Editor's note: This blog post is part of a series for the 'Bureaucracy Lab', a World Bank initiative to better understand the world's public officials. In December, the Bureaucracy Lab asked for PhD students to send us their proposals for blogs that summarize their bureaucracy-related job market papers/research. Thank you to all the entrants. Shan Aman-Rana, of the London School of Economics, is the worthy winner, and her blog post is below.

Today, decision-making in most bureaucracies is based on rules. Why is that? Starting from Northcote, Trevelyan & Jowett, B. (1854) and Weber (1922), it has been argued that if bureaucracies rely on discretion, it will result in favouritism and collusion with substantial welfare and organizational costs.

This argument has dominated the intellectual debate for so long that it is almost taken for granted that bureaucracies will always have rule-based decision-making. However, allowing discretion in organizations has its advantages. Consider the case of promotions. In most organizations there is a lot of decentralized information that is relevant for personnel management decisions.

For example, senior colleagues potentially know more about the ability and effort of juniors than any centralized human resource department. If organizations gave discretion to senior colleagues to promote junior workers, then there is a chance that the organization could make better use of seniors’ information on junior workers.

Three key questions

My job market paper takes these ideas to the data and aims to answer three questions:

- Whether with increase in promotion-power of senior colleagues, are high-merit juniors more likely to be promoted than the low-merit juniors?

- If yes, then what can be potential mechanisms behind meritocracy of discretionary promotions?

- Do seniors use not just public but private information on juniors meritocratically?

Context and data

The bureaucracy I study is the Pakistan Administrative Services (PAS) civil services in Punjab. PAS is an elite cadre of civil servants responsible for running all key government departments and implementing UN and World Bank development projects.

The data for the paper is the result of a large-scale data digitization exercise. I digitized for the first time the universe of personnel records of PAS civil servants, in Punjab, from 1983-2013, which was combined with a publicly observable measure of merit (i.e. juniors’ recruitment exam ranking published in newspapers) as well as a measure of merit that is only privately observable to the seniors (i.e. juniors’ tax collection performance). Below are the three key results from this paper.

Result 1: Discretionary promotions are meritocratic

Contrary to the conventional wisdom on bureaucracies, results show that discretionary promotion of junior bureaucrats by their seniors is meritocratic. With an above average increase in the promotion power of the seniors, the junior who is a top 10% exam performer is 30% more likely to get promoted than the mid 80% exam performers.

On the other hand, the bottom 10% exam performer is 18% less likely to be promoted than the mid 80%. The effect on the top and the bottom 10% exam performers is statistically significantly different from each other. Both the effects are nearly the same as the mean of promotions and thus are economically significant as well.

Result 2: Direct self-interest of the senior results in meritocratic promotions

Since the type of junior bureaucrats promoted in the senior’s team has a direct effect on the senior’s own performance, an above average increase in the promotion power of seniors leads to nearly four times higher probability, relative to the base category, for the top 10% exam performers to start working in the senior’s team and be promoted there. Results reverse for the bottom 10% exam performers.

The effect is larger for the senior’s own team versus teams of others, suggesting that direct self-interest of the senior has an important role to play in the meritocracy of promotions.

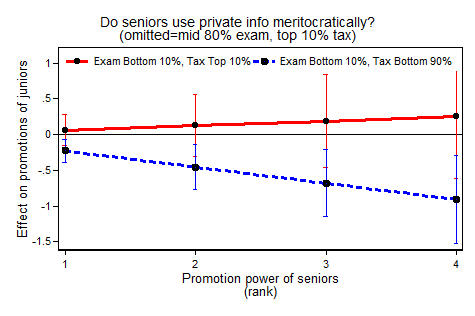

Result 3: Seniors use their private information on juniors meritocratically

With increases in the promotion power of seniors, those juniors that are top 10% exam performers, but not top 10% tax collectors, are three times less likely to be promoted than those that are star performers in both dimensions. More importantly, those juniors that are bottom 10% exam performers but top 10% tax collectors, have a two times higher probability of being promoted than those who are bottom in both dimensions.

Taken together these results suggest that there is value from allowing discretion in bureaucracies. Seniors are not just able to decipher the hidden lemons from the true stars but also the hidden gems from those that are bottom in both dimensions.

What does this mean for policy?

This study speaks to the debates on rules vs. discretion in organizations and allows a lens into the information cost of rigid rules that take away discretion. It shows that in contrast to conventional wisdom on bureaucracies, in fact, a case can be made to increase autonomy rather than reducing it.

While the effects of allowing discretion might not have a universal answer, the results in the paper highlight that we can design specific organizational systems that ensure that discretion results in meritocracy. For instance, one way would be to allow senior colleagues discretion in not just promotions but also in the choice of their teams. This could result in the seniors exercising discretion meritocratically in their own self-interest.

What the unique setting of the paper allows us to learn is more general than just public-sector bureaucracies. There is decentralized information relevant for personnel management decisions in most organizations, both public and private. Allowing discretion of promotions and choice of teams to senior workers can also help private organizations use local information and select the best performers for promotion.

Finally, it is easy to see why, despite meritocracy, there can be a feeling that “it is not what you know but who you know that matters” since only those high performers that have powerful seniors get promoted more, it leaves behind those high performers who have less powerful seniors. One way around this is to ensure job rotation of juniors, so that powerful seniors have information on a larger pool of juniors and can promote meritocratically from within the larger pool.

Shan Aman-Rana is on leave from civil services in Pakistan and is currently a PhD Economics candidate at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Email: s.aman-rana@lse.ac.uk

www.shanamanrana.com

Join the Conversation