Last week, a tanker truck, one of many roaming the streets of Kabul, navigated through bumper-to-bumper traffic, going past government buildings and embassies, to Zanbaq Square. When stopped at a checkpoint, more than 1,500 kg of explosives that had been hidden in the tank were detonated. It was 8:22 am and many Afghans were on their way to work and children were going to school. The explosion killed 150 commuters and bystanders, and injured hundreds more. This is just one of many incidents that affects Afghans’ lives and livelihoods.

Conflict has constantly increased over the past years, spreading to most of Afghanistan, with the number of security incidents and civilian casualties breaking records in 2016. According to the Global Peace Index, Afghanistan was the fourth least peaceful country on earth in 2016, after Syria, South Sudan, and Iraq. The intensification and the geographical reach of conflict has increased the number of people internally displaced. According to the latest United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) data, over 670,000 people were internally displaced in 2016 alone.

Against this backdrop, our recent World Bank report, the “Afghanistan Poverty Status Update: Progress at Risk”, shows that not surprisingly violence and insecurity pose increasing risks to the welfare of Afghan households. Approximately 17 percent of households reported exposure to security-related shocks in 2013–14, up from 15 percent in 2011–12 according to data from the Afghanistan Living Conditions Survey (ALCS)[1]. This is largely in line with the actual incidence of conflict incidents as reported by the United Nations Department of Safety and Security (UNDSS).

Conflict exacerbates vulnerability and worse still, households living in high-conflict districts are exposed to more non-security related shocks. For instance, households in high-conflict areas are more likely to report agricultural, natural hazards, and epidemic shocks in addition to security-related ones. Approximately 53 percent of households in high-conflict districts reported three or more non-security-related shocks compared to 43 percent in low-conflict districts in 2013–14. In addition, exposure to higher conflict is associated with greater reliance on harmful coping strategies and lower human capital investments – providing adequate nutrition and education for children - particularly for the poor.

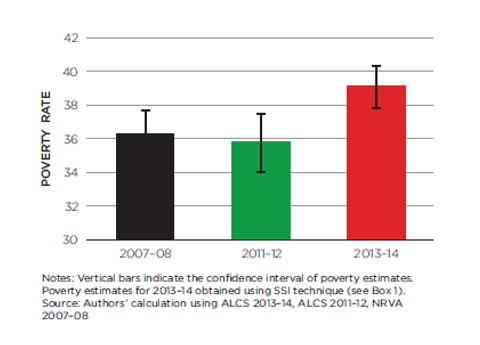

While increasing conflict has made Afghans more vulnerable to shocks - the period between 2012 and 2014—the so called “transition period” leading to the 2014 election and handover of security responsibility to Afghan forces— was characterized by a severe slow-down in economic growth caused by reduction of aid, drawdown of international military forces, and political  instability. The report shows that this led to troublesome socio-economic dynamics, magnifying the many inequalities—between rich and poor, cities and rural areas, men and women, and girls and boys—that fracture Afghan society. The poorest and most vulnerable segments of the population suffered the most, with sluggish growth and increasing conflict pushing 1.3 million more Afghans into poverty since 2011-12, increasing the poverty rate from 35.8 percent in 2011–12 to 39.1 percent in 2013–14. This trend confirms once again the extreme vulnerability of Afghan households to the risk of falling into poverty when hit by a negative shock. Between 2011–12 and 2013–14, average per capita consumption declined at an annual rate of 1.7 percent, but the decline was particularly severe at the bottom of the distribution. While the poorest 20 percent of the population saw a 4.2 percent decline in real per capita expenditure over the period, the decline for the richest 20 percent was only 2.8 percent.

instability. The report shows that this led to troublesome socio-economic dynamics, magnifying the many inequalities—between rich and poor, cities and rural areas, men and women, and girls and boys—that fracture Afghan society. The poorest and most vulnerable segments of the population suffered the most, with sluggish growth and increasing conflict pushing 1.3 million more Afghans into poverty since 2011-12, increasing the poverty rate from 35.8 percent in 2011–12 to 39.1 percent in 2013–14. This trend confirms once again the extreme vulnerability of Afghan households to the risk of falling into poverty when hit by a negative shock. Between 2011–12 and 2013–14, average per capita consumption declined at an annual rate of 1.7 percent, but the decline was particularly severe at the bottom of the distribution. While the poorest 20 percent of the population saw a 4.2 percent decline in real per capita expenditure over the period, the decline for the richest 20 percent was only 2.8 percent.

Poorest Afghans were the least able to navigate the crisis, both because they lacked the means to cope with shocks and because the crisis was particularly severe in rural areas where the large majority of poor people live. Poverty in rural areas increased by 14 percent between 2011–12 and 2013–14, going from 38.3 percent to 43.6 percent. On the other hand, poverty in urban areas did not change over time despite substantial migration flows from rural to urban areas.

Our report shows that Afghan households have been negatively affected by the crisis induced by the security and political transition. With growth unlikely to reach pre-transition levels and a probable continuation of conflict and fragility, Afghanistan’s development and poverty reduction will likely be constrained moving forward. Such poverty and inequality trends, if left unattended, could further undermine social cohesion and jeopardize progress. To address poverty and inequality, it is important to achieve improvements in security and in overall economic performance, which are difficult under current conditions. Nevertheless, as discussed at the latest donor conference in Brussels on Afghanistan in 2016, where donors pledged over $15 billion over the next 4 years, poverty reduction in Afghanistan will require growth to be much more inclusive and broad-based than in the past.

2013–14”, Central Statistics Organization of Afghanistan.

Join the Conversation