Banking transaction, Tajikistan

Banking transaction, Tajikistan

Under economic stress, people often resort to desperate financial choices to sustain their income and provide for their families. This includes speculating with complex financial derivatives or engaging in pyramid schemes, as many did during the pandemic. Since January 2021, over 31,000 people in Kazakhstan fell prey to financial pyramid schemes, losing a total of 54 billion KZT ($121 million), while in the Kyrgyz Republic, monetary damages from pyramid schemes amounted to over 311 million soms ($3.8 million) in the first year of the pandemic.

The war in Ukraine, sanctions, and disruptions to corresponding banking and formal remittance channels will bring more economic stresses to the region, leading some to take desperate financial actions to sustain their incomes and lifestyles.

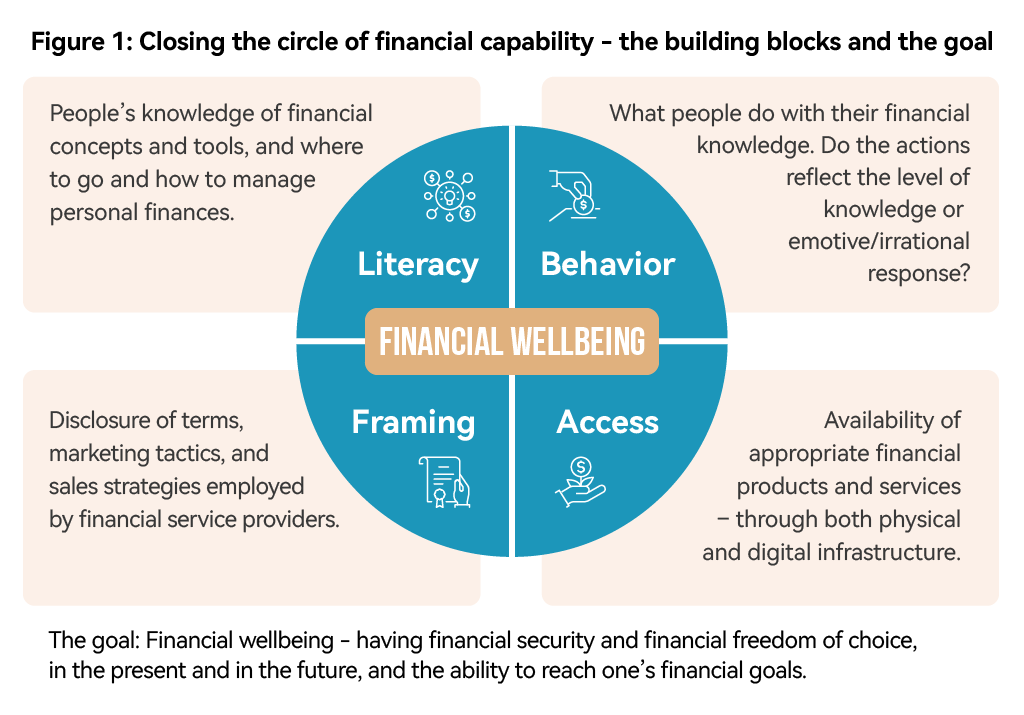

Thankfully, financial literacy has been gaining more attention in Central Asia, with banks organizing roundtable discussions and learning courses, extracurriculars offering financial literacy classes to children, and policymakers delivering educational resources and programs. But literacy is just one piece of the financial capability puzzle that, when assembled, fosters the journey toward financial wellbeing—financial security, financial freedom of choice, and an ability to achieve one’s financial goals.

What needs to be done then to promote financial wellbeing for more people in Central Asia?

To start, we need to redefine the conversation by focusing on the holistic concept of financial capability that can help people achieve the goal of financial wellbeing and discuss its four building blocks.

The four building blocks of financial capability

In addition to financial knowledge, financial behavior, access, and framing shape a person’s financial capabilities.

1. Central Asia is marked by disparities in financial knowledge. For example, people across the region are most challenged by the concept of “compounding,” key to understanding how savings can grow over time but also how debts can dangerously deepen. Although data suggests that people in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan may understand “compounding” better within the region, retail loans in Kazakhstan still grew much more than household income for several years and despite the high interest rate of about 19 percent on average. In addition, the pandemic left many people jobless, and they rely on loans to pay other debts.

2. Financial behavior of people in Central Asia reveals impatience with finances, often focusing on immediate consumption. And when impatient behavior meets lower financial knowledge, people are more prone to bad financial choices. Such attitudes stand out in Kazakhstan and Tajikistan, where people often manage their finances to achieve immediate goals typically related to consumption as opposed to maintaining family emergency funds, savings for children’s education, or retirement plans. In the two countries, a larger share of people “completely agree” with statements such as “I find it more satisfying to spend money than to save it for the long term” or “Money is here to spend.” Moreover, financial behaviors are shaped by social norms and expectations, and people in Central Asia often take their decisions under such pressures.

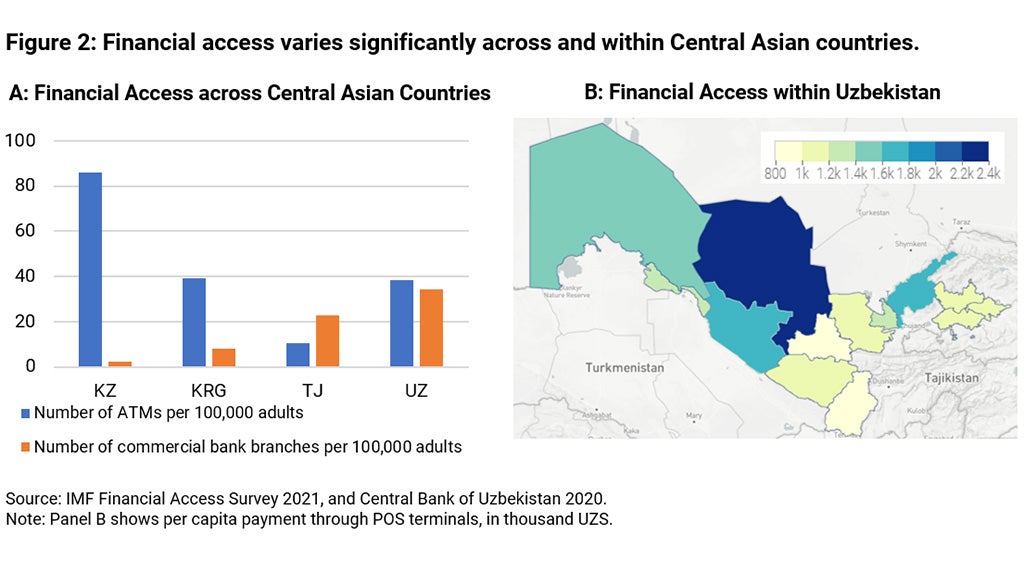

3. While financial access varies significantly across the region, it varies even more within countries. Banks and other financiers must provide consumers with access to suitable financial tools that genuinely help people manage the risks they face and seize development opportunities—tailoring their products to local needs. In Central Asia, impaired access to some basic financial services can narrow financial choices for some and leave those in rural areas at a disadvantage (Figure 2, panel A). And as Figure 2, panel B shows, regional variations in financial access within countries are often more pronounced than the cross-country differences. In Uzbekistan, for example, Tashkent contains 25 percent of all bank branches despite having only 8 percent of the country’s adult population. Across Uzbekistan, only 13 percent of administrative units have at least one financial access point, such as a bank branch, Infokiosk, or ATM.

4. Banks and financiers in Central Asia need to better frame and communicate about access to financial services. Financial service providers can exploit their market power, the lack of financial knowledge, and behavioral failures of people in Central Asia to pass on risks and costs to financial consumers that may harm their financial wellbeing—as happened in Kazakhstan before 2019, when banks applied hidden and illegal fees. The COVID crisis also led many people in the region to find new sources of income, often turning to high-risk investments in Forex markets, leading to cases of internet frauds offering pseudo-access to trades in FX and other financial instruments. In fact, major Tajik banks had often been extending foreign currency denominated lending to unhedged borrowers without helping them understand the foreign exchange risk they assume. This practice was later banned by the National Bank of Tajikistan.

The bottom line is that people in Central Asia need well-rounded financial policies that go beyond financial access and education. For example, the region needs financial consumer protection that ensures a fair framing of financial access that levels information asymmetry and power between suppliers and consumers—and does so in a way that does not stifle financial innovation.

To design better policies and improve Central Asians’ financial wellbeing, more robust diagnostics are required, involving contextualized impact evaluations, focus group interviews and surveys. Well-designed policies must also be properly coordinated in implementation across all stakeholders, periodically evaluated, and adjusted for maximum impact. That is where the World Bank Group is stepping in, assisting governments—most recently in the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan—to develop well-informed and comprehensive national financial inclusion strategies and policy action plans for their implementation.

Together, we can help more people in Central Asia reach a state of financial wellbeing: help them better plan and achieve their financial goals and be better able to absorb shocks and cope with crises—thus fostering a more resilient and inclusive progress in Central Asia.

Join the Conversation