Flore de Preneuf / World Bank

Flore de Preneuf / World Bank

In Bukavu, Democratic Republic of Congo, the Director of the civil society organization “L’Observatoire de la Parité” recently refuted a man who was convinced that he held the power to grant his wife permission to work. “This time is over,” she told him. But before 2016, he was right: a Congolese woman could not complete any legally binding acts without the authorization of her husband. From the enactment of the first Family Code in 1987 until its revision in 2016, a woman’s right to choose where to live, sign a contract, get a job, and open a bank account were restricted and she was legally required to obey her husband (figure 1).

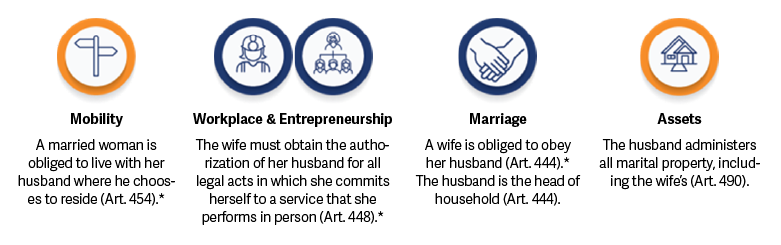

Figure 1: Legal restrictions in the 1987 family code

* Restriction was removed with the 2016 reform of the Family Code.

The recent Women, Business and the Law case study “Reforming for Gender Equality in the Democratic Republic of Congo: From Advocacy to Implementation” discusses how these reforms came about. In collaboration with local women’s rights experts, the authors identified three success factors that made passing this law possible: gender champions across local civil society groups; government and international actors making the economic case for reforming discriminatory provisions; and international obligations that allowed the reforms to pass.

While women’s rights groups had been pushing for legal reform for almost 20 years, there was much resistance amongst the predominantly male lawmakers in the Senate and National Assembly. These women’s rights groups—together with international actors, including World Bank staff—presented evidence on how the Democratic Republic of Congo was lagging in reforming their laws compared to other countries in the region, including Benin, Burkina Faso, and Togo. Evidence of beneficial outcomes for Congolese society through increased economic opportunities for women, without negative repercussions on family life and social cohesion, also proved particularly powerful in convincing skeptics .

Thanks to the groups’ continuous meetings, and within the right context for change, major reforms to the family code were enacted in 2016, more closely aligning the country’s legal framework with its obligations under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women.

The elimination of marital authorization for women’s access to employment, bank accounts, and loans, instantly made it easier for women to explore new economic opportunities . Yet, despite these positive effects, the study also highlights the remaining challenges for women to successfully enjoy their new rights (figure 2). Notably, a general lack of resources for dissemination and implementation of the law, low female representation, and constraining societal gender norms continue to act as major hurdles toward gender equality.

Figure 2: Remaining challenges

To support the effective implementation of the 2016 Family Code, the World Bank financed the Small and Medium Enterprise Development and Growth Project, which promotes gender-friendly business regulations and provides targeted support to women who are self-employed, subsistence entrepreneurs, and those running home-based or family-owned businesses. Important lessons emerge from this support:

-

Cultural barriers and gender norms that prevent the uptake and implementation of progressive legislation can be addressed through behavioral change campaigns (e. g. social marketing campaigns) that include community leaders, local governments, and successful women entrepreneurs who can serve as role models. Digital technologies and media also offer an effective dissemination platform that can shift behavior over time, especially among younger generations.

-

Proven models for empowering women, like Personal Initiative (PI) training that has been shown to bring remarkable growth to female-owned small businesses, can be adapted to local context. For example, an ongoing impact evaluation includes a version of the PI training offered simultaneously to husbands of female entrepreneurs. Early results show increased attendance by women entrepreneurs when their husbands were also invited to attend.

-

Even with the new legislation, public officials and the private sector continue to apply obsolete and discriminating rules. The case study outlines the example of commercial banks, especially in the provinces, that still require the husband’s written permission for married women entrepreneurs to open bank accounts. Capacity development (e. g. gender-sensitive training of credit officers) demonstrated some results under the ongoing project, but broader efforts are needed, including development of financial instruments that cater specifically to the needs of women entrepreneurs.

The existing project demonstrated positive results for women beneficiaries and generated considerable demand, especially for PI training and access to finance. A new project, Empowering Women Entrepreneurs and Upgrading MSMEs for Economic Transformation and Jobs in DRC, will bring $300 million to scale up the focus on economic empowerment of women in four additional locations. The Democratic Republic of Congo example shows that not only are reforms needed as a first step to grant women legal rights, but that implementation efforts and follow-up are essential if these changes are to have a strong and long-lasting impact on women’s lives .

Join the Conversation