Stories away from school

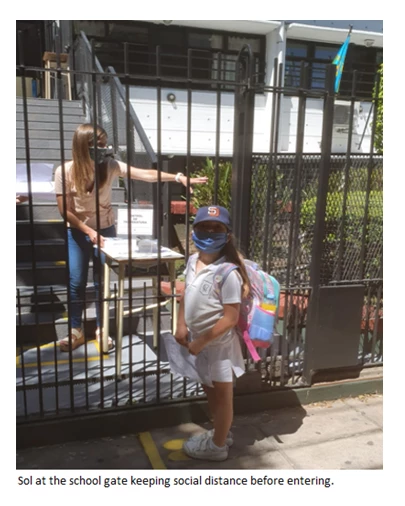

“Is this true? Am I returning to school?”, Sol asked in disbelief when her parents told her that her primary school in Argentina will open for the first time in 15 long months. Sol had finished kindergarten virtually the previous year and, by now, had gotten used to attending classes from her parents’ laptop. However, starting 1st grade had not been easy, as Sol had a different teacher. On Wednesday, June 11, 2021, when a mask-wearing Sol got to the point of knowing her teacher Julieta in person for the first time, she barely recognized her. Julieta was also wearing a mask and looked taller than Sol foresaw. “Are you Julieta, my teacher?”, Sol asked, genuinely and gracefully, to the (not visible) tender smile she generated in her interlocutor. And this is where a new (in-person) school story for Sol began.

Within countries, vulnerable groups and students living in rural areas were disproportionately affected. Ecuador’s 13-year-old Margarita, lives in the rural community of Pimanpiro and can’t wait to return to school after being completely disconnected due to the lack of Internet in the village. A bit luckier were Peru’s 15-year-old Medaly or Bolivia’s 14-year-old Luis, who were able to avail of distance learning thanks to some access to digital devices, but faced different hurdles. While Luis had access to Internet and to an old monitor where he could “watch classes” better, his computer would shut off if he turned on his video. Medaly, on the other hand, could only “connect to classes” using her mom’s cell phone, which had limited and costly-to-expand data access.

The catastrophic effects of school closures in LAC

Stories like the ones depicted above help understand the degree of disruption generated by the pandemic in the education systems in LAC. The COVID-19 outbreak not only deepened inequities in the most unequal region in the world, but generated new ones. Within the context of the experience in one of the longest-closed school systems in LAC, Argentina, Romero et al. (2021) coined one of these new segregation patterns as the new reality of “Zoom” versus “Whatsapp” schools.

According to recently updated regional simulations, the number of learning-adjusted years of schooling (LAYS) lost due to the pandemic, is expected to be between 1.1 and 1.4 years, taking away from an already low regional average of around 7 years of education per child. And the proportion of adolescents not able to adequately understand and interpret a text of moderate length (using PISA test scores to assess 15-year-old below minimum proficiency levels) could have increased from about 50% up to a dramatic 70% or more. Even just assuming a 10-month school closure, already clearly exceeded in most countries, the projected annual earnings of the average LAC student at school today would decline by about 10% during his/her lifetime: a stark impact on living standards.

Beyond simulations, at least 20 different systematic reviews of the impact of school closures on student achievement, published from evidence collected all over the world, point to significant losses, with emerging evidence on the LAC region pointing to a generational catastrophe, with the most vulnerable student groups disproportionally affected. The new 2019 data on the 4th Comparative and Explanatory Regional Study (ERCE, from its Spanish acronym) to be released today by UNESCO’s Latin American Laboratory for Education Quality Assessment (LLECE, from its Spanish acronym) will help provide an updated learning outcome baseline for the region to get a better grasp of the learning losses.

But let’s focus on the positive: after more than an academic year of education systems largely closed, schools across the region started, slowly but steadily, to reopen. Such processes have not gone without hiccups, remain highly fluid and have been implemented with various levels of readiness. Notwithstanding these challenges, if there is one area of agreement across every single education stakeholder after COVID-19 is that in-person education cannot be substituted by anything else.

Reopening schools in LAC: The urgency of the return to schooling and learning

Second, and arguably even tougher, is the learning recovery challenge. According to a recent study on remote learning in secondary education for the Brazilian State of São Paulo students only learned 27.5 percent of the in-person equivalent under remote learning. Recovering learning will need a comprehensive accelerating learning recovery strategy, building on remedial programs to help support students to recover critical literacy and numeracy skills (e.g. teaching-at-the-right-level programs; individualized self-learning programs; small-group tutoring programs; instruction time expansion programs). It will be critical to start systematically collect evidence on what has been working in the region and beyond, prioritizing cost-effective programs that can have strong impacts at scale. In-classroom learning assessments, especially formative ones, could help diagnose the depth, breadth, and characteristics of learning losses. Teachers and principals will need to be supported throughout this period, with civil society organizations playing a critical role. This dual schooling and learning challenge will be explored and supported through a joint partnership between the WBG and the Inter-American Dialogue (IAD). The “Returning to Schooling and Learning after COVID-19” series will be launched on December 14.

LAC’s education systems have a very steep curve ahead of them. Recovering from the “educational earthquake” engendered by the pandemic will certainly be an uphill battle. However, in the midst of the anxiety and angst that this situation generates around the future of LAC generations, lays a unique opportunity: that of building back better. The time to protect and enhance education budgets for equity and efficiency, to revamp early childhood education and improve youth’s skills sets for longer-term challenges, and to carry out effective educational policies for sustainability is also now. The Sols, Margaritas, Medalys, and Luises of LAC are still recovering from their traumatic experiences in the past 18 months, and still looking for responses. Let’s protect their human capital. Time to act is now.

Join the Conversation