Preference for large families continues to be a major factor determining levels of fertility in Sub-Saharan Africa. Recent data from DHS demonstrate reasons why men and women prefer and choose to have large families. Though factors influencing women’s decisions are complex and vary from one society to another, there are also similarities.

Culture, religious beliefs, gender relations and low child survival rates - all play a critical role in very personal decisions about reproduction and hence overall fertility levels and trends. It is not always about ‘supply side’ factors or economic barriers- that is availability of family planning services - the number of children women have is a very personal decision.

Various factors determine the number of children families have including: i) Desire for large families – own desires, family desires, social norms (including old age security); ii) Prevalent child mortality – replacement and hoarding/insurance; iii) Knowledge – knowledge on the reasons to use family planning, available options, side effects and mitigation measures, available services and locations, and costs; and (iv) Access to quality family planning services.

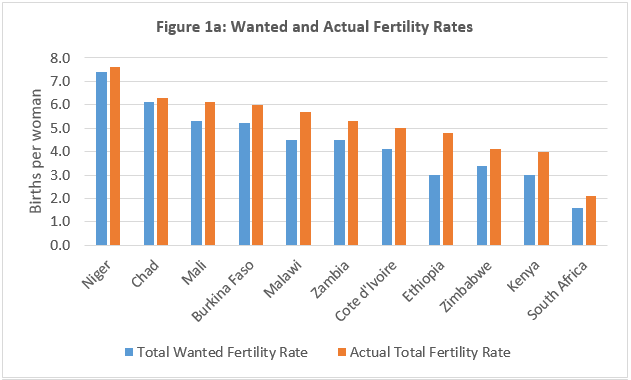

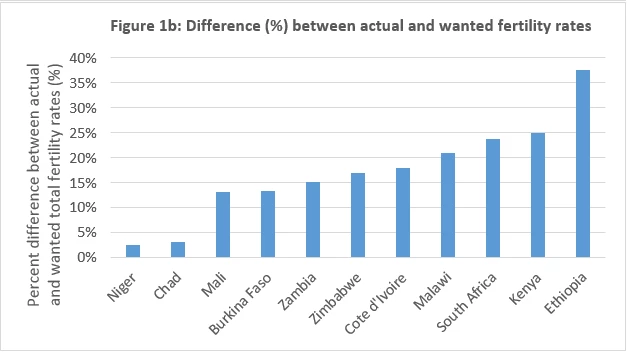

The Sahel Region has one of the highest levels of desired fertility in sub-Sahara Africa. DHS data show that on average, the majority of women want to have more than five children; the desired number of children is more than eight in Chad and Niger. Furthermore, the gap between actual and wanted fertility varies substantially across sub-Saharan Africa (Figure 1a). In countries such as Niger, Chad, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Zambia, the difference is less than 15%, indicating that demand-side barriers may be a bigger challenge than supply-side barriers (Figure 1b). In Niger and Chad, the difference is about 3%.

Children are also a form of safety net as aging parents struggle to support themselves in the absence of retirement savings and pension funds. The Sahel analysis also demonstrated that the position of women in society and unequal gender relations within a union are key factors influencing whether women can access key reproductive health services, including family planning. Men’s desire for large families as well as cultural and religious interpretations opposing limiting family size were also cited as reasons for large family sizes prevailing. For example, 21% of women in Niger reported that needing husband’s permission created problems in seeking care for reproductive health. [2] Women cited fear of disapproval and stigmatization if they went against societal norms. Moreover, a large number of children increases the probability that a few will survive to adulthood, serving as a form insurance in high child mortality societies.

In addition to a desire for large families and considerations for child survival, there is the issue of knowledge. While knowledge of a modern contraceptive method is relatively high (and even nearly universal in some countries in Sub-Saharan Africa), knowledge is limited in other areas. Knowledge of the fertile period, reproduction and sexuality; benefits of using family planning; various method options; possible side effects associated with each method and mitigation measures; available services and locations; and costs tend to be limited. For example, in Niger in 2012, while 90% of women knew of a modern method, only 40% of women reported being informed of possible side effects of methods. [3] Furthermore, only 35% reported being informed of what to do in case side effects occur and 57% reported being informed of an alternative method. In a survey conducted in The Gambia, nearly 20% of women in a rural region reported that they did not know where to get contraceptives. [4] Limited access to comprehensive quality family planning services – appropriate counseling, information, commodities, and technical capacity to deliver them – hinders uptake of family planning. Financial, geographic and sociocultural factors are often substantial demand-side barriers to the utilization of family planning and decline of fertility.

Policies that address women’s reproductive health needs must take these demand-side barriers into account. In many cases, such barriers are difficult to tackle as they involve the realm of faith and very personal choices shaped by cultures and traditions that took generations to evolve. They present a tough challenge in efforts to open up the poverty reduction and economic growth possibilities linked to the demographic dividend. Promising strategies that have been employed successfully at scale in other regions (e.g. South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Middle East) include [5]:

- social and behavior change communication targeting and involving various relevant actors to address cultural, social, religious and traditional norms;

- community-based distribution of information and services on family planning to overcome gender, mobility and information barriers;

- community-based distribution and integrated delivery of child health and nutrition services to improve child survival and address the replacement/insurance pathways to fertility decisions;

- training of health care workers to provide better information and services to overcome the knowledge barrier; and

- girls’ education for longer term shifts in preferences and ability to act on preferences.

Evidence and country experiences suggest that a combination of demand- and supply-side interventions are necessary to overcome entrenched and complex demand-side barriers in the transition to smaller families, poverty reduction and economic growth. The opportunity for widespread change in sub-Saharan Africa is possible with policies that take these lessons into account and are well-implemented.

Related links:

Blog: Optimism about Africa’s demographic dividend

Publication: Africa's Demographic Transition : Dividend or Disaster?

Follow the World Bank health team on Twitter: @WBG_Health

Join the Conversation