Photo by: Shahadat Rahman Shemul

Watching export growth across South Asia surge in the recent past leads one to ask the obvious but crucial question: Will this trend continue in the longer term and is South Asia on its way to become an export powerhouse, or has it just been a short term, one-off spurt provoked by external forces?

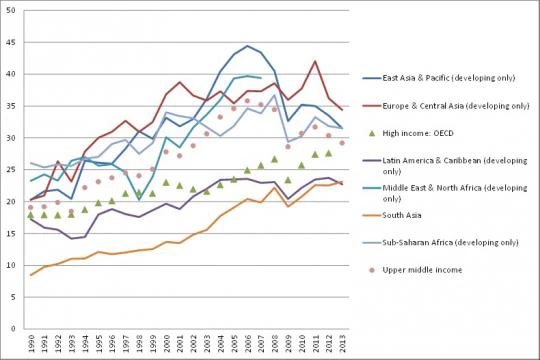

Clearly, the rupee depreciation following tapering talk in May 2013 and the recovery in the US constituted favorable tailwinds; however, our analysis in the fall 2014 edition of the South Asia Economic Focus finds that there are more permanent factors at play as well. South Asia is no exception to the trend across developing countries of increasing importance of exports for economic growth. While starting from a low base, the region saw one of the starkest increases in exports to GDP, pushing from 8.5 percent in 1990 to 23 percent in 2013.

Across many South Asian countries, exports are not only growing faster than GDP, and growing in volumes rather than just in prices: they are also becoming more diversified in terms of traded products and trading partners. So why is this important? In a nutshell, diversification has two crucial potential benefits: First, diversification across export lines bears greater potential to climb up the quality and value added ladders, thereby enabling higher margins. This may ultimately contribute to the observed positive correlation between diversification and GDP growth. Second, greater diversification by traded products and trading partners helps exporters to be more resilient against international shocks and to strategically rebalance their portfolio, as has been the case for South Asia shifting exports towards emerging markets (e.g. China). Reduced export and output volatility, on the other hand, greatly contributes to overall macroeconomic stability, a necessary condition for GDP growth.

Another important determinant of exports is the exchange rate. In fact, real (effective) exchange rates (REERs) can “make or break” export performance. While improving terms of trade lead to inflows of foreign exchange and an appreciating real exchange rate, i.e. exports become relatively more expensive in the importing country, there may be other sources of substantial capital inflows that can significantly appreciate the exchange rate and give rise to a phenomenon called Dutch Disease (coined after the consequences of oil revenue from the North Sea on the Dutch economy in the 1960s).

Dutch Disease implies the reallocation of resources such as labor to the sector associated with the foreign currency bonanza. This in turn makes potentially competitive exports in other sectors more expensive. Also, the foreign money coming into the country boosts domestic demand more generally, increasing both the imports of tradable goods – in particular manufactured goods – and the domestic prices of non-tradable goods. Ultimately these resource allocation and spending effects may combine into a decline in manufacturing growth vis-à-vis services growth and yield lower long term GDP growth.

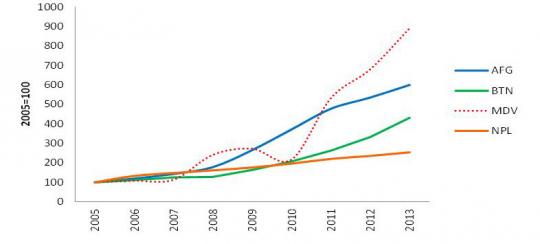

The South Asian countries potentially suffering from Dutch Disease are Afghanistan, Bhutan, Maldives and Nepal. Though their sources of FX inflows vary greatly – from foreign aid in Afghanistan, hydro export receipts in Bhutan, to tourism receipts in Maldives and remittances in Nepal – they all show classical symptoms: appreciation of REERs, dramatic growth in real wages and relatively subdued manufacturing growth.

2, Exchange rate appreciation translates into fast growth of real wages

In sum, South Asia’s strong export performance does not seem to be a one-off effect. It rather signals the great export opportunity the region faces today. The local variant of Dutch Disease may hold back export performance particularly in Afghanistan and Nepal. But except in these cases, the prospects for continued growth are encouraging. Exports become ever more diversified, setting the stage for further quality upgrading and hedging against external shocks. And there is little risk that they will be damaged by further monetary tightening in the US, as the impact of tapering has been fully internalized by markets already.

Then, with East Asian labor costs increasing and overall growth slowing down, South Asia has a unique opportunity to become an export powerhouse, especially in light manufacturing sectors. And the region may be well placed to seize this opportunity. But the chances of success will depend on policy makers’ attention to more efficient regulation, improved infrastructure as well as maintaining a conducive macroeconomic policy environment.

Learn More:

Press Release: Led by India, South Asia Economic Growth to Accelerate, World Bank

Factsheet: South Asian Countries Show Potential for Accelerated Growth

Full Report: South Asia Economic Focus: The Export Opportunity

Video Interview: Chief Economist Martin Rama

Join the Conversation