Online learning was associated with an increase in learning inequality in Korea. Copyright : Shutterstock

Online learning was associated with an increase in learning inequality in Korea. Copyright : Shutterstock

The alarming levels of learning loss from school closures during COVID are higher for poorer countries than for rich ones. The same pattern is true also at the country level—the wealthier do better, the poor fall behind. In EdTech in COVID Korea: Learning with Inequality, we find that there were low levels of learning loss overall, while students in the middle and bottom of the distribution were more vulnerable to the negative effects of school closure.

“I felt I was trapped at the same place and got lots of psychological stress,” Seo-bin Ma, a high school student near Seoul, told CNBC in October 2020. “What was most difficult is that I didn’t have my friends with me so it was hard to be dedicated to my studies.” What do we know about the effects of school closures on student performance during this difficult time?

We were able to compare what happened to middle school students in Seoul before and during the pandemic. We observed student performance data for math, Korean, and English for two separate cohorts of students in 8th and 9th grade. The comparison was made between one cohort that did not experience COVID-related school closures and online learning (2018 to 2019) and a cohort that did experience COVID-related school closures (2019 to 2020).

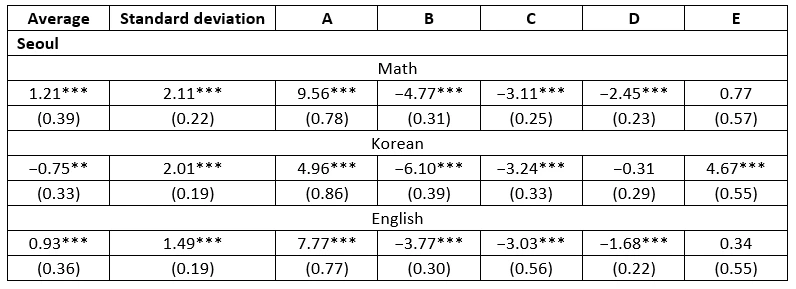

Two main messages stand out from the comparison. First, the average student score increased in math and English and decreased in Korean. Second, learning inequality increased: there was an increase in the proportion of students who performed very well (Grade A), but also an increase in the proportion of students who got the very worst grades (D and E).

Table 1. Estimates of changes in learning associated with COVID school closures

Note: Results for linear regressions. Estimates are for the parameter on the binary variable denoting the COVID-affected cohort in the second period. Standard errors in parenthesis. Asterisks denote statistical significance at the 10 percent (*), 5 percent (**), and 1 percent (***) levels. The estimations for the percentages in categories A–E use seemingly unrelated regressions (SUR).

These results are not unique to Seoul; based on an analysis by the Gyeongsangnam-do Office of Education, test results for middle and high schools in Gyeongsangnam-do show little learning loss during the online and hybrid learning period, but increasing learning inequality. Similarly, an analysis of results of 15.8 percent of 8th grade students nationally by the Seoul Education Research and Information Institute showed modest changes in student performance, specifically a small level of learning loss concentrated among the lower-performing students and some gains in the number of higher performing students during the period of online and hybrid learning due to COVID (2019–2020).

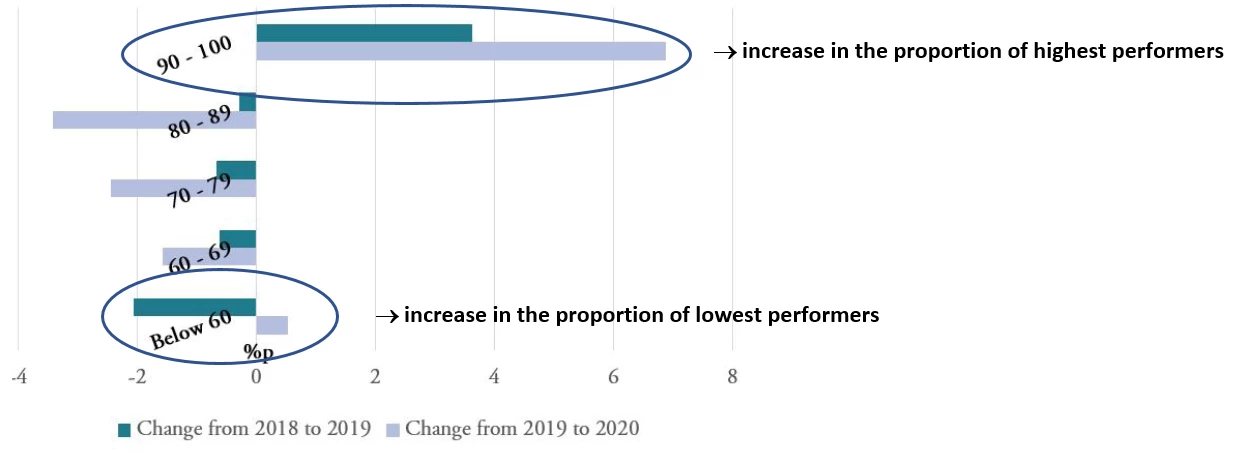

Figure 1. Percentage change in English scores (8th grade versus 9th grade, two school-level cohorts)

Source: Seoul Education Research and Information Institute 2021

Korean media has focused on this increase in “educational polarization” (학력 격차) during the pandemic. This is an important message. However, the polarization or “shrinking middle” pattern has been present in Korea before the pandemic. Since 2000, the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) scores for 15-year-olds show that the number of students achieving the lowest and highest levels has increased while the number of the middle levels has decreased. Rising educational inequality in Korea did not start with COVID, but it appears that hybrid learning has accelerated the trend. The technological “Law of Amplification” implies that whether the effects of technologies are good, bad, or neutral depends on who is using them, how, and in what context. The experience of Korea and other countries suggests that the use of technology without special measures and support for low-performing schools and students is likely to make an inequal system more unequal, faster.

What can other countries learn from the Korean experience?

Korea’s recent experience highlights the possible education system-level resilience supported by EdTech. However, as the data from Korea show, even high-income countries with high performing education systems are susceptible to rising inequality in education outcomes. Just as lower-income and vulnerable students experienced greater levels of learning loss, middle- and low-income countries likely experienced greater levels of learning loss during school closures and distance learning. There are also impacts on health, nutrition, violence, and other key areas of development, overall having large negative impacts on human capital.

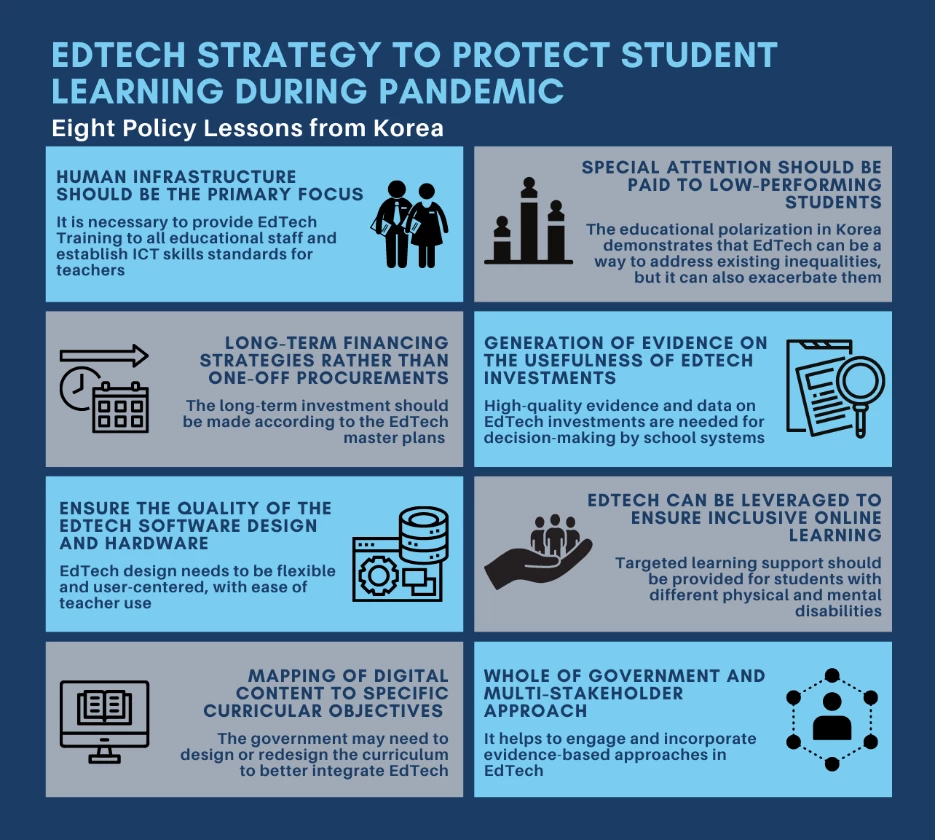

EdTech is likely to become more important with the acceleration of the fourth industrial revolution and an increase in the frequency of school closures due to disasters and emergencies, many linked to a warming climate. While more evidence is needed to be conclusive, it appears Korea suffered low levels of learning loss due to COVID-19 school disruptions, while learning inequality increased. The following are the key elements that could apply in other country settings and additional steps Korea and other countries can take to support student learning and reduce inequality.

Figure 2. Policy lessons from Korea on EdTech strategy to protect student learning

Join the Conversation