After getting off to a slower start than our colleagues in health, results-based financing (RBF) is gaining much momentum in education.

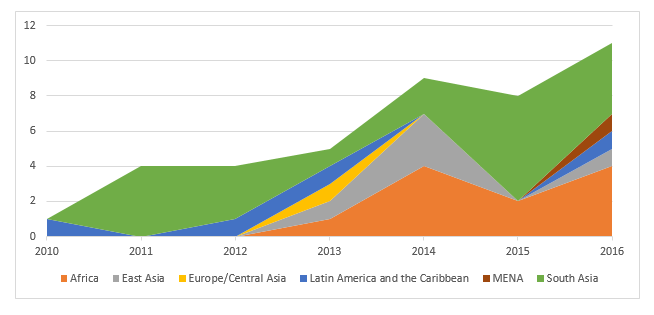

Use of the Program-for-Results Financing (PforR) instrument is still pretty limited. However, we do have a wealth of experience with implementing Investment Project Financing’s (IPF) using Disbursement-Linked Indicators (DLI), particularly in South Asia (see Figure 1).

Several years in, it’s time to start documenting what we’re learning, with the view of informing the next round of DLI operations. This is especially important in light of the projected increase in our RBF portfolio, as we work to respond to growing client demand, and to meet President Kim’s Incheon pledge to double our RBF portfolio to $5 billion by 2020.

Figure 1. Number of Results-based financing projects in Education, by Region

Among the theories, hypotheses, rumors, and myths that one might hear about RBF, here are three that we wanted to explore:

- Does linking disbursements to results put undue pressure on teams?

- Is it truly the money that serves to motivate?

- How many DLI’s should projects have? How many is too many?

During a recent supervision mission, we interviewed counterparts in the ministries of finance, education, health, and the Early Childhood Commission. We also spoke with colleagues in teams tasked with implementing and providing additional financing to the operation.

Through those discussions, we learned the following lessons:

Disbursements flowed predictably. The DLIs were largely met on time. In the few instances when they slipped into future years, they were offset by other DLIs that were met ahead of schedule. Never did the World Bank team find itself being pressured to disburse. The DLIs provided a strong incentive in the crucial early stages of strategy implementation, and achieving them created momentum.

The amount of money doesn’t really matter. There’s a view that one of the theories of change behind results-based financing relates to dangling money in order to shift government priorities (aka pecuniary interests). In this case, however, the DLIs weighed in at just $180,000 each. As such, the money per se doesn’t represent the incentive; but the increased attention to the results sought, and the forced coordination of a unifying results framework, makes us all focus on what actually matters.

An abundance of indicators (45!) isn’t too many. In addition to having 45 DLIs, the project had an additional 30 monitoring indicators. We figured this would be deemed as excessive. Surprisingly, however, given the numerous implementing agencies involved, and the need for a holistic cross-sectoral view of what needed to happen when and by whom, this complete monitoring table was universally appreciated.

The original 45 indicators meant meeting nine targets per year for five years; 12 more indicators were added in 2014, as part of an additional financing. The spacing of these indicators was also appreciated, as it ensured that momentum in implementation never let up.

These are a few surprise findings from our initial exploration. To be sure, there are also some practical lessons that the team has learned, such as the importance of balancing sectoral involvement and consulting widely early on in the preparation process.

While this is also true for non-DLI projects, it is particularly important for cross-sectoral DLI projects because reaching those early target indicators (for those early disbursements!) is important to set a good implementation pace. This requires entities that do not normally work together to suddenly communicate, cooperate and learn to trust each other in the earliest of stages. The more practice that new partners from various ministries have to work together upfront, the less time is spent during implementation for consensus, ownership, and relationship building – which can go a long way to jump start implementation.

For now, we’re focusing on how to develop and define good DLIs. In the coming year, we plan to continue to explore and extract lessons of DLI operations and see how they have fared as compared to traditional input-based financing models. We’ll also be surveying project leaders on the dos and don’ts of DLIs. So do watch this space and please be in touch if there are directions you’d like to point us to.

Harriet Nannyonjo and Melissa Adelman contributed to this blog post.

Find out more about the World Bank Group’s work on education on Twitter and Flipboard .

Read about Results Based Financing in education.

Join the Conversation