The world economy today presents itself as a diverse canvas full of challenges and opportunities. Advanced economies continue to struggle towards recovery, with the US on its way to tighten monetary policy as the economy picks up while a still weak Eurozone awaits quantitative easing to kick in. At the same time, plunging oil prices have set in motion significant real income shifts from exporters to importers of oil. Astonishingly, amidst all this turmoil, South Asia has emerged as the fastest growing region in the world over the second half of 2014. Led by a strong India, South Asia is set to further accelerate from 7 percent real growth in 2015 to 7.6 percent by 2017, leaving behind a slowing East Asia gradually landed in second spot by China.

While bolstered by record low inflation and strong external positions across the region, the biggest question yet to be addressed by policy makers in South Asia will be how to make the most of cheap oil.

All countries are net oil importers as well as large providers of fuel and related food subsidies, therefore bound to benefit from low oil prices. However, the biggest oil price dividend to be cashed in by South Asia is one yet to be earned, and not one that will automatically transit through government or consumer accounts. The current constellation of macroeconomic tailwinds provides a unique opportunity for policy makers to rationalize energy prices and to improve fiscal policy. Decoupling external oil prices from fiscal deficits may decrease vulnerability to future oil price hikes – something that may very well happen in the medium term. Furthermore, cheap oil offers a great opportunity to introduce carbon taxation and address the negative externalities from the use of fossil fuels.

The World Bank’s latest South Asia Economic Focus (April 2015) titled “Making the most of cheap oil” provides deeper insights regarding South Asia’s diverse policy challenges and opportunities stemming from cheap oil.

A first major realization is that the pass through from oil prices to domestic South Asian economies is as diverse as the countries themselves, thanks to a variety of different policy environments across countries and oil products. This is also reflected in recent dynamics, seeing India taking determined action towards rationalizing fuel and energy prices, even introducing a de facto carbon tax and beginning to reap fiscal and environmental benefits. Other countries have so far shown less or no enthusiasm towards reform, in spite of significant and/or increasing oil dependency (particularly in electricity generation, one of the region’s weak spots).

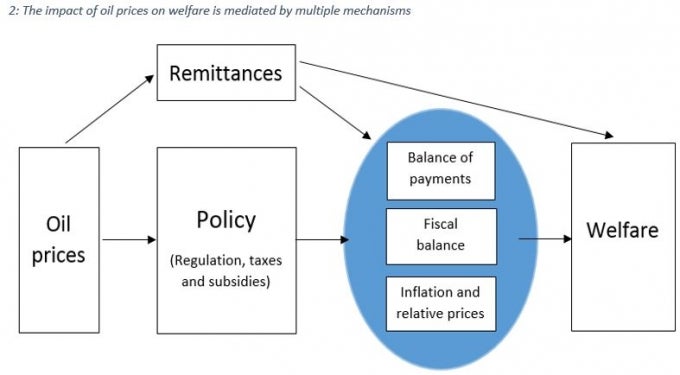

Second, our macroeconomic analysis reveals interesting insights regarding how oil price declines may be absorbed in South Asia’s largest economy, India. Overall, oil price shocks will affect the economy mainly through current account balances and fiscal accounts. In the middle term, trade balances will also improve on the back of cheaper oil imports, however, given oil exports are sizable and more elastic, short run trade deficits may slightly increase. Remittances may very well take a hit eventually, however, current responses are modest and any potential reaction will to a large extent depend on the policy response of Gulf countries. Fiscal deficits are to decline following lower subsidy bills. Based on India’s experience during 1995-2014, a 20 percent decline in international oil prices should lead to a 10-to-15 percent decline in the budget deficit. This is mainly the result of lower spending on energy subsidies. But the policy cushioning of the impact also results in more modest impacts on inflation and on economic activity. Overall, the same 20 percent decline in oil prices leads to an increase in India’s GDP by roughly 0.5 percentage points over four quarters.

Third, households will unambiguously gain, but richer households will gain more. The decline in oil price affects household welfare directly through the resulting change in the domestic price of oil products, and indirectly through its overall impact on economic activity. Both direct and indirect welfare effects in Bangladesh, India and Pakistan are positive and not negligible, but they are skewed towards richer households. The regressive nature stems from relatively lower shares of oil products in total consumption expenditure for poorer households. Overall effects in terms of predicted change in consumption expenditure power range from a gain of 2 percent for households in the poorest decile to a gain of 4 to 5 percent for those in the richest decile.

Future development in oil prices is surrounded by great uncertainty, therefore governments and firms alike may want to explore available hedging options. However, a more workable option to reduce fiscal vulnerability in face of large international commodity price swings is to take advantage of cheap oil to cut energy subsidies. Furthermore, current tailwinds for fiscal balances may send the wrong signal to fiscal policy makers and take off pressure from addressing on of South Asia’s key domestic challenges, structural weaknesses in revenue generation. Altogether, these arguments constitute a solid case for taking the opportunity to replace risky subsidies with other support measures and transfer schemes able to better target those in as well as to reform poor performing electric utilities and state owned refineries that are often highly subsidized.

In conclusion, now is the time to seize the opportunity to rationalize energy prices and permanently insulate fiscal balances from oil price swings, thereby making the most of cheap oil in South Asia.

Join the Conversation