Increasing role of governments

Increasing role of governments

The crises over the last few years, from the Covid-19 pandemic to the current energy crisis that resulted from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, has brought pressure on governments to respond quickly to the increasing needs of their people. In the process, it has brought focus on the need for good governance in both preparing for a crisis and responding to it.

The Covid-19 pandemic has changed the way governments operate, especially in providing stability and responding to the increasing demands for services from their citizens. This increased scope of government corresponds to an increased need for good governance. However, several questions arise: How can this enhanced government activity be supported financially: through higher taxes or larger deficits? Also, how does the government decide that the public danger is over and if it can scale back its support? What governance mechanisms are needed to ensure that public money is not wasted or, worse, feeding corruption? This blog attempts to answer the last question.

Previous Crises

Increased pressures for governments’ interventions started well before the Covid-19 pandemic; in fact, ever since the 2007-2008 Global Financial Crisis. Large countercyclical fiscal policies were put in place (for the first time in decades, the IMF recommended a 2 percent global fiscal expansion) and governments introduced monetary policies to reduce spreads in dysfunctional markets. Increased government interventions included measures to support the banking system, either through subsidies, outright temporary nationalization of banking institutions, nationalization of insurance companies (for example, the acquisition by the U.S. Government of majority stakes in AIG and GMAC), capitalization of too-big-to-fail companies, or other financial measures by central banks (for example, the Central Bank of Nigeria in 2008 controlling approximately 60 percent of the stocks on the Nigerian stock exchange after granting about $10 billion in margin loans).

During the Covid-19 crisis, governments were again pressured for greater intervention when fast delivery was needed for household and business subsidies or to support the health sector (for example, a 13th salary in Brazil and cash to families in India; moratoriums on insolvency in Italy; the creation of an NGN50 billion credit facility in Nigeria for affected SMEs; free vaccine access in the U.S. and new hospitals in China). Public procurement was placed front and center. For the first time, governments were procuring goods that did not yet exist, had no guarantee of working once produced, and for prices that had not been fixed yet.

In 2022 governments are confronted with yet another crisis. The war in Ukraine has had a huge impact on the energy sector, as well as on the prices of certain commodities such as grains and fertilizers. Governments have provided support through subsidies for certain groups of consumers, capping energy prices, or getting involved in the production and transmission of energy through state-owned enterprises (SOEs). OECD countries have combined price and income-support policies. The Indian and Peruvian governments have focused on tax cuts for petrol and diesel, while Brazilian authorities have capped prices. In Ecuador, granted subsidies on fuel and fertilizers are worth 0.8 percent of GDP.

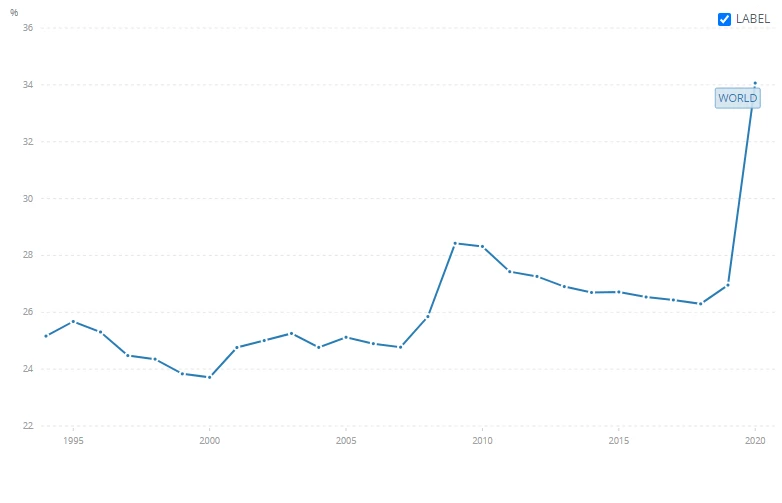

These changes in government activity are reflected in the national account statistics as well. Worldwide, the share of public expenditure to GDP has jumped from 25.9 percent in 2008 to 34.1 percent in 2020 and is likely to rise again in 2022 (Figure 1). This increase can be seen across regions: 5.9 percentage points increase between 2008 and 2020 in the European Union, and 5.5 percentage points in the decade between 2010 and 2020 in Latin America.

Figure 1. Expense as a percentage of GDP from 1994-2020

Source: International Monetary Fund, Government Finance Statistics Yearbook and data files, and World Bank and OECD GDP estimates.

Governance During Crises

The experience from previous crises tells us that three main channels of governance require strengthening when governments are faced with increased demands from their citizens. First, increased public spending necessitates a more efficient system of public procurement, to expeditiously process the larger flow of projects. Some governments impose temporary stops on standard procurement procedures, to the detriment of transparency and anti-corruption efforts. Instead, more discretion can be given to regulators in countries with high human capital and proven internal organizational checks and balances.

Secondly, new subsidy schemes require specific disclosures and/or auditing, to ensure that the money achieves its intended purpose and is not misspent. In normal times, these disclosures and audits of public sector activities may take years to complete, if even required at all. In crises, new technology may be used to complete them quickly. Subsidies present a challenge similar to that of public procurement, where in times of crises there is a natural tension between speed and the possibility of corruption, inefficiency, and abuse.

Lastly, larger state ownership of productive assets, for example in the healthcare or energy sectors, means that SOE governance requires new attention. There is often a tension in state-owned enterprises between serving a public-policy function and running an efficient business. During crisis, the former takes priority. Public policies however react quickly to a developing crisis—for example, when buying ventilators or supporting vaccines research—and hence boards of SOEs must be staffed with professionals able to discern such trends.

Since most countries at this stage do not have the capacity to shift towards public-private partnerships (PPPs) models, (for example, recent failures in large privatization efforts in Angola, Ethiopia or Zimbabwe), the focus should be on improving SOE governance. However, this is further challenging due to lower salary and financial incentive structures that are generally not competitive with the private sector. Such structures must be updated while, at the same time, creating transparent hiring protocols.

The World Bank has vast experience working with governments to overcome deficiencies in public sector governance. Crises are motivators to further this work by pinpointing the weak links in the chain of public service delivery and providing solutions. The main lessons, however, can be drawn from academia. The technology of economic crises forecasting is evolving constantly and with it our powers to predict future crises. This makes it possible to finetune governance mechanisms before the frenzy that erupts during crises abatements. Such improvements are best done in normal times in preparation for the difficulties ahead.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the first of a series of blogs on the governance-related challenges emerging from the recent crises.

Join the Conversation