Cредняя школа имени Раиньи дон Леоноры, Лиссабон

Cредняя школа имени Раиньи дон Леоноры, Лиссабон

From a very early age, modern children spend more and more time in nurseries, kindergartens, or schools. According to international statistics, the coverage of educational services is increasing worldwide. In 2015, 49% of children were in pre-school institutions, more than 89% of children attended primary schools, and 65% had access to general education. According to the OECD, students are spending 7,538 hours in the school premises on average by the age of 15[1]. Thus, school build environment becomes the second place where students spend the majority of their time, after home. It also becomes a third teacher if it is arranged to support learning. The term third teacher was first used by Italian pedagogue Loris Malaguzzi. He claimed that the learning environment can become a third teacher after the family and the pedagogue, representing not only a tool for educators but also independently providing a source for discoveries and experiences (Cagliari et al. 2016).

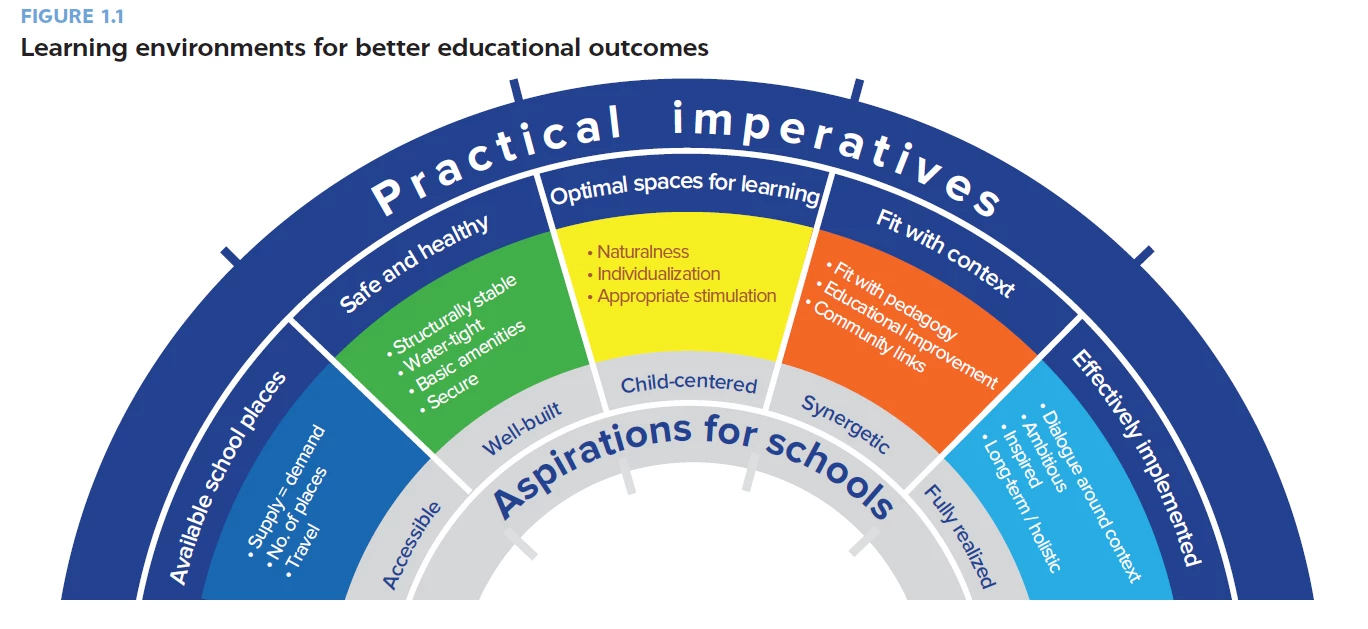

The growing education coverage raises more concerns about the quality of education in terms of curricula, teachers’ qualification, and availability of proper facilities. One of the ways to ensure the education quality, is to create or improve the education facilities so that they are child-centered and provide a safe, inclusive and effective learning environment for all.

How do we achieve it in practice? Building a school requires knowledge about pedagogy, teaching approaches, construction technologies, site parameters, and users needs, as well as strong involvement of different stakeholders (project managers, school principals, architects, politicians, community members). For those who develop and implement the national policies on school network expansion and those who work on the education facilities project implementation in the field, the availability of the research data in these knowledge areas is crucially important for taking the informed decisions.

The research on the impact of learning environments and education facilities design is building up. Our new book The Impact of School Infrastructure on Learning: A Synthesis of the Evidence reviews the current research on learning environments and focuses on how school facilities can affect children’s learning outcomes. We identify key parameters that can inform the design, implementation, and supervision of future educational infrastructure projects. We reflect on aspects for which the evidence could be strengthened and identify areas for further exploratory work.

The following parameters of school settings might significantly impact the academic outcomes of children: school size, access to school and time spent traveling to school, class size, schedule and length of the study day, optimal use of learning environments and availability of school for the children with special educational needs.

The engineering aspect of new and renovated buildings also contributes to the overall quality of the learning environment – such parameters as natural light, temperature, and quality of air are significant contributors to the perception of the space and ability to function. The one of the most influential study - “Clever classrooms” by Prof. Peter Barrett (one of the principal authors of the report) - claims that the learning environment explains 16% difference in achievement, and half of the improvement in learning outcomes is related to hard infrastructure solutions (quality of air, lightning, and temperature).

The most successful design is the one that serves pedagogy the best. It is possible when users of the building and stakeholders plan and develop the design in conjunction with their cultural, pedagogical, and economic contexts. Sometimes schools or preschools become part of community centers, where for example sports facilities can be used by neighbors, while students may use the public library.

New learning approaches require both - different skills from teachers as well as different learning environments. For instance, today, the education community is actively discussing a very new curriculum reform in Finland. Its principal difference is the introduction of phenomena-based lessons where subjects are becoming instrumental in multidisciplinary research activities. It means that the class is no longer a gathering of a certain number of students for a 40-minute lesson, but the parallel work of diverse groups of students and teachers on a given topic. For example, at the same time, two small groups may work with two teachers, and one larger group may work with one teacher. Experimentation, collaboration, and creativity are becoming very important for teachers in such settings.

Different approaches to design may achieve better economic characteristics of the building while making areas more diverse and multifunctional. Where traditional school allocates 10 - 25 percent of the space to the corridors the alternative approaches like central space design may ensure the use of this space while at the same time reducing the footprint by 10-15%. We need to mention though that the fit for purpose is important for learning environments and teaching and learning practices should be the leading factor in the learning environments arrangements.

There is a growing need for strengthening the exchange on best practices between the World Bank’s project teams and our clients. We also see the need for further analysis of the evidence on the relationship between learning environments and learning outcomes.

[1] Source: OECD (2017), “Table D1.1. Instruction time in compulsory general education1 (2017)?”, in Education at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing

Join the Conversation