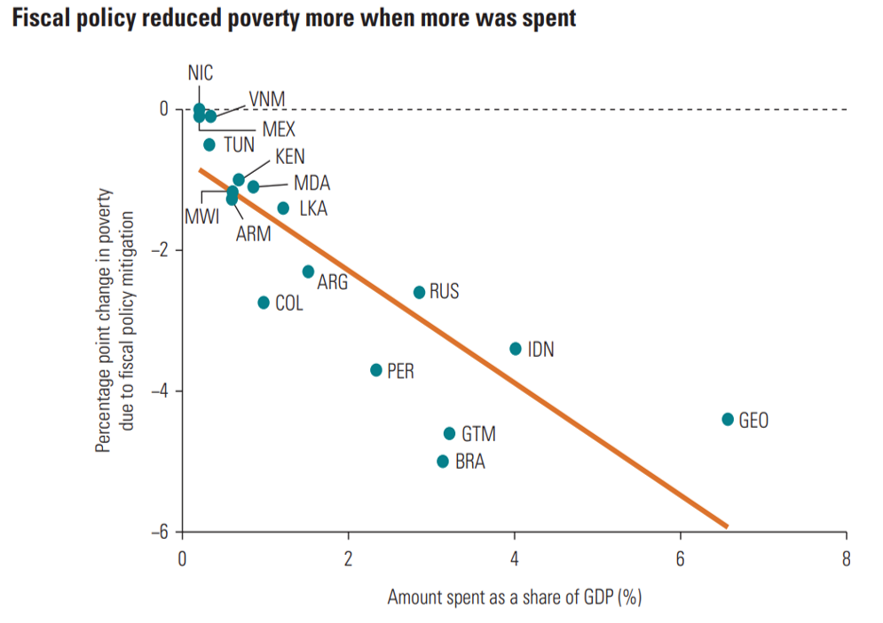

The correlation between the amount spent on the response and the impact of the response on poverty is very high, explaining about 70 percent of the variation in impact.

Source: PSPR 2022

For many countries, the amount spent was a very constrained choice, largely determined by their ability to take on new debt. High borrowing costs limited the scale of the COVID-19 fiscal response in many low- and lower-middle-income countries . In low-income countries, international support accounted for the vast majority (95 percent) of financing the fiscal response. It was also a major source of support for lower-middle-income countries (73 percent) and upper-middle-income countries (50 percent).

Crisis financial planning can help countries be better prepared by equipping them with a strategic plan for using contingency instruments, risk transfer instruments, reserve funds, and budget reallocation plans to deliver the amount and timing of financing required. Reserve funds are a low-risk layer for more frequent crises; contingent credit and market-based risk transfer instruments are better suited for events of higher magnitude and less frequency.

Governments will likely continue to rely on borrowing and budget reallocations in major crises, even when prearranged finance is in place. Good debt management is necessary in advance of a crisis to ensure that low-cost borrowing is available. Budget reallocations should be rules-based and, to the extent possible, predictable, and conducted in a consultative way to maintain budget credibility and minimize opportunity cost without compromising the speed with which reallocations can be made.

Informal Economy

The pandemic response showed that reaching households and protect jobs in informal economies is challenging. The share of workers at firms receiving wage subsidy support was larger in countries with a greater share of formal workers in the economy before the crisis— even when controlling for the overall level of spending and GDP per capita. Reaching affected households quickly was also harder in countries where automatic stabilizers such as unemployment insurance covered only a small share of formal sector workers.

Therefore, where the informal sector is large, there is a need to increase the use of alternate automatic stabilizers. This may take the form of employment guarantee schemes, such as in rural India, for example. Or transfers indexed to weather or prices, such as in the Kenya Livestock Insurance Program, which protects pastoralists in northern Kenya from drought.

Delivery Systems

To provide support quickly and effectively in a crisis, it is recommended that countries invest in delivery systems that can better identify the people who have fallen into poverty because of the shock, and not just those living in chronic poverty. In many low-income and middle-income countries, it was several months into the pandemic before transfers reached recipients, even though income losses and rising food insecurity had taken hold from the outset. When digital payment systems were present, however, delivery was much quicker.

A major challenge was reaching vulnerable households experiencing income loss who were not typical beneficiaries of social protection systems, especially in low-income and lower-middle-income countries. Some countries did manage to build innovative delivery systems very quickly – South Africa and Togo, for example. But the cost was often high for many countries without systems to identify and target those urgently in need. Under pressure to quickly provide broad income support, low-income and lower-middle-income countries were more likely to implement subsidies alongside targeted transfers – even though a greater share of subsidy support goes to the better-off.

This has critical implications for developing crisis delivery systems. Investing in national IDs, social registries, and digital payment systems can all speed up delivery. More fundamentally, however, there is a need to build in automaticity to transfer programs. This would allow programs to be scaled up automatically through pre-approved protocols backed by social registries, open enrollment protocols, and digital payment systems in response to a burgeoning crisis.

Aligning Incentives to Prepare for Crises

The constant need to meet more immediate fiscal demands makes it challenging for governments to allocate sufficient funds to prepare for a potential future crisis. International humanitarian and development organizations also do not incentivize crisis preparation when providing cheaper finance for crisis response when a crisis is underway. Yet, not preparing means that, when a crisis does strike, a country’s fiscal response will likely be slow and inadequate – with real consequences for the poor and most vulnerable in society.

Development loans and grants to countries are an opportunity to incentivize proactive financing. They help governments prioritize the right risks, respond to clear needs transparently and objectively, complement ongoing initiatives, and align with strategic priorities. A good example is the Crisis Response Window for Early Response Financing from the International Development Association (IDA), the World Bank’s fund for the poorest countries. Expanding such approaches to incentivize countries to undertake crisis preparedness can enhance recovery and protect future gains in poverty reduction.

Join the Conversation