Huimin county is a historical place. This is where Sun Tzu, China’s famous military strategist, was born some 2,500 years ago. Close to the Yellow River Delta, the county has rich soils and a proud agricultural tradition. Until around a decade ago, family farming was the county’s main economic activity. But this is now changing thanks to a combination of new technologies and government policy.

Huimin county is home to 20 so-called Taobao villages: villages where at least 100 e-commerce merchants have set up shop with online sales of at least 10 million yuan (US$1.4 million) per year, selling consumer goods, agricultural inputs and light consumer goods to farmers and offering fresh farm produce to discerning buyers in China’s urban areas. These Taobao villages have exploded in the past decade along China’s eastern coastline, multiplying from just a handful in 2009 when e-commerce giant Alibaba first came up with the idea, to over 4,000 today. To mark 10 years of the Taobao movement, Alibaba held their annual Taobao Village Forum in Huimin county, which we visited to learn more about the role of e-commerce in rural development.

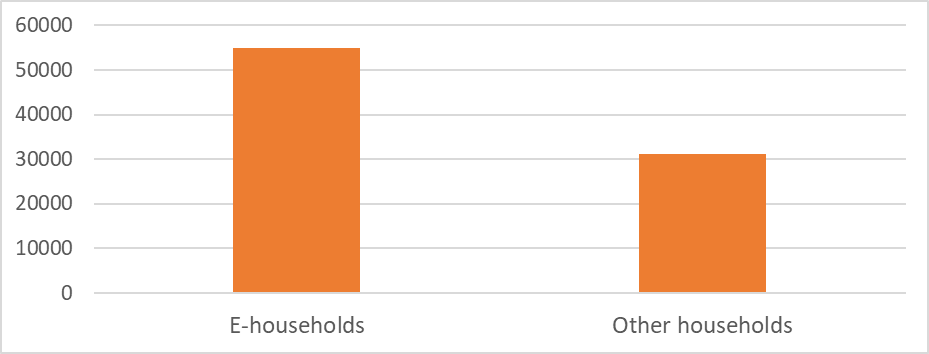

We came equipped with fresh insights from our in-house research on E-Commerce Participation and Household Income Growth in Taobao Villages. Using a unique dataset of Taobao villages provided by Alibaba and a parallel household survey carried out in 2018 in collaboration with Peking University, a forthcoming joint study by the World Bank and the Alibaba Group shows that rural households trading goods on the Taobao platform are significantly better off than those off-grid (Figure 1), and their incomes have increased more rapidly. Participation in e-commerce is not random: those with a better education and with previous work experience outside farming are more likely to bring the entrepreneurial skills needed to reap the benefits of e-commerce. With often flexible work schedules, e-commerce allows women pursue jobs in their hometowns while also caring for children and the elderly as needed. And younger workers are more likely to open online businesses thanks to their IT skills and willingness to seize new business opportunities.

Figure 1: Household income per capita in Taobao Villages in 2017 (RMB)

Source: The World Bank and Alibaba Group (forthcoming)

The potential benefits of e-commerce have been highlighted in past research, including for instance the World Bank’s 2016 World Development Report 2016: Digital Dividends. Nonetheless, despite the powerful association between e-commerce participation and household welfare we found in our research with Alibaba, we don’t really know whether e-commerce was the source of these improvements. This is because a lot of other things have also improved during the same period: the roads have gotten better thereby facilitating commerce in rural areas, the government’s anti-poverty efforts have injected a lot of money into rural communities to support the creation of jobs, and China’s economy overall has continued to grow rapidly. When many things change at the same time, it can be difficult for researchers to isolate the effect of one particular factor such as e-commerce.

In the face of these challenges, our field visit yielded some additional insights. What did we observe? First, Huimin’s offers on Taobao are surprisingly specialized in net-making, building on a long-standing tradition. Historically, Huimin nets were made by hand, using plants or leather strips to make string. Today, the county has various netmaking factories producing everything in the net world from security nets on buildings sites to soccer goals and garden decorations. Huimin’s net ecosystem has received a boost from e-commerce but the cluster existed before. E-commerce provided access to the national market, allowing all producers to grow in scale and encouraging newcomers to enter. The local government supports the cluster with an exhibition hall, and with an e-commerce center where local producers can record live ads and receive marketing support. The close connection between entrepreneurs and the local government echoes China’s experience with township and village enterprises some 30 years ago. Clusters of specialized villages have sprung up around the country – sometimes building on old traditions such as net string as in Huimin, sometimes starting a new business line from scratch such as furniture making in Suining (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Taobao village clusters – a new wave of township and village enterprises?

In Huimin, Mr. Zhai, Guolong’s company still produces hand-woven nets, employing up to 100 women from the local village in his three-story factory, which is also his home. Mr. Zhai tried his hand at various trades before, in 2013, he had the idea of posting a photograph of a hand-woven net on the Taobao platform. With this his business success began. Last year, the online sales from his shop reached 8 million yuan (US$1.1 million). His nets are tailor-made to customer specifications. Three young women take in orders online and pass them on to a group of older women who weave nets on the factory floor downstairs. Their grandchildren play among the rolls of string. Mr. Zhai’s business is booming. He employs three shifts of weavers, although his workers can come in and out depending on their family needs. This is a second characteristic of the Taobao villages: by bringing employment opportunities to rural communities, e-commerce both attracts migrant workers back and integrates the elderly and women no longer employed in agriculture. Higher labor force participation rates may be one reason e-commerce households are better off.

We have a third observation: Huimin county has not only seen the rapid development of non-agricultural jobs. Agriculture in Huimin has also been changing rapidly. The local government is promoting land consolidation to make room for larger, more efficient and ultimately more ecologically sustainable farms. Just outside the nearby city of Binzhou is the Xincheng farm of Mr. Zhao, Wenxin. He purchased it in 2013 and has since invested in organic fruit, cut flowers, and tree seedlings. All his products are certified to European Union standards for food safety, earning him high prices and pointing the way to less polluting, safer and more efficient agriculture. Mr. Zhao also runs a water park and offers rural retreats on his land – service industries where margins are higher than in agriculture, he says. Mr. Zhang provides employment to more than 1,000 workers, mostly former family farmers, who complement the income received from the transfer of their land with wages up to 20,000 yuan per year (close to US$3,000).

For those unable to continue farm work, a combination of government support and e-commerce opens new opportunities. The Poverty Alleviation Industry Park in Huimin county produces high-end mushrooms grown in greenhouses in specially prepared fiber rolls. The mushrooms are hand-picked and sorted by retired farm workers. The park has received a government grant under the poverty alleviation program to employ farmers from poor households. It also provides flexible jobs to “mushroom grannies” – ladies in their 70s and 80s sorting mushrooms to complement their meager pension income. In a room next door, the park offers after-school activities to children in the village – especially those whose families work at the park – who are looked after by the grandmothers. The grannies supplement their meager rural pension, the children get quality after-school care, and the mushroom factory sells its high-end product through e-commerce to customers all over China.

Figure 3 Mushroom grannies and children at daycare

From this visit to Huimin, it is clear that e-commerce has brought new opportunities to China’s countryside. It has catalyzed local entrepreneurship, brought some migrants back home, reuniting families and improving the social fabric of the village. It has done so particularly in China’s coastal provinces, benefiting from excellent infrastructure and proximity to booming consumer markets. And it has built on and benefited from the substantial transfer of resources by China’s government to rural areas over the past decade. These circumstances may not be easy to replicate elsewhere. Still, it is clear that in China’s poverty reduction story, one chapter should be devoted to e-commerce and the Taobao movement. With more and better data, we hope to be able to dissect the relative contribution of e-commerce and its “analog complements,” so that other countries can learn how to harness the digital revolution for the development of their rural communities.

Join the Conversation