Photo by KC Nwakalor for USAID / Digital Development Communications

Photo by KC Nwakalor for USAID / Digital Development Communications

In its commitment to more openness, the Nigerian government on December 9, 2019, launched a new financial transparency policy and web portal to provide the public with greater insight into government expenditures. The policy sets minimum financial reporting requirements and regular deadlines for over 800 government Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs). All MDAs are also required to promptly respond to additional information requests beyond what is published.

The policy and portal combination could be instrumental in allowing auditors, government watchdogs, NGOs, and ordinary citizens to promptly assess how government invests and spends public resources. It might also prove to be a game changer in Nigeria’s quest to improve government transparency and an important milestone in the region’s long-standing struggle against corruption.

According to a 2019 Afrobarometer survey in 35 African countries, 55% considered corruption to be on the rise in 2019, and one in four had to pay a bribe to access basic services in the same year. Nigeria itself has consistently ranked low in Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index, and as recently as 2019 the US State Department declared that the country did not meet its fiscal transparency standards.

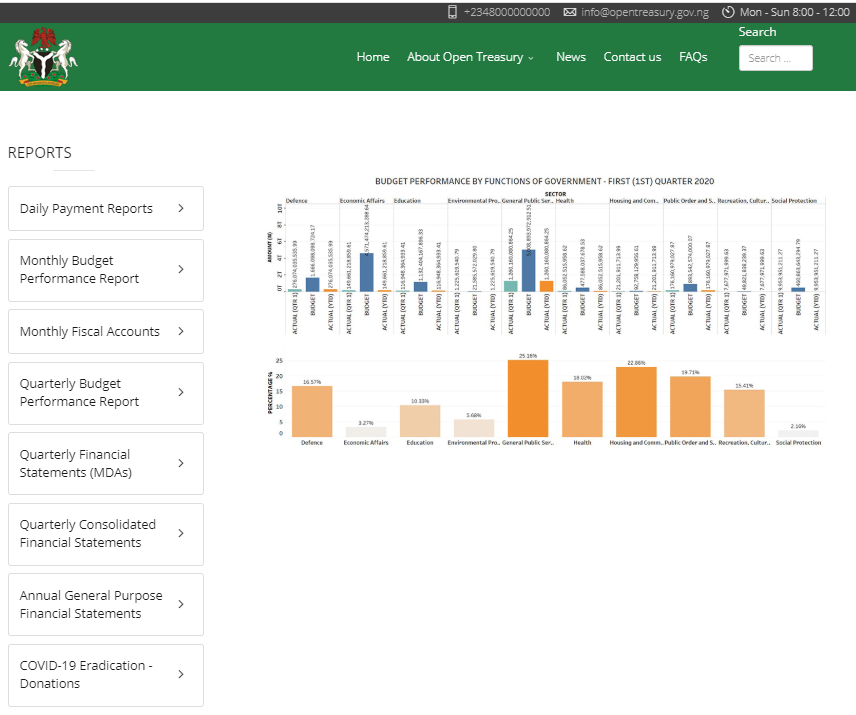

Screenshot of Nigeria's new Open Treasury Portal

Developed entirely with in-house expertise, the reforms dovetail with the country’s involvement in regional and global accountability initiatives such as the Open Data for Africa initiative and the Open Government Partnership. Ken Ife, Visiting Professor at the Centre for the Study of Leadership and Complex Military Operations, described the policy as a seismic shift. “There is nothing like it. It actually says to the people ‘you want transparency, here is transparency’.”

In addition to annual and quarterly financial statements, monthly fiscal accounts, and monthly budget performance reports, the Transparency Policy requires daily publication of a treasury statement and details of all payments made above a threshold of US$27,700 for the federal treasury and US$13,850 for MDAs. All reports are published on the easily searchable “Open Treasury” portal, a one-stop shop for financial transparency. To oversee the policy’s proper implementation, a Compliance and Quality Assurance Committee has been established that includes members of anti-corruption bodies and other civil society organizations.

The federal treasury, for its part, has been regularly posting daily payment reports and budget performance reports. Many MDAs have been uploading monthly and quarterly reports, yet gaps remain between the policy’s requirements and what is actually being uploaded on a daily basis—the initiative, after all, is just a few months old so remains a work in progress. Despite not yet reaching full compliance, the level of transparency already achieved is impressive when placed in a context where more than 300 entities failed to provide audited financial statements to Nigeria's Supreme Audit Institution for review by the legislature.

The rigorous self-reporting requirements are underpinned and made feasible by the World Bank-funded Government Integrated Financial Information System (GIFMIS), an automated cross-governmental accounting system. Other recent reforms include the implementation of the Integrated Personnel and Payroll System, a whistle-blower policy, and the adoption of International Public Sector Accounting Standards and the Treasury Single Account.

“Through this initiative, the foundation for a strong partnership against corruption will be laid,” said President Buhari at the launch. “While publication of public financial management information will remain a key hallmark of this administration, the general public and the civil society are enjoined to take advantage of this policy and hold public officials to account.”

With billions of dollars to support Nigeria’s COVID-19 response anticipated from multilateral financial institutions over the coming months, the portal has the potential to provide real-time insight into actual expenditures incurred against COVID-19 budget allocations. This could help ensure that funds intended for public good are not illicitly diverted for private gain, which, in the face of this health and economic crisis, could be the difference between a livelihood, or even a life, lost. The largest economy in Africa can thus provide a model for other countries looking to bolster public accountability in this fraught time.

Join the Conversation