[StagLearning:stagˈlərniNG/ noun

A condition of no growth in basic learning outcomes, despite high levels of education spending.]

Argentina is no stranger to stagflation – a condition of stagnant economic growth, despite high inflation. But, over the last decade or so, it has also been suffering from staglearning – no growth in learning, despite high levels of spending on education. This is not just inefficient; this is heartbreaking since it means the country is not capitalizing on potential poverty reduction.

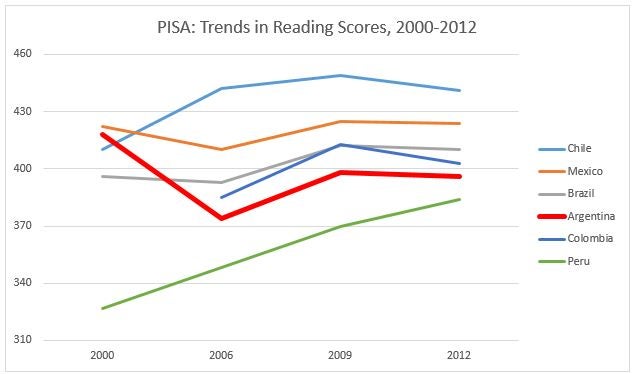

Among the best ways to become richer – as measured by GDP growth – is through increasing productivity which, in turn, requires a more educated workforce. Thanks to Eric Hanushek and Ludger Woessman, we now know that more education, as measured in years of schooling, is insufficient. It’s more learning that means more growth. To be precise, 100 points of PISA (an international assessment that measures 15-year-old students' reading, mathematics, and science literacy every three years) scores translates into 1.74 percent higher annual per capita GDP.

For Argentina, this is therefore a problem with long-term consequences for the poor. There has been virtually no improvement in learning since 2000, as measured by PISA scores. Yet, other Latin American countries including Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru have all seen gains, averaging more than 30 PISA points. Had Argentina kept pace with its neighbors on education, gaining even only 25 points, it could be seeing gains of 0.4 percent in GDP per capita over the long term. Considering the Argentina context, this translates into about $1,500 per person per year.

Why hasn’t Argentina’s education system been able to produce learning outcomes, like its neighbors? Let’s consider three possible culprits:

More inputs are needed. This could include more teachers, more money for infrastructure, ICT equipment, to name a few.

The system lacks efficiency. This refers to the country’s ability to take existing inputs (such as materials, personnel, or infrastructure) and transform them into learning. For example, this could include setting common learning goals for all actors in the system, having the necessary monitoring and evaluation system to track those goals and provide a clear diagnosis, and providing schools with technical assistance to transform the diagnosis into an action plan.

Exogenous factors over which education policymakers have no control. This includes crucial things such as previous learning outcomes, early childhood development, student motivation and expectations, among others.

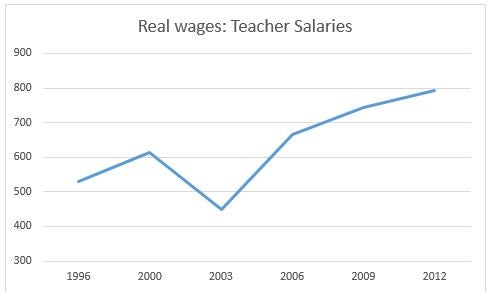

For starters, there is no shortage of financing. Thanks to Argentina’s education finance law of 2006 mandating a sector investment of six percent of GDP, and combined with high post-crisis economic growth, the country has mobilized massive amounts of resources to the sector in recent years. This resulted in a tripling of real resources between 2003 and 2013. This allowed for a sorely needed increase in real teacher salaries (of about 76 percent). But it also resulted in 20 percent more teachers, bringing the pupil-teacher ratio down to 11 (second lowest in the region after Cuba), a historic investment in school construction, and a massive investment in technology, laptops in particular.

As our recent paper notes, the lack of efficiency is driving trends in Argentina’s learning outcomes. Importantly, the student-teacher ratio variable has no correlation with improved learning, but the proportion of teachers with tertiary education does seem to matter – the quality of the teachers, not the quantity.

We then use the findings from the regression analysis to further decompose the learning effects, using microsimulations. That is, we create counterfactuals to respond to the question: “how would test scores in Argentina have evolved between 2000 and 2006 had the efficiency of the system been the only change observed during that period?

The simulation results show that the amount of inputs in the system hardly affected PISA scores. Rather, how efficiently those inputs were used in the production of learning is what drives learning trends. The decline in learning outcomes between 2000 and 2006 is largely explained by the drop in test scores of students in public schools, while much of the recovery between 2006 and 2012 is accounted for by improvements in socio-economic variables, such as the effects of wealth and mother’s education levels – variables over which the education system has no control.

This is the bottom line: Argentina’s StagLearning provides another example of the failure of input-based education financing policies.

Education inputs are still important in the learning process, but their impact is limited, and tends to diminish over time, if the system is unable to use them effectively. Instead, Argentine policymakers should focus on a robust student assessment system that brings learning into sharper focus, and helps teachers, schools, supervisors, and other actors to rally around the end goal of improving learning.

They should closely examine their monitoring and evaluation systems to make sure they provide schools with timely information. They can also consider school finance systems that reward performance. Finally, they should make sure their teachers have both a challenging and rewarding career path that offers them opportunities for advancement, supports them toward excellence, and recognizes them for their performance as the most valuable asset of the education system.

Rafael de Hoyos and Sara Troiano contributed to this blog.

Find out more about the World Bank Group’s work on education on Twitter and Flipboard.

Read about what World Bank education experts have to say about PISA.

Join the Conversation