Photo: Fauzan Ijazah/World Bank

Photo: Fauzan Ijazah/World Bank

The Indonesian government has achieved its aspiration to transition from a low-income to a middle-income country. Impressive development progress to date has allowed Indonesia to effectively address its 2024 goal to eradicate extreme poverty. Poverty-reduction has been broad-based, with growth in the Indonesian economy remarkably inclusive, but a third of households remain susceptible to falling into poverty upon a shock. Levels of inequality have also decreased across the country, though rural regions in Nusa Tenggara and Maluku Papua remain behind especially in human capital outcomes.

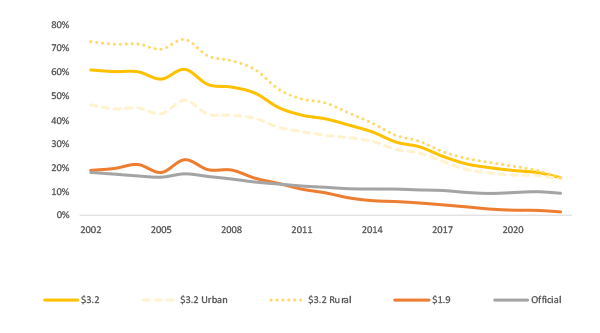

The decline in Indonesian poverty from 2002 to 2022, using absolute poverty lines of USD$1.90 per day and USD$3.20 a day

The World Bank’s Indonesia Poverty Assessment: Pathways Towards Economic Security takes a close look at the trends in poverty and equity, and suggests how Indonesia can sustain and accelerate poverty reduction for a larger segment of the population – in better alignment with its aspiration to become a high-income country in 2045. The report highlights the need for Indonesia to broaden its definition of poverty, as extreme poverty measured at US$1.90 2011 Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) fell to 1.5 percent in 2022. A move to US$3.20 a day would change not only the number of the poor, but also their profiles, for example by including more workers outside agriculture. Poverty would also be more transient. Accordingly, policies would need to be broadened from fine targeting of the extreme poor towards inclusive growth strategies to allow poor households reach economic security. A multi-pronged approach based on three complementary pathways would help meeting this new ambition: creating better opportunities, protecting against poverty, and financing pro-poor investments.

Creating Better Opportunities

The most sustainable way to escape poverty is work. With an unemployment rate of 5.9 percent in 2022, most Indonesians have some kind of work. Even among the poor and economically insecure households, more than 8 in 10 have work. However, they still do not earn enough to escape poverty – and are unable to reach economic security. In rural areas, every second poor household relies on agriculture as the main source of livelihood. However, income from agriculture alone is insufficient to escape poverty. In both urban and rural areas, many households also have work in services. While the service sector can provide productive work, many workers are trapped in low-value-add services with insufficient incomes.

The challenge of low productivity can be tackled from multiple sides. Agricultural productivity can be increased through improved agricultural extension services and market access. Removing agricultural subsidies focused on food production can encourage farming of cash crops, often better suited for some soil conditions. Competitiveness policies, including less restrictive trade and foreign direct investment policies, can foster job growth more generally. Similarly, digitalization can provide opportunities but requires digital skills, connectivity, and a supportive policy environment. At the same time, workers need to be equipped with the right skill mix to prepare for new jobs – not only digital skills but more generally right skills for the right job. Policies could, for example, increase the level and quality of secondary and especially tertiary education and invest in technical and vocational trainings.

Protecting against Poverty

Indonesia is vulnerable to shocks brought about by global realities. One-third of the Indonesian population remains economically insecure. Climate-related events alone have accounted for approximately 70 percent of the disasters in Indonesia in the decades between 1990 and 2021. With more than 300 natural disasters recorded, upwards of 11 million people have been impacted. It is therefore increasingly important for Indonesian policymakers to prioritize investments in resilient infrastructure to mitigate the impacts from these inevitable shocks.

However, shocks will always happen – and their impact cannot be fully mitigated by resilience investments. Without sufficient access to social safety nets, the poor and economically insecure segments of the population will continue to shoulder the brunt of the disaster burden – climate-related and otherwise. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of the existing social protection system in Indonesia, but also pointed to the need to do more, especially with respect to targeting and adequacy of benefits. In addition, financial inclusion could be prioritized to provide better access to saving devices and loans, for example. This can give households another tool to buffer the impact of shocks.

Financing Pro-Poor Investments

Policies recommended in the first two pathways will not only require political will, but resources too. These resources are not impossible to come by. The Poverty Assessment uncovers avenues to raise finance for pro-poor investments. For example, a re-examination of subsidies for energy and in agriculture could assist in raising revenues, as could a re-assessment of the use of VAT exceptions. Increased taxes on alcohol, tobacco, sugar and carbon could also raise funds for pro-poor investments.

In addition, increased capacity within sub-national government, especially in the administration of expenditures, can help improve the quality of public services, particularly in education and health. This is particularly important in the context of lagging remote regions – with lowest capacity – suffering from particularly low human capital outcomes. Investments in better capacity can, thus, also help reduce inequality across Indonesia.

Conclusion

A carefully designed set of policies embedded in a multi-pronged approach can help sustain Indonesia’s success story in extreme poverty reduction. It would help Indonesian households reach economic security, such that shocks cannot reverse achieved gains in reducing poverty, in line with Indonesia’s aspiration to reach a high-income country status.

Join the Conversation