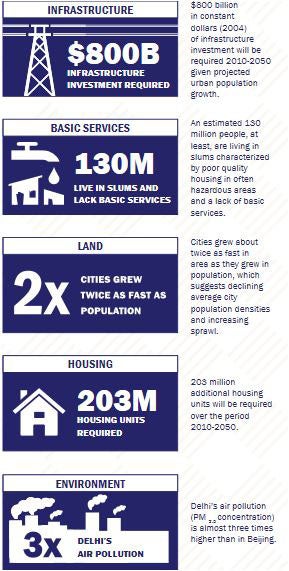

South Asia is not fully realizing the potential of its cities for prosperity and livability, and, according to a new report by The World Bank, a big reason is that its urbanization has been both messy and hidden. Messy and hidden urbanization is a symptom of the failure to adequately address congestion constraints that arise from the pressure that larger urban populations put on infrastructure, basic services, land, housing, and the environment.

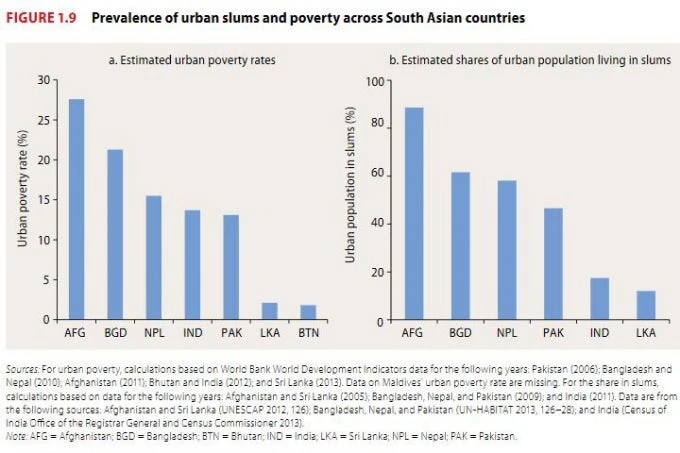

Messy urbanization is reflected in the region’s estimated 130 million people living in slums characterized by poor quality housing in often hazardous areas and a lack of access to basic services, according to the report: “Leveraging Urbanization in South Asia: Managing Spatial Transformation for Prosperity and Livability.”

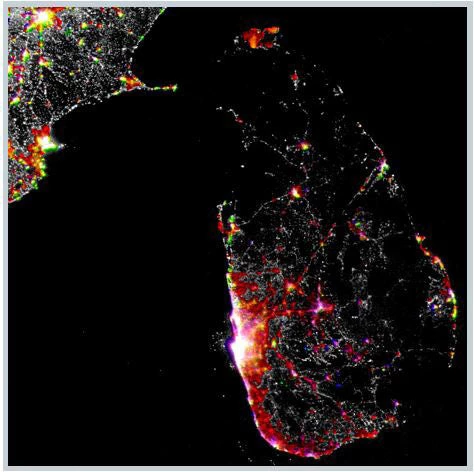

It also reflected in faster population growth on the peripheries of major cities in areas beyond municipal boundaries. Satellite imagery also shows that for many of the 12 largest Indian cities, the proportion of built-up area outside a city’s official boundaries exceeds that within its boundaries. For all 12 cities, the proportion of built-up area outside city boundaries exceeds the proportion of population. For Sri Lanka, messy urbanization also takes the form of ribbon development along major transport arteries. Night-lights data shows rapid growth between 2002 and 2012 (the red areas) on both the periphery of the Colombo metropolitan region and along major roads, such as that which connects Colombo with Kandy (Sri Lanka’s second most populous city).

The spillovers of cities across their boundaries create challenges for metropolitan coordination in the delivery of basic services and the provision of infrastructure. And the scale of the challenge has grown. That’s evident in the rapid spread of urban footprints. Analysis based on night-lights data shows that the region’s urban areas expanded at just over 5 percent a year between 1999 and 2010. But urban population growth for the region was a little less than 2.5 percent a year. So cities grew about twice as fast in area as they grew in population, which suggests declining average city population densities and increasing sprawl.

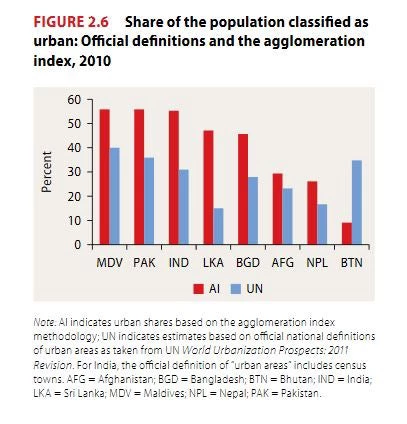

Sprawl, in turn, helps give rise to hidden urbanization, as towns and cities spill into administratively rural areas. Hidden urbanization stems from official national statistics that understate the share of South Asia’s population living in areas with urban characteristics. An alternative measure of urbanization, the agglomeration index – which, unlike official measures, is comparable across countries and regions – shows that official statistics may substantially understate the number of South Asians living in areas that look and feel urban, even if they are not counted as such in national population and housing censuses.

This undercounting is in addition to the population in India’s census towns, which are towns that the country’s census classifies as urban even though they continue to be governed as rural entities. The reclassification of rural settlements into census towns was responsible for 30 percent of India’s urban population growth between 2001 and 2011, reflecting a more general process of in situ urbanization across much of the region.

To read the full report, go to: www.worldbank.org/southasiacities

Join the Conversation