In Haiti, about 90% of primary school-aged children are enrolled in school. While still falling short of universal enrollment, this is a big improvement over just two decades ago. But enrollment is just the first step in building human capital – many children will repeat a grade, and about half will drop out before completing primary school, leaving the school system without having mastered even basic language and math skills. Why does participation in school produce so little?

The Government of Haiti, supported by the Bank and the Strategic Impact Evaluation Fund, carried out classroom observations to help shed some light on this question. Using the Stallings classroom observation tool, observers sat in on classes in a random sample of 97 schools across Northern Haiti (one of the poorest parts of the country). The results of this work (available in full here in English and French) point to some surprising insights about what is going on inside Haiti’s classrooms:

- Teachers are present and teaching: Average time spent on instruction, at 76%, is 10-15 percentage points higher than in other LAC countries, as you can see in the figure below. This is consistent with results that show teacher absenteeism in this region of Haiti is lower than in other developing countries. Both the low rates of absenteeism and high rates of time on instruction are explained in part by the somewhat unique set of incentives Haitian teachers face -- over 80% of primary schools are non-public, where teachers are essentially at-will employees, and potentially have better accountability mechanisms. Even in public schools, where job security is higher, assurances of being paid are not, which may also motivate teachers to come to work in the hopes of eventually receiving payment.

- But their teaching methods are ineffective: Most instructional time is spent on lecturing or eliciting responses in unison from the class, and responses were often related to repetition and memorization. Teachers rarely acknowledged or corrected the many incorrect answers or lack of answers noted by observers. These methods have limited effectiveness in teaching children, especially young children, the foundational cognitive skills they need to succeed in school.

- Language is an issue as well as teaching methods: In Haiti, the mother tongue for most children is Haitian Kreyol, rather than French, and the Government’s official policy is to introduce reading and writing exclusively in Kreyol for the 1st grade. However, French was nearly three times more likely than Kreyol to be the subject matter of the 1st grade classes observed (34% versus 12%). This poses a problem for comprehension and learning, as both students and teachers appear to lack a mastery of French – only half of French reading or writing classes in the 4th-6th grades were observed being taught primarily in French.

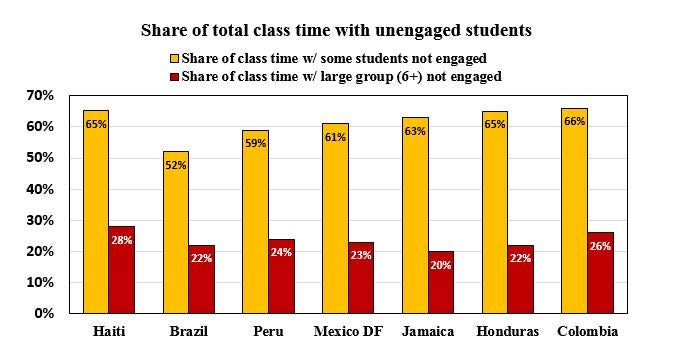

- Consequently, many students are unengaged and not getting much out of being in the classroom: Only about 35% of class time was spent on instruction with all students paying attention, lower than many LAC neighbors, as you can see below. The rest of the time, at least some students were playing, sleeping, or staring off into space. The study finds that classes with a higher share of time spent on instruction with all students engaged also have higher reading skills, suggesting that teachers who are able to engage their students do boost learning.

Beyond the many obstacles children and their families face in accessing school in the first place – costs (direct and opportunity) and other barriers (illness, natural disasters, lack of health and nutrition, etc.) – it is disheartening to learn that even when they surmount these and get to school, they are often not getting much out of it. These results make clear the importance of building teachers’ skills for effective teaching – in terms of pedagogical practices and content mastery (specifically language) – as a critical component of increasing educational achievement.

The Government, with the coordinated support of national and international partners, is in the process of developing a teacher training policy that could make a difference in learning outcomes if effectively designed. The ‘if’ is the critical part here – evidence from rigorous evaluations tends to show little impact of traditional teacher training programs, and the challenge is particularly large in Haiti where most teachers lack post-secondary degrees (and in many cases, secondary degrees). However, practical, specific, and sustained in-service training can substantially increase the effectiveness of teachers ( see an overview of the evidence here). By taking the lessons learned from these experiences and developing approaches that work for Haiti, getting teachers to teach more effectively will be a big step towards making school worthwhile for the children who put in the effort to be there.

Camille Simardone contributed to this post.

Follow the World Bank education team on Twitter and Flipboard.

Join the Conversation