Well-designed labor market policies will play an even more critical role during the post-pandemic period to rebuild a more inclusive and resilient global economy. Photo: Shutterstock

Well-designed labor market policies will play an even more critical role during the post-pandemic period to rebuild a more inclusive and resilient global economy. Photo: Shutterstock

Increasing uncertainty in the global economic environment, accompanied by high unemployment rates and declining income share of labor around the world, has increased the need for labor market policies. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic until the end of 2021, World Bank’s Social Protection and Jobs Policy Inventory recorded 5,633 labor market measures of governments, including wage subsidies, cash transfers, training, unemployment benefits, and support for financial obligations, among others.

Well-designed labor market policies will play an even more critical role during the post-pandemic period to rebuild a more inclusive and resilient global economy. However, data on both passive and active labor market policies needed to improve the effectiveness of these policies are available only in a handful of developed economies. To partly address this data gap, we collected novel data on selected unemployment benefits (UB) and active labor market policies (ALMP) in 191 countries in 2019 and 2020 and provided the data analysis in a recent paper.

According to new data, in 2020, 48 percent of economies had a UB scheme, and 82 percent had some form of ALMP . Until the cutoff date of May 1, 2020 for recording reforms, only 12 countries implemented reforms on the areas of UB and ALMP covered by the data. On average, countries with a UB scheme required a minimum of 11.5 months of contribution to become eligible for UB and offered a maximum of 37.5 weeks of UB to eligible employees of 1-, 5- and 10-year tenure. Not surprisingly, both the UB scheme’s availability and average duration increase with income levels, while the minimum duration of contribution tends to decrease (Figure 1). Among regions, OECD high-income and Europe and Central Asia (ECA) have the highest percentage, while Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and South Asia (SAR) have the lowest percentage of countries with the UB scheme.

Figure 1. UB scheme, UB duration and minimum contribution period for UB, 2020

Source: World Bank Group.

Note: Total sample size is 191 for UB schemes and 91 for the other two indicators. See Table A2 in the appendix of Ulku and Georgieva (2022) for the sample size of each category.

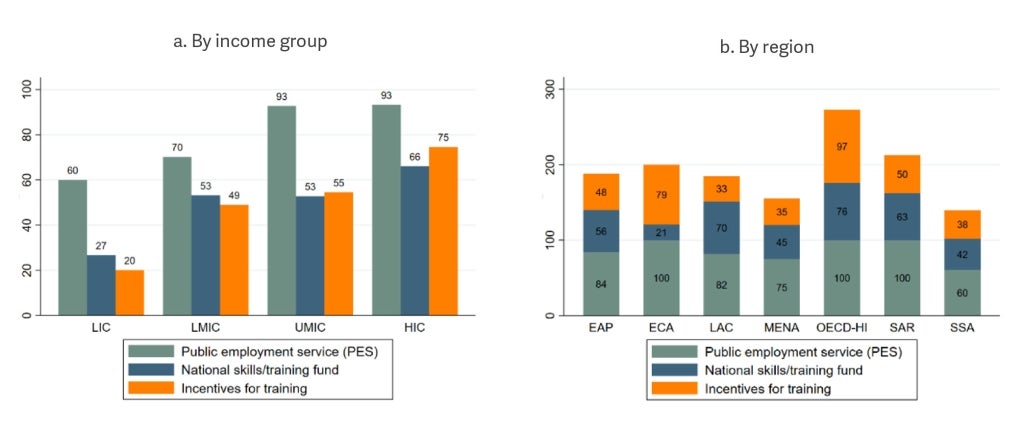

Regarding ALMP covered by the data, public employment services (PES), national skills fund, and incentives for training are available in 82, 53, and 54 percent of economies, respectively. Like UB, ALMP are also closely linked to income level. However, a much higher percentage of lower-income countries have ALMP compared to UB (Figure 2). Across regions, OECD high-income economies utilize ALMP the most, followed by SAR and ECA. In all regions, PES are more commonly used than national skills fund and incentives for training.

Figure 2. ALMP: PES, national training fund, and incentives for training in 2020 (%)

Source: World Bank Group.

Note: Total sample size is 157. See Table A6 in the appendix Ulku and Georgieva (2022) for the sample size of each category.

The paper also provides an econometric analysis of the linkages of UB and ALMP with labor market outcomes across different income groups. Theoretically, both UB and ALMP increase formal employment and productivity and decrease unemployment. In particular, UB compensate for part of the lost income of unemployed individuals and allow them to focus on job search, while ALMP offer counseling, training, and job matching services, among others, to help them find a job. However, due to their unintended effects, such as moral hazard, substitution, and displacement effects, as well as dead weight loss, their overall impact on labor market outcomes will depend on which of these effects are dominant (Calmfors 1995; Card et al. 2007; Van Doornik et al. 2018). Therefore, the econometric analysis hypothesizes that UB and ALMP are positively associated with employment and productivity and negatively associated with unemployment, assuming that their positive effects are stronger than their unintended negative effects .

The findings show that productivity growth has a positive relationship with both UB and ALMP in upper-middle-income countries and with ALMP in low- and lower-middle-income countries, but it has a negative relationship with both UB and ALMP in high-income countries. The findings also indicate a consistent negative association of ALMP with the self-employment rate in all income groups. Moreover, although ALMP and UB have largely insignificant associations with the aggregate employment rate, in upper-middle-income countries, having a longer UB period and training incentives are negatively associated with it.

Given the scarcity of data on labor market policies in developing countries, the new data offer useful information for researchers and policymakers. The result of the econometric analysis showing a positive association of ALMP and/or UB with productivity growth in developing countries is particularly interesting and provides a base for researchers to conduct a deeper analysis .

Join the Conversation