How much social mobility is there in South Asia? The intuitive answer is: very little. South Asia is home to the biggest number of poor in the world and key development outcomes – from child mortality to malnutrition – suggest that poverty is entrenched. Absence of mobility is arguably what defines the caste system, in which occupations are essentially set for individuals at birth. Not surprisingly, the prospects for people from disadvantaged backgrounds to prosper are believed to be gloomier in this part of the world.

And yet, our analysis in Addressing Inequality in South Asia, reveals that economic and occupational mobility has become substantial in the region in recent decades. In fact, it could even be comparable to that of very dynamic societies such as the United States and Vietnam. The analysis also suggests that cities support greater mobility than rural areas, and that wage employment – both formal and informal – is one of its main drivers.

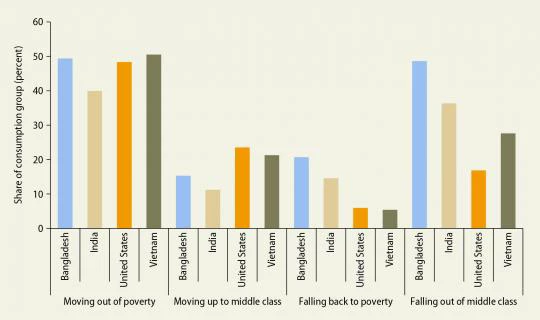

When splitting the population into three groups—poor, vulnerable, and middle class—upward mobility within the same generation was considerable for both the poor and the vulnerable. In both Bangladesh and India, a considerable fraction of households moved above the poverty line between 2005 and 2010. Meanwhile, a sizable proportion of the poor and the vulnerable moved into the middle class. In India, households from Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes – considered together – experienced upward mobility comparable to that of the rest of the population.

Source: Addressing Inequality in South Asia, World Bank 2014.

By these measures, upward mobility within a generation in Bangladesh and India was comparable to that of dynamic societies such as the United States and Vietnam. Per capita consumption is higher and poverty incidence is lower in the United States and Vietnam than in South Asian countries, but over a comparable period, the four countries saw similar fractions of the poor moving above the poverty line and a considerable fraction of the poor and vulnerable moving into the middle class. Downward mobility was much bigger in the two South Asian countries however, revealing the greater risks faced by the vulnerable and even the middle class.

Another finding of the report, somewhat less unexpected, is the contribution the rural-urban transformation is making to mobility in South Asia. At the village level, the occupational shift from farm to nonfarm employment has lifted many out of poverty. Migration, both internal and international, has also helped South Asians find better jobs and investment opportunities. But mobility is much greater in urban than in rural areas. Even urban households whose members are self-employed or who work as casual labor experience stronger upward mobility and smaller downward mobility than rural households.

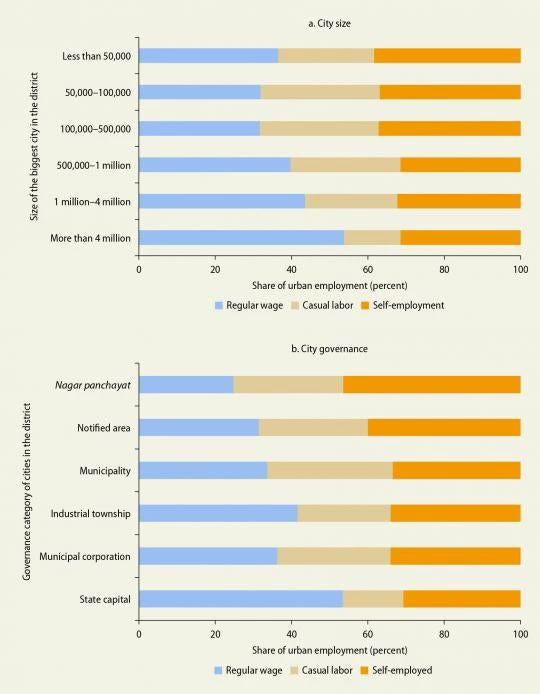

Cities are not all alike though. Urbanization is more organic in South Asia than it has been in East Asia. Whereas many South Asians migrate to cities, cities also “come” to them through the densification of population and the transformation of economic activity in rural areas.These diverse urbanization processes have led to a range of cities with different characteristics, not just in terms of their size but also in terms of their governance structure.

Source: Addressing Inequality in South Asia, World Bank 2014.

These differences in size and governance matter for mobility, because they shape the type of jobs available across different types of cities. In India, our analysis finds that districts with larger cities have a higher proportion of urban regular wageworkers than do districts with smaller cities. Between districts with cities of more than one million people and the other districts, the difference is large and significant. The share of regular wage jobs in urban employment broadly declines with the autonomy, capacity, and financial resources of city authorities. Districts with state capitals, municipal corporations, or industrial townships are associated with significantly greater shares of urban employment in regular wage jobs and in all wage jobs. The relationships hold even after taking into account the size category of the biggest city in the district. Better understanding and nurturing this dynamism should be the highest priority for those who care about addressing inequality.

Learn more:

Feature Story: Fundamental Reforms Needed to Effectively Tackle Inequality in South Asia

Press Release: Jobs and Migration Key to Addressing Inequality in South Asia

World Bank Live: Event Replay and Tweets from the Event

Interview with SAR Chief Economist Martin Rama

Launch Presentation (PDF)

Full Report: Addressing Inequality in South Asia

Join the Conversation