Garoto em um pátio de escola

Garoto em um pátio de escola

Sofia’s parents have saved enough to send her to secondary school in a poor neighborhood of Asuncion, the capital of Paraguay. Sofia, who started the year with some skills gaps, was finally making great strides thanks to additional teacher support. Early March, however, everything changed with her school closing. Some limited distance education was offered, but Sofia’s home does not have internet connectivity, so she was not able to take advantage of this option. TV and radio education have helped but have not offered the same content or teacher support that her school did until March. Struggling to remain engaged, Sofia is now thinking of dropping-out and looking for work to help her family.

At the start of the pandemic, many children and youth in the region, particularly the most disadvantaged, were still facing serious educational challenges. While enrollment continued to increase over the last decades and learning outcomes were on an overall slow positive trend, about 50% of children could not yet read with proficiency by the late primary age, and, on average, 15-year-old students were three years behind in reading, mathematics, and science when compared to their peers in the OECD countries. This learning crisis was even starker for the most disadvantaged students: gaps between the top and bottom quintiles in secondary education PISA scores were the norm in most countries of the region, and equivalent to at least 3 schooling years. The recently launched 2020 Human Capital Index, computed before the crisis, shows that Latin American youth were only 56% as productive as they could be if they had full health and education.

The education costs of the pandemic

Six months into the pandemic, countries have had to make formidable efforts to mitigate the potentially dramatic consequences of school closings on their children and youth, by setting-up distance education options. A formidable challenge in a context where less than 60% of individuals use internet in the region. Most countries have raised to the challenge and moved rapidly and creatively to use education technology to deliver remote-learning solutions, in some cases, like Uruguay, Mexico, Brazil and Chile, building on pre-existing investments and efforts, in other cases, by stepping-up and learning from others. Knowledge sharing, actively supported by the World Bank, has been tremendous leading to the implementation of increasingly multi-modal solutions, where traditional means such as TV, radio and printed materials, complement internet-based solutions, to make remote learning more inclusive. World Bank education projects have been adapted to support content for distance schooling, ICT solutions, and multi-modal delivery and support, including innovative strategies, such as the use of SMS and WhatsApp helplines, to engage teachers and parents.

However, recent evidence in some countries painfully reminds us that distance learning cannot replace face-to-face learning, even more so for the most vulnerable. Even assuming coverage is in principle secured thanks to multi-modal strategies, and support strategies are in place, participation and engagement are difficult to achieve. A study by the Foundation Lemann shows that, while 92% of students are participating in remote learning activities in the south region of Brazil, only 52% of students are doing so in the, poorest, north-west region. And even if take-up is good, the continuity and quality of the teaching and learning process pose significant challenges, especially for the most vulnerable children and youth with much less family support and access to complementary digital devices. Even in a country like Chile, where many schools are able to offer distance learning, a recent study, jointly developed with the World Bank, shows that, when taking into account coverage and effectiveness indicators, distance education would only be able to mitigate between 30 and 12% of learning losses associated with school closings, depending on the duration of the school closing (6 or 10 months). Importantly, effectiveness decreases to a low of between 18 and 6% for public schools, where the most disadvantaged students are enrolled.

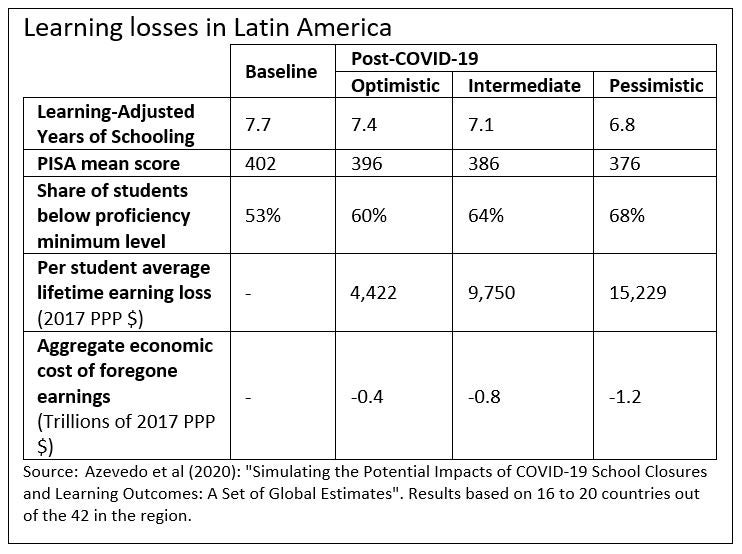

As a result, the region is on a path to experience significant learning losses potentially jeopardizing the education outcomes of an entire generation of students. Initial simulations undertaken by the World Bank, under different school closing scenarios and assumptions on the effectiveness of distance education, reveal stark prospects. The region’s Learning-Adjusted Years of Schooling (LAYS, a metric that combines the amount of schooling that children typically reach with the quality of learning during school years, relative to some benchmark) could drop by almost one year if schools stay closed for 7 months, and by half a year if schools stay closed for 5 months. Additionally, the share of students below minimum proficiency levels on PISA scores would increase from 53% to respectively 68% and 64%.

These are grave projections especially if we consider that most countries are already well on their way to 5 months and some are already going for 7 months of closures. Worryingly, according to the latest UNESCO-UNICEF-World Bank survey, countries in Latin America are the most reluctant to reopen nationwide: less than 30% would do it compared to 40% or more in the rest of the world. While this may be a legitimate reflection of the severity of the pandemic in the region, can this also be a sign of limited readiness to re-open?

These results are still an under-estimation of the true cost of the pandemic, especially for the most vulnerable children and youth. The average hides huge disparities within countries, with children and youth from the most disadvantaged backgrounds suffering the most for multiple reasons related to access to distance education, parental support and economic hardship, among others. According to the same study on Chile, students from the lowest income quintile could lose up to 95% of their yearly learning. Recent results published on Costa Rica show that the poorest students could be losing almost an additional year of schooling vs. the richest.

Still, these results do not yet capture many other negative effects of the crisis. Many students, particularly from lower-income groups, will disengage themselves and simply drop-out of school. A recent World Bank policy note on Colombia shows that school closures could lead to between 53,000 and 76,000 students dropping out of school by December 2020. The country is actively pursuing strategies to counter these effects. Staying at home is also affecting students’ mental health, as well as their vulnerability to risky behaviors. This is especially the case for children from the most vulnerable households who are experiencing a completely different learning experience at home than children from wealthier backgrounds. In the medium and longer-term, and with the economic crisis hitting the region very hard, countries may suffer significant losses in human capital and productivity. It is expected that learning losses may translate into an aggregate economic cost of foregone earnings of between 0.8 and 1.2 trillion US$ lost (in 2017 PPPs).

Getting ready now to get children and youth back to school

These huge costs can be mitigated if governments act NOW to continue improving the effectiveness of distance schooling and make sure schools are ready to reopen. Continuing to improve the reach, take-up and quality of remote learning is essential. Multi-modal delivery, with explicit strategies to reach out to the most disadvantaged groups, parental and teacher engagement with interactive communication, prioritization of the curriculum, and learning evaluation strategies are emerging critical drivers of effectiveness according to an on-going review of the World Bank. But even with the best efforts, remote learning cannot replace face-to-face learning.

Reopening schools is an excruciating decision which needs to be informed by public health data. While timing cannot be entirely controlled for, what governments can and should do now is investing in school readiness for safe and effective reopening. Several organizations, including the World Bank, have teamed up to provide guidance on key readiness criteria for reopening and start extracting lessons on what works. Among the emerging lessons, what stands out is that with sufficient capacity and resources, schools can successfully implement context-appropriate health and hygiene protocols, and that early and regular communication and support to teachers, parents, and students can help address concerns, surface innovations, and ensure a safe, widely accepted reopening.

Reopening effectively will also entail important management and pedagogical decisions, including systemic and targeted measures to ensure that schools teach at the right (post-COVID-19) level. Simplifying the curriculum and adapting the academic calendar year have shown to be working to facilitate learning recovery, and so have remediation programs and supporting teachers and principals to implement them, also in a blended (face-to-face/remote) learning setting, which may become the new normal. Schools need to be prepared to re-start with flexibility as soon as possible. A focus on socio-emotional skills and child and families’ well-being, and strategies to prevent dropouts of youth at-risk, will also be critical. Education projects and technical assistance supported by the World Bank in several countries of the region are already striving to support safe and effective school reopening, building on these lessons. A smart use of technology, with clear guidance, development of capacities and effective monitoring, is at the core of the engagement.

Preparing for safe and effective reopening will require governments to invest the necessary resources now, provide additional education funding to schools and communities hit the hardest and explore the potential for using resources more efficiently. A smart use of technology and well thought through teacher allocation and curricular reforms may provide opportunities for higher efficiency, while laying the ground for longer-term improvements in education systems. Governments of Latin America need to consider the looming education crisis for what it is: a once in a lifetime generational crisis which will affect the education outcomes, human capital and productivity of an entire generation of children and youth. There is no time to lose to take further action and keep Sofia’s dream of completing her secondary education successfully.

Join the Conversation