Buy a leather case for your wife’s smartphone on Amazon, select shipping from China with an estimated delivery time of 4-6 weeks, and then be pleasantly surprised when it turns up on your Virginia doorstep in 11 days. The marvels of the modern age – of technology, globalization, and shrinking distances.

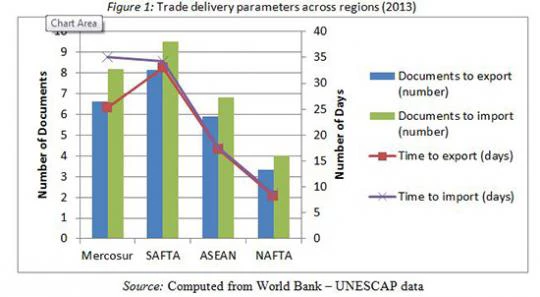

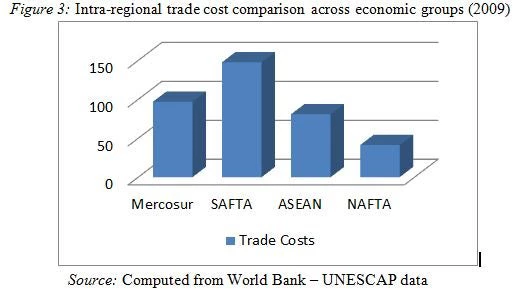

Where does South Asia stand on export delivery? Figure 1 illustrates that compared to other economic units around the globe, it is a lot more difficult to trade with(in) SAFTA (South Asia Free Trade Agreement). It also shows that bureaucratic hurdles and the time it takes to trade go hand-in-hand. While the region does relatively well on trade with Europe or East Asia, intra-South Asian trade has remained low and costly. It costs South Asian countries more to trade with their immediate neighbors, compared to their costs to trade with distant Brazil (see below)! In fact, it is cheaper for South Asian countries to export to anywhere else in the world than to export to each other (Figure 3). In other words, South Asia has converted its proximity into a handicap.

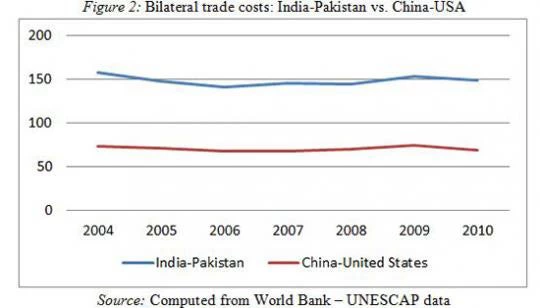

The two biggest economies in this region – neighbors India and Pakistan – exemplify the situation. Trade costs between these two neighbors are double the costs of trade between China and the US (Figure 2). Note that the distance between Beijing and Washington is 6,921 miles, while India and Pakistan share a 1,800 mile border. Only a handful of products (137) are allowed to be traded across the Wagah-Attari land border between the two Punjabs of Pakistan and India; the rest have to use the seaport of Karachi.

The level of trade costs and levels of intra-regional trade go hand-in-hand. Figure 3 shows that trade costs among SAFTA (South Asia Free Trade Agreement) members is highest when compared to other economic groups. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that intra-regional trade in South Asia is only 5% of its global trade, as compared to 30% for ASEAN.

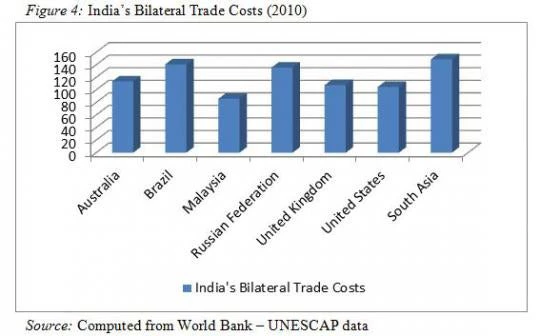

Figure 4 shows that India’s trade costs with neighboring South Asian countries are higher than those with countries in different regions - even those belonging to a different hemisphere.

Why is trade within South Asia so costly? There are many reasons, limited entry points being one, but let me discuss three other important ones. First, there is a widespread practice of transloading goods at the border, requiring them to be transferred from exporting country trucks into importing country trucks. The exceptions to this practice are limited.

Second, border clearances take time, arising from a lack of harmonization on standards and clearance protocols between border agencies.

Third, there are no transit agreements between the countries of South Asia, which would have allowed goods trucks to travel under bond across the region, unimpeded by restrictions or duty payments.

At one time, the Grand Trunk Road (the precursor to which was the ‘Sadak-e-Azam’, or the great path, allowed seamless movement of goods in South Asia, from Kabul in the West to Chittagong in the East. Today, while the various components of the road exist, the journey from Afghanistan to Bangladesh is very different. Both people and goods are better off using air/sea connections.

Addressing man-made obstacles to regional transit and trade facilitation is critical for South Asia, especially for its land-locked regions, including Afghanistan, Nepal, the North Eastern states of India and the North Western region of Pakistan. Reducing poverty in these regions will inevitably require better connectivity with sea and land routes. And we are talking about some large numbers here - Afghanistan and Assam each have about 10 million people living in poverty. Nepal has 6.7 million poor. Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, the isolated Northwest region of Pakistan, has about 7 million poor. (If we use the $1.25 poverty line instead of national poverty lines, the numbers will increase. For example, Assam’s poverty numbers go up to 12.6 million).

Fortunately, because current connectivity within the region is so far below potential, it is easy to see the upside. Plugging the connectivity gaps will help increase trade within the region, provide cheaper access to goods and services, create more jobs including along trading corridors, and ultimately help reduce poverty at a faster pace. This will help turn proximity from a barrier to the real advantage that it is meant to be.

Join the Conversation