For South Asia to achieve a sustained, long-term recovery, policy actions that promote resilience and boost productivity and innovation are a must. Photo: PradeepGaurs/Shutterstock.com

For South Asia to achieve a sustained, long-term recovery, policy actions that promote resilience and boost productivity and innovation are a must. Photo: PradeepGaurs/Shutterstock.com

Despite the ferocious resurgence of COVID-19 earlier this year, South Asia continues to recover, thanks to targeted lockdowns, accelerated vaccination rollout, and trade demand from outside the region. Industrial production and merchandise exports have reached or surpassed pre-pandemic levels, and the region is expected to grow by 7.1 percent in 2021 and 2022, per our latest South Asia Economic Focus, Shifting Gears: Digitization and Services-Led Development.

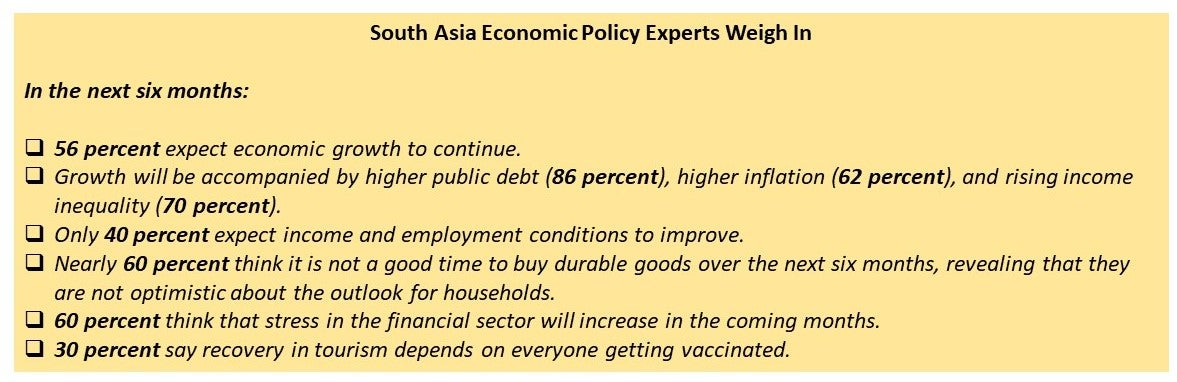

A network of more than 500 policy makers, academics, and macroeconomists across South Asia—part of the South Asia Economic Policy Network (SAEPN)—share this optimistic outlook for the region via our opinion survey:

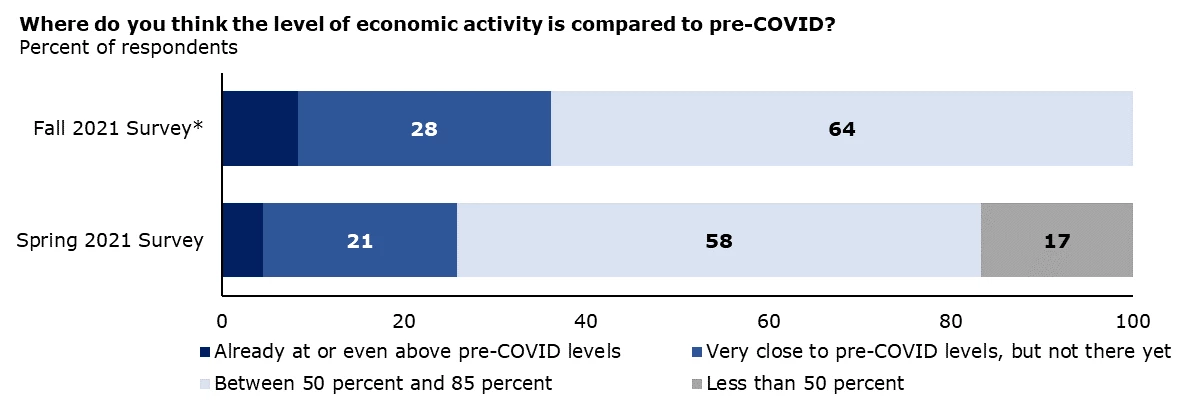

- Thirty-six percent believe that economic activity in the region is very close to or even above pre-COVID levels, compared to only 26 percent this past spring.

- Similarly, 52 percent now believe that tourism will return to pre-COVID levels this year or very soon, compared to 46 percent back in spring, showing an overall bullish outlook toward South Asia’s economic growth.

However, while South Asian economies have hit the road enthusiastically despite a global pandemic, this strong growth reflects a rebound from a very low base in 2020 and the average annual growth during 2020-23 is still three percentage points lower than it was in the four years preceding the pandemic.

What does this bode for South Asia’s economic recovery?

For one, South Asian countries will have to surmount weaknesses in their economies on the road ahead. As we argue in Shifting Gears, high public debt, elevated inflation, and rising inequality could all but constrict growth and development in South Asia.

Fiscal policies during the pandemic that focused on supporting relief efforts have increased public debt significantly in most South Asian countries, and the pandemic has highlighted the rising levels of public debt , as addressed in our recent report, Hidden Debt. Going forward, governments may not be able to spend either on further relief projects that support recovery or on public projects that promote growth and development.

Inflation has been elevated in many regional countries since the start of the pandemic, and in recent months, half of the South Asian countries have seen inflation rates higher than their historical averages. More importantly, due to rising global energy prices, the prices for food and fuel items have been rising even faster than general goods and services. This means, people will find it harder to afford basic items with rising prices.

While South Asian economies have hit the road enthusiastically despite a global pandemic, this strong growth reflects a rebound from a very low base in 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic has also created sharp rises in poverty worldwide, exacerbating inequalities and stifling efforts to reduce poverty. In South Asia, the pandemic is estimated to have led to 62-71 million new poor in 2020 and 48-59 million new poor in 2021 , defined as those who would either not have fallen into poverty or would have escaped poverty in the absence of the pandemic. Food insecurities have skyrocketed, with 46 percent of respondents from our regional surveys conducted between late 2020 and early 2021 reporting that their household would be unable to meet basic food needs beyond one month. In employment, 30-60 percent of workers who were ever economically active in 2020 lost earnings and wages. South Asia is home to more than 2.5 million refugees. Surveys of refugees in four South Asian countries conducted by the United Nations refugee agency (UNHCR) between late 2020 and early 2021 show that their basic needs are not covered : 33 percent of the respondents said they can meet only half their basic household needs and 8 percent stated they cannot meet basic needs at all.

As South Asia recovers from these tough circumstances, poverty and inequality will gradually return to pre-pandemic levels. But that process can take time, and poorer households will struggle to cope when relief programs stop, further exacerbating poverty and inequality.

South Asian countries should promote services-led development, given the unprecedented rise in digital technologies during the pandemic paired with the region’s competitive edge in services

Future COVID-19 waves and financial vulnerabilities

The risk of a new, more contagious or more deadly COVID-19 variant still haunts the region even as it emerges from the devastating waves of this past spring and summer. While South Asia has made tremendous progress with vaccinations—more than half of the region’s population has received at least one shot, compared to the world average of 48 percent —going forward, supply of vaccines remains the main bottleneck for the region.

Financial sector vulnerabilities existed in the region even before the pandemic. During the pandemic, low lending rates and loan forbearance programs have led to excessive borrowing, perpetuating ill health of the financial sector overall. As countries in the region end the forbearance programs and tighten monetary policy in the coming months, these underlying issues in the financial sector could manifest as further financial sector distress and damage the recovery.

Turning the tide

In the midst of these risks, how can recovery best happen? For South Asia to achieve a sustained, long-term recovery, policy actions that promote resilience and boost productivity and innovation are a must.

South Asia must build back better and Shifting Gears highlights two long-term growth strategies.

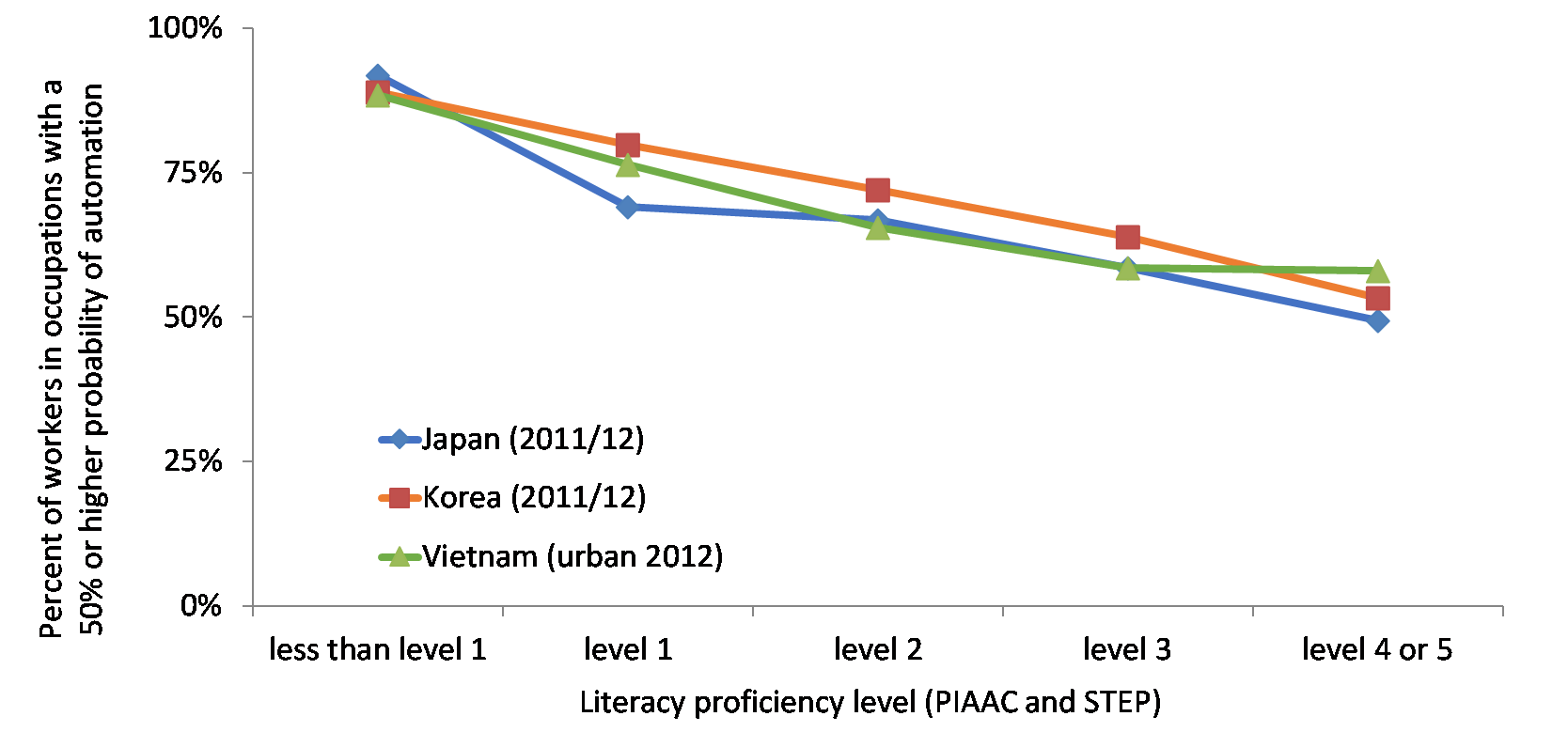

First, it is imperative that the region prepare for future shocks, including natural and manmade disasters by following a path of green, resilient, and inclusive development (GRID). Second, South Asian countries should promote services-led development, given the unprecedented rise in digital technologies during the pandemic paired with the region’s competitive edge in services. Digitization and services-led growth can create great opportunities for future jobs—we already see this approach empower women in India with the JEEViKA project and in Bangladesh with the HelloTask app. Experts agree that it behooves South Asia to shift gears from a traditional manufacturing-led growth model to capitalize on the potential of its services sector.

Overall, that’s how you can turn the tide in South Asia: Shift gears to promote long-term growth with the GRID approach and make services the driver of development. This might be the road less traveled, but it will enable long-term recovery across the region.

This blog is part of a series centered around the latest edition of our South Asia Economic Focus (SAEF)- Shifting Gears: Digitization and Services-Led Development.

Join the Conversation