The popular image of the out-of-school, out-of-work youth of Latin America is not generally a positive one. For one thing, the term used to label them – “ninis” – defines them in the negative. It comes from “ ni estudian ni trabajan”, the Spanish phrase for those who "neither study nor work.”

And then there’s the way they’re portrayed. At best, the ninis are derided as ne'er-do-wells who spend their time playing video games or watching TV and drinking, instead of educating themselves or building careers. At worst, in violent settings, ninis are conflated with the foot soldiers of the drug cartels. As a result, these youth are viewed not with derision but with fear. A recent Factiva analysis of the terms most linked with “ninis” in the Mexican media found that the top 10 included “violencia” (violence), “flojo” (lazy), “drogas” (drugs), and “inseguridad” (insecurity).

The problem of the ninis has received more attention over the past decade, despite the rapid growth and development that the region has mostly enjoyed. Is this because the problem is really growing, or is it just because we now have a catchy label to apply to these youth? Either way, what can the governments in the region do to integrate these youth more fully into society—and how can the World Bank help?

To answer these questions, the Bank carried out a three-year research program that culminated in Out of School and Out of Work: Risk and Opportunities for Latin America’s Ninis (co-authored by Rafael de Hoyos and Miguel Székely, and also available in Spanish) published by the Latin America and the Caribbean region’s Chief Economist’s office.

What did we learn?

- There is too little progress: One in five youth aged 15–24 in Latin America is out-of-school and not working. While the share of youth who are ninis has declined gradually since 1992, it hasn’t fallen fast enough to offset the growth in population. As a result, the number of ninis in the region has grown by two million to 20 million.

- Most ninis are women: The typical nini is not the shiftless or criminal male pictured in the media. Instead, it is a young urban woman without a secondary diploma. Women account for two thirds of the region’s nini population. They become ninis, most of the time, because of an early marriage, teen pregnancy, or both.

- But there is a growing “masculinization” of the problem: The number of male ninis is growing. In fact, young men account entirely for the increase of ninis in the region. As young women have gotten more access to education and employment since 1992, the number of male ninis shot up by 46%. This surge may explain the media’s male-oriented depiction of the ninis.

- Most male ninis drop out for jobs: Most young male ninis originally dropped out of secondary school not primarily to play video games or watch TV, but to earn money. Yet the low-skilled jobs they get are unstable, so any economic shock lands them back in unemployment—and with virtually no chance of returning to school.

- Do ninis contribute to crime and violence? Given this dynamic, it’s not surprising that in high-crime and violent contexts, there is a strong association between the number of ninis and the rate of homicides. In high-crime states of Mexico in the violent 2007-12 period, the rise in ninis statistically explains at least a quarter of the increase in homicides. In parts of the region, male ninis are trapped in a vicious cycle. They are drawn into the violent illicit drug trade by a lack of job opportunities, and as a result they contribute to the unstable conditions that deter firms from investing and creating new opportunities. In contrast, in lower-crime contexts, there is no statistical association between ninis and crime.

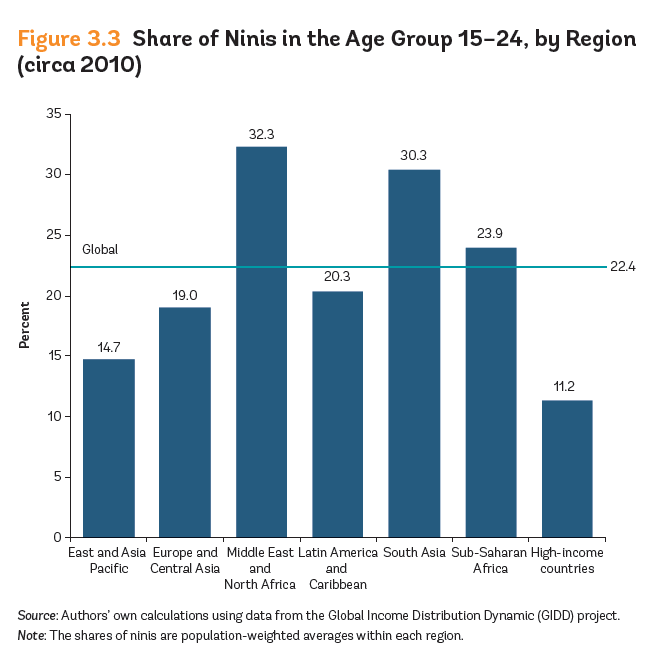

- Ninis are a global problem: Finally, the problem is not unique to Latin America. Our research shows that there are 260 million ninis worldwide, with especially high shares in Middle East and North Africa and South Asia regions (see graph below). In fact, the increase in number of Latin America and the Caribbean ninis is slightly lower than in the global average—though far higher than those in the high-income countries.

How can governments tackle the nini problem?

To learn the answer to that question, you’ll have to read or watch beyond this blog post. Our report lays out a variety of evidence-based strategies for both keeping youth in school and finding employment for those who have dropped out. Last week, we launched it at the Woodrow Wilson International Center in Washington DC with Jorge Familiar, the World Bank’s Vice President for Latin America and the Caribbean, OAS General Secretary Luis Almagro, and Enrique Roig of Creative Associates.

To learn more, watch the recording of the event in English or Spanish.

Read the press release and watch a short video about ninis .

Join the Conversation