Agent de santé sur fond d'écran numérique

Agent de santé sur fond d'écran numérique

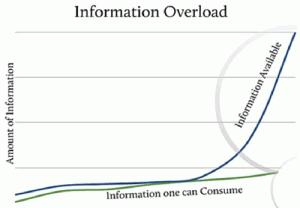

As governments work to blunt the health and economic impacts of COVID-19, the proliferation of data of various quality and misinformation (or an “infodemic”) that accompanies the pandemic makes government response and decision making even more difficult. But does that mean that governments are doomed to drown in the data deluge? Not necessarily.

Governments can better navigate and utilize data for more strategic and timely decisions if they are equipped with the appropriate technical and behavioral competencies. Leveraging data to respond to challenges – from the allocation of medical resources to economic recovery policies – should be an important pillar of a government’s strategy to fight the pandemic. How governments make use of this data can help with disaster risk management and meet their development objectives.

The need for better digital data for decision-making is often invoked to address a range of pressing national and local public as action challenges, whether for gauging the depth of the shock to prioritizing where investments should go, including in data itself. COVID-19 has shown that policy makers at various level of governments can simultaneously face a dearth and deluge of data. Traditional statistical and administrative data may not be agile enough to respond to the pressing and rapidly evolving response, recovery, and longer-term resilience demands of the crisis.

Just how much information can you swallow without getting sick

Source: Forbes

1. Salience: Users should perceive the new information or insights conveyed by the system as relevant, with a clear and significant bearing on issues that are important for the decision maker. It is important to go beyond assumptions and understand the variety of incentives that guide decision makers' actions. But to paraphrase the late Steve Jobs, just asking customers what they want is not always the direct road to getting a product that resonates. Finding salience in information is a mix of bringing something new to the table, as well as imagining a world beyond business as usual. For example, rapid mobile-based surveys can help collect real-time data on whether containment policies are being adhered to, or which economic responses are working on the ground.

2. Non-redundant: Decision makers are unlikely to use a system that provides information they already know; the data should provide new information or insights. A dashboard showing statistics that everybody knows already (e.g., a government dashboard when everyone uses Google, or that the impact of COVID-19 is significant) is unlikely to attract decision makers’ attention. Bringing out the distributional relevance of who is impacted will matter more. The key is to show that new data presents something different, or points out that conventional data sources are flawed or out of date. The biggest examples of value may come in combining data through more accessible and curated analytics and visualization, for example by working to show local hot spots where recovery is at risk.

3. Credible and dynamic source data: The most beautiful dashboard visualization design based on bad or incomplete data is akin to putting lipstick on a pig. Establishing a dashboard on data that needs to be manually collated in the future is never likely to be sustainable. Digital data is never likely to be perfect at the outset. Many financial management or e-procurement systems still do not cover all transactions. Data systems are just the containers for data, but it is ultimately an understanding of the actual data properties and content that matter. The crisis can be an opportunity to move beyond business as usual in terms of how data is shared, including through “live” digital mechanisms such as Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) and some use of AI decision support tools.

4. Actionable: The data should inform what is specifically within the reach of the decision maker. For example, a decision maker with no budget or legal powers is unlikely to use a system whose insights are mainly budget increases or legal reforms. Digital data for impact means not just feeding the next research paper, but finding ways to empower frontline actors – including mayors, governors, as well as central authorities – with better and more sustained ways to meet the COVID-19 challenges.

The COVID-19 crisis has created vast amounts of digital data for governments, but also highlights just how fragmented and challenging making decisions based on this data can be. Using the criteria or salience, non-redundancy, content, and actionality are critical in giving greater sense and meaning to the ever-turbulent sea of new data, especially in times of crisis and beyond.

Join the Conversation