A trained medical staff listens to the hearbeat of an infant at 16 Makara hopsital in Preah Vihear, Cambodia. The hopsital is able to attract high quality medical staff because they are offered incentives through the Health Service Delivery Grant. Preah Vihear province, Cambodia. Photo: Chhor Sokunthea / World Bank

A trained medical staff listens to the hearbeat of an infant at 16 Makara hopsital in Preah Vihear, Cambodia. The hopsital is able to attract high quality medical staff because they are offered incentives through the Health Service Delivery Grant. Preah Vihear province, Cambodia. Photo: Chhor Sokunthea / World Bank

Frontline healthcare workers have been essential in the ongoing public health crisis, and their importance and contribution cannot be overstated. However, governments, especially in low-and middle income countries, are confronting rising levels of public debt and the need to cut public expenditures to ensure macroeconomic stability. Balancing these policy objectives requires sound data and evidence, given the labor-intensive nature of health service delivery.

Drawing on the Worldwide Bureaucracy Indicators (WWBI) dataset we highlight in this blog the size of the public sector healthcare workforce, whether it is an equitable and representative employer, and we explore whether public sector wages are competitive enough to attract qualified candidates and keep them motivated.

The healthcare workforce provides critical services, and much of this provision takes place in the public sector.

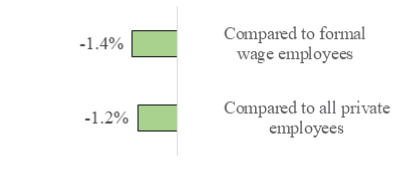

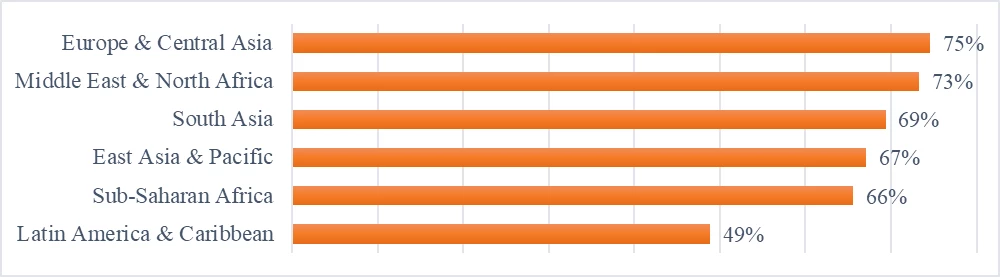

Globally, on average, 64 percent of all salaried healthcare workers are in the public sector, 75 percent in Europe and Central Asia, and 49 percent in Latin American and the Caribbean (Figure 1). This is due in large part to historical factors, limited state ability or demand for private healthcare services, especially in developing countries.

Figure 1: Public sector employment, as a share of paid employment, healthcare industry

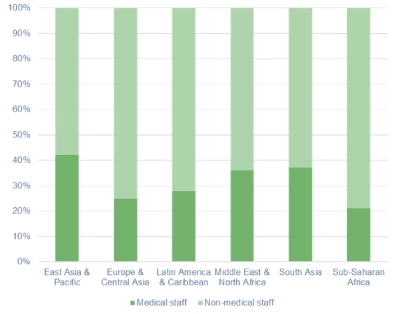

Global public sector healthcare systems show disproportionate employment in administrative roles over direct patient care, with significant regional variation.

Most personnel do administrative functions rather than direct patient care, with significant variance among regions (Figure 2), amounting to more than 75 percent in Europe and Central Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. This could create imbalances in the allocation of resources. To address this, it may be necessary to restructure administrative functions and decrease expenses, in order to allocate resources to caring for patients.

Figure 2: Public sector healthcare workforce by function

Public healthcare employees in most nations receive a wage premium compared to similar workers in the private sector, reaching, on average, 22 percent higher basic wages.

Compared to their private sector counterparts, the magnitude of the premium depends on job composition and characteristics of public sector health workers who have a sizeable wage premium at 22 percent. However, restricting the analysis to frontline personnel alone, the premium becomes a wage penalty. This could be due to salary caps and other limitations on earning potential, while the private sector may have the flexibility to offer higher salaries and bonuses to attract and retain highly skilled workers.

To illustrate this further, if a large part of the wage bill spending is driven by administrative workers, there may be less funding available to attract and retain critical medical professional to care for patients. More research is needed to establish whether higher wages will incentivize better services.

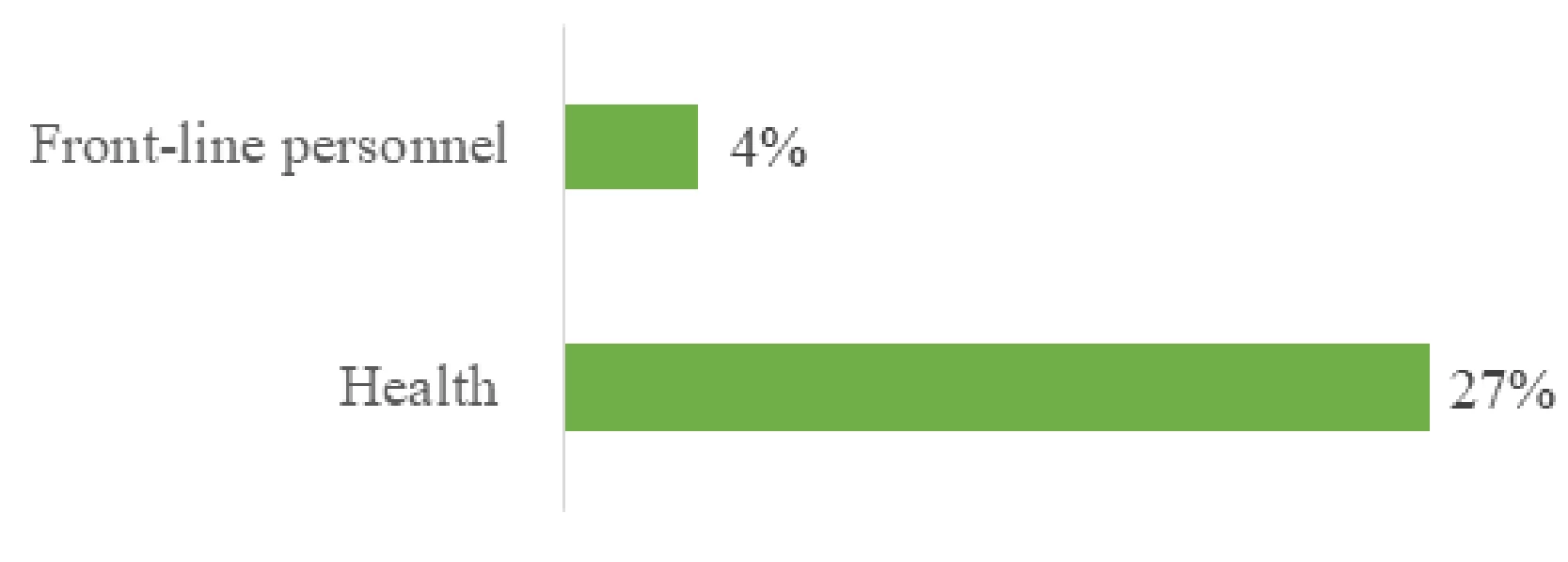

Figure 3: Public sector wage premiums for healthcare workforce

A) Public sector wage premium, by industry: Health

B) Public sector wage premium, front-line personnel

The healthcare sector has a long history of being one of the few options for female employment in many developing countries, yet still has gender gaps in compensation.

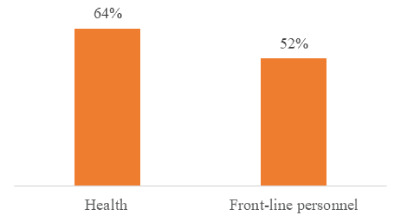

Women occupy a significant majority of the administrative and medical staff positions in the public sector, at 64 and 52 percent respectively (Figure 4A). Yet, a recent report finds that they are highly concentrated in low-level positions. While nearly 84 percent of 28.5 million nurses and midwives around the world are women, they are still outnumbered by male physicians. This gender imbalance in healthcare is a global phenomenon which is related to the persistent gender stereotypes that influence hiring practices in healthcare.

Looking at wage differentials, globally, women in the public sector enjoy almost a 30 percent wage premium. Yet it is much smaller – 27 percent – in the health sector when compared to all-paid wage employees. The public sector earning premium gets much smaller when we explore the wages of frontline women personnel (Figure 4B). Women in the public sector enjoying a wage premium compared to their private sector counterparts could reflect a commitment to providing fair wages and benefits for women. However, the smaller premium for female healthcare staff compared to all-paid wage employees may suggest that there is still room for improvement in the compensation policies.

Figure 4: Gender equity in the public sector healthcare

A) Females, as a share of public paid employees

B) Public sector wage premium for females (compared to paid wage employees)

Better data on staffing levels could lead to better distribution of healthcare workers to areas of greatest need, reduced workload and burnout among staff, and improved patient outcomes. Overall, evidence-based approaches to manage health personnel could result in a more effective and sustainable healthcare system.

Editor’s note: This blog post is part of a series for the 'Bureaucracy Lab', a World Bank initiative to better understand the world's public officials.

Join the Conversation