Across the globe, women are largely employed as informal, off-the-books workers or as owners of unregistered firms, and frequently fall outside the individual income tax net. Stephan Bachenheimer/World Bank SB-NP01

Across the globe, women are largely employed as informal, off-the-books workers or as owners of unregistered firms, and frequently fall outside the individual income tax net. Stephan Bachenheimer/World Bank SB-NP01

The World Bank Group’s Women, Business and the Law project assesses legal discrimination against women to inform policy discussions. Taxation, not yet included in the dataset, offers an objective and measurable benchmark for global progress towards gender equality.

The important linkages between tax policy and gender equality are well documented. Taxation can alleviate or reinforce gender gaps in paid employment, unpaid care work, and income . To minimize any negative effects of tax policy on women, especially in terms of their economic empowerment, it is crucial to take stock of the interplay between tax and gender as well as how tax policy can be used to work towards broadly desired socio-economic outcomes, such as the increased labor force participation of women. Raising maximum revenue in a predictable and dependable way is also crucial to support expenditures on policies that promote gender equality in a variety of areas, including health, education, infrastructure, social protection, and sanitation.

There is evidence that many women have lower incomes, higher unpaid care burdens, and fewer assets. Such underlying differences between men and women in their employment and economic activities have important tax implications. Across the globe, women are largely employed as informal, off-the-books workers or as owners of unregistered firms , and frequently fall outside the individual income tax net. Also, men are more likely than women to gain higher incomes, often due to discriminatory laws such as those measured by Women, Business and the Law. Women are less likely to be registered entrepreneurs, and frequently are outside the corporate income tax net, but their businesses may be subject to presumptive taxes. Women are additionally less likely to hold formal titles to assets and property. Finally, women have different consumption patterns, and tend to purchase more basic necessities (health, education, and nutrition).

Comparative analysis of taxation and gender equality across regions and countries is rare, aside from the recent OECD stock take of national policies for a subset of 43 economies, an assessment for 16 economies in Africa and an ongoing study in Asia and the Pacific. Given this information vacuum, we lack a global picture of how women are treated by tax policies and cannot undertake a comparative analysis of the different dimensions of gender equality in the legal fiscal frameworks across countries and regions . Collecting this missing data could help to identify good practices that influence women’s prospects in the labor market.

The Women, Business and the Law team aims to close this knowledge gap by undertaking a legal review of the gender dimensions of fiscal frameworks, focusing on the most relevant areas of taxation that exacerbate gender inequality (both explicit and implicit gender biases), as well as examining trends in gender-responsive tax policies that promote gender equality. A broad geographical scope would facilitate the examination of regional developments in gender equality in taxation and the identification of remaining policy gaps at the national level.

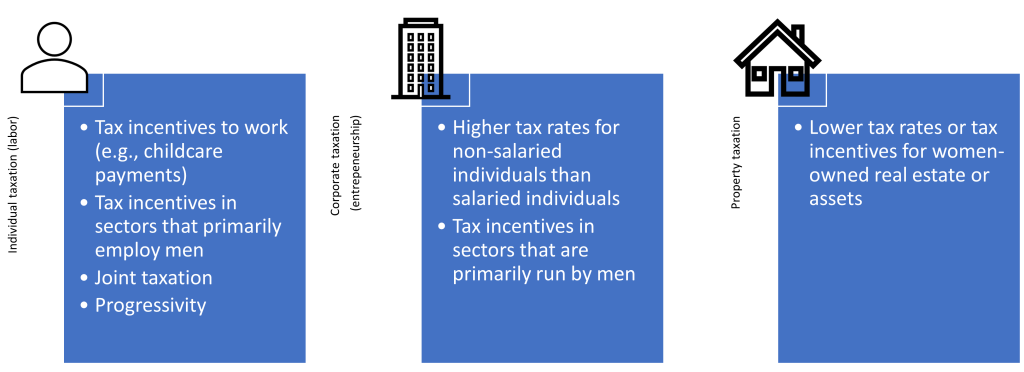

The research would focus on discriminatory and good practices in three key areas: individual taxation, corporate taxation, and property taxation.

Individual taxation of labor income is the most important tax policy to look at from a gender perspective. Policies related to the tax system’s progressivity, the unit of taxation, and how the tax base is defined can all impact women’s participation in the labor market. There are several dimensions of individual taxation that the Women, Business and the Law team could shine a light on:

· Tax credits, deductions, allowances, and public services such as childcare and education create important incentives to work. For instance, of major importance from a gender perspective is whether there are tax incentives for childcare payments and whether these incentives are specific to men or women. Childcare responsibilities may force women to leave the labor market, at least temporarily, or opt for part-time work—both of which have long-term implications for human capital accumulation and lifetime earnings.

· Tax incentives in individual taxation and who benefits from them also need to be documented. Second earners (generally women) are highly sensitive to incentives to work created by tax policies. This is particularly true for mothers with young children. Countries continue to have individual income tax incentives that implicitly discriminate based on gender in sectors that primarily employ males, e.g., military severance payments, business trips, night shifts, or overtime hours.

· Joint taxation is important as it may result in a higher effective marginal tax rate on secondary earners. Whether taxation is done at the individual or household level has important implications for work incentives for the lower-paid earner in a two-earner household. Under household-level taxation policies, income maximization may only be achieved if one household member (typically the woman in heterosexual couples) opts out of the workforce.

· There are also gender dimensions to the progressivity of tax systems. Single-rate tax systems may simplify income taxation but rarely benefit individuals with no or low incomes (disproportionately women). More progressive taxes can reduce income inequality between men and women and incentivize people at the lower end of the earning distribution to participate in the labor force .

Corporate taxation has important gender implications as the corporate world is not gender-inclusive, and female employees are more concentrated in certain sectors. There has been a trend toward the incorporation of businesses, fueled in part by cuts to corporate income taxes that make it more beneficial for businesses to be incorporated (corporate taxes are now generally lower than personal income taxes). Women-led-businesses have not kept pace with the trend toward incorporation and are disproportionately unincorporated. There are two critical issues that Women, Business and the Law could analyze.

· Further research is needed on whether there are flat corporate income tax rates or low progressivity, which results in poorer people - the majority of whom are women – facing higher marginal tax rates and, as a result, having lower incentives to work more. Because of underlying gender differences in entrepreneurship, lower corporate taxes compared to labor taxes gives disproportionate benefits to men and creates distortions on how taxpayers earn income. Corporate tax benefits may be granted for particular sources or certain types of businesses, particularly in sectors where men are disproportionately represented, and this should be assessed and documented on a global scale.

· Corporate tax incentives may promote gender equality or exacerbate inequalities, which should be understood and documented. For example, lower corporate tax rates can be offered to firms or sectors that employ more women, and employers that accept such incentives may, in turn, be required to ensure improved working conditions and facilities for female employees (mothers, in particular). On the other hand, corporate tax incentives may implicitly exacerbate gender inequalities if men are more likely to benefit from them. This is likely the case with capital gains exemptions and tax breaks for investment.

Property tax and stamp duty concessions have been successfully applied to increase women’s property ownership. This matters because women are much less likely than men to own property (for legal reasons and social norms), which has important implications for empowerment, intra-household bargaining power, household expenditure, as well as health and education decisions.

· Women, Business and the Law could assess and document whether tax systems grant lower tax rates or tax incentives for women-owned real estate or assets. Such policies might incentivize registering property in women’s names, thus raising their control over assets.

It is worth noting the absence of indirect taxation from the forms of taxation discussed above. It is well established that VAT is regressive and, in its regressivity, the VAT burden also falls disproportionately on women. However, a lack of gender-disaggregated consumption data will impede our efforts to look at the gendered implications of VAT. So, while the gender biases may be large, we propose leaving this area to future research efforts. On the other hand, policies exempting certain services (such as childcare) and products (such as feminine hygiene products) from VAT may be easier to uncover and assess, and we propose considering them in the proposed data collection efforts. Similarly, it may be feasible and desirable to include the gender implications of wealth, inheritance, and trade taxes.

Thoughts looking forward

Although this data collection might be challenging, given that publicly available information and legislation differ widely across countries, any movement toward closing this data gap is vital for promoting gender equality. Women, Business and the Law has made significant progress by shining a light on discriminatory laws to encourage reform. This success could be expanded to the area of tax law by providing a global picture of the provisions in tax codes that directly target women’s empowerment.

To that end, feedback from colleagues, peers, and experts on this new research agenda is welcome. We look forward to working together to successfully analyze the gender dimensions of fiscal frameworks across countries.

Join the Conversation