Relationships with affected communities can make or break mining activities. From a business perspective, local disputes can lead to more than US$20 million per week in losses for large-scale mines. To say nothing of the broader costs – in terms of lives lost and development stymied – when local discontent develops into violent conflict.

In response, a growing number of mining companies and governments have rolled out “Community Development Agreements” (CDAs), an umbrella term covering formal arrangements for local development between a company and designated communities. CDAs can run the gamut of the community-company relationship, including among other areas, socio-environmental impacts, benefit sharing, employment, monitoring and grievance redress.

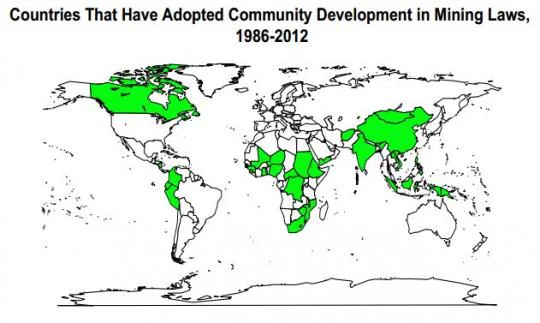

CDAs have spread quickly in national law and policy. Since the mid-1980s thirty two countries have adopted community development provisions in mining codes, with nine countries currently in the process. The CDA model, it seems, is an emergent “best practice” and initiatives ranging from the Ruggie Principles to the International Council on Mining and Metals have reiterated their value.

Policy makers and practitioners often argue CDAs are beneficial because communities have a greater say in their own governance, they reduce conflict by establishing grievance management systems, and communities arguably achieve better development outcomes as resources are channeled directly to their stated needs.

Do these claims stand up? Despite some inklings of “substantial implementation failure in relation to [such] agreements,” empirical work and policy dialogue are in short supply. What exists focuses on the terms of the agreement, rather than its participatory processes and implementation mechanisms, which are just as, if not more, important.

There is marked variation globally in investment in such processes and resultant outcomes. The much-lauded Newmont Ahafo Gold Project CDA followed a three-year capacity-building and negotiation process. By contrast, in the Liberian forestry sector, a template CDA has typically been presented to rural communities for signature without consultation or explanation and has done little to assuage community grievances.

The World Bank is partnering with clients such as Sierra Leone to address these learning and implementation deficits. Prior to the Ebola outbreak, Sierra Leone was one of several countries systematically putting CDAs into practice. Its 2009 Mining Act and regulations contained CDA provisions which established elements including revenue sharing, transparent communal governance, and gender strategies. Implementation, though, lagged. To date no CDAs satisfying the Act’s requirements have been signed.

A promising start was derailed in 2014, when the Ebola outbreak halted early-stage roll-out processes and operational suspension at the country’s two largest iron ore mines dealt a severe economic blow. But these challenges, and in particular the Ebola outbreak, also laid bare two key principles.

First, Sierra Leone’s economic recovery depends on extractives revenues. And second, fragility and conflict stresses need to be addressed strategically, as they are likely to challenge recovery efforts in the same way that they hindered the initial outbreak response. Recognizing these realities, the National Minerals Agency is taking immediate steps to resume the roll-out of CDAs as part of a fragility-sensitive strategy to build citizen-state-investor partnerships and harness investments’ development dividends.

So far, a small multistakeholder group led by the National Minerals Agency, and including the World Bank, has developed a model agreement which will serve as a stepping-off point for mine-site-specific negotiation and implementation. Even at this early stage, before community engagement has begun in earnest, there are a number of key challenges.

In one community, a Paramount Chief makes clear that she will vehemently oppose any calls for increased transparency as an infringement on her gate-keeping role. In another, there is a question of whether engaged CSOs have the financial literacy, let alone fuel stipend, to effectively monitor compliance. Elsewhere, decision-makers grapple with criteria for discerning an eligible “primary host community” (should it be based on proximity, impact or ability to cause trouble?).

Indeed, though CDAs have great potential to contribute to shared prosperity and real local partnerships, this potential is not self-fulfilling. The hazards include not just a missed opportunity for positive development outcomes, but a disruption of existing informal agreements which risks new waves of conflict. This makes it all the more critical for stakeholders to generate and share knowledge on how to wield these potentially transformative tools effectively.

Whether and how CDAs should be implemented should not rest on some notion of formal appeal, but rather understanding the determinants of success and failure in enhancing local development, governance and conflict outcomes.

Join the Conversation