A new paper attempts to comprehensively gauge how government health spending has fared in developing countries over the past three years. Copyright: World Bank Group

A new paper attempts to comprehensively gauge how government health spending has fared in developing countries over the past three years. Copyright: World Bank Group

Over the past three years, the world has faced shocks in swift succession. Starting in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic claimed millions of lives and nearly brought the global economy to a halt. Two years later, the Russian invasion of Ukraine caused abrupt price increases for energy, food and other commodities that intensified inflationary pressues already building up. When central banks responded by increasing interest rates, the costs of debt servicing and access to new finance mounted, and financial systems came under stress.

As a result of these successive upheavals, recovery from the global recession has been slow and uneven. Trends in fiscal space have also diverged: government spending has expanded in some countries, while stagnating or contracting in others. Many low- and middle-income countries, in particular, have struggled to return to pre-COVID economic growth and government spending trajectories.

Public investments in health

The new paper of the Double Shock, Double Recovery series, “Health Financing in a Time of Global Shocks,” is a first attempt to comprehensively gauge how government health spending has fared in developing countries over the past three years. Throughout this challenging period, public investments in health have been critical to manage shocks and buffer their effects on human capital, most importantly, by controlling the COVID-19 pandemic.

The study included 78 developing countries. The analysis focused on central government spending on health, considering its levels as well as its shares in general government spending. It examined change relative to prepandemic levels, that is, in 2019, and offers comparisons to projections based on pre-pandemic trends between 2017 and 2019. The study drew on data from nearly 2,000 budget documents, both data and documents all made available to facilitate further research.

We found a complex pattern of central government spending on health, with trends that simultaneously hold promise, but also raise concerns. After an initial strong response to the pandemic, health spending is for many governments no longer a priority – putting at risk global health security and progress toward the health-related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Robustness checks demonstrated that the general trends reported in our study hold when considering other components of government spending on health, including obligatory social health insurance contributions, special funds, and sub-national government spending.

A strong advance

During the first two years of the pandemic, real central government spending on health generally soared. In 2020, it grew in per capita terms on average across all countries approximately 21 percent, and in 2021, it stood at 25 percent above 2019 levels. This surge pattern was common to all country income groups and two-thirds of all study countries (56 of 78). In the group of 56 countries with a positive response, average per capita central government health spending rose in 2021 to almost 40 percent over 2019.

The strong advances over the first two years of the pandemic were primarily driven by governments prioritizing health in their spending. Growth in general government expenditure played a lesser role. By 2021, the central health share in general government spending had grown 17 percent over 2019, far outpacing the six percent growth in general government spending.

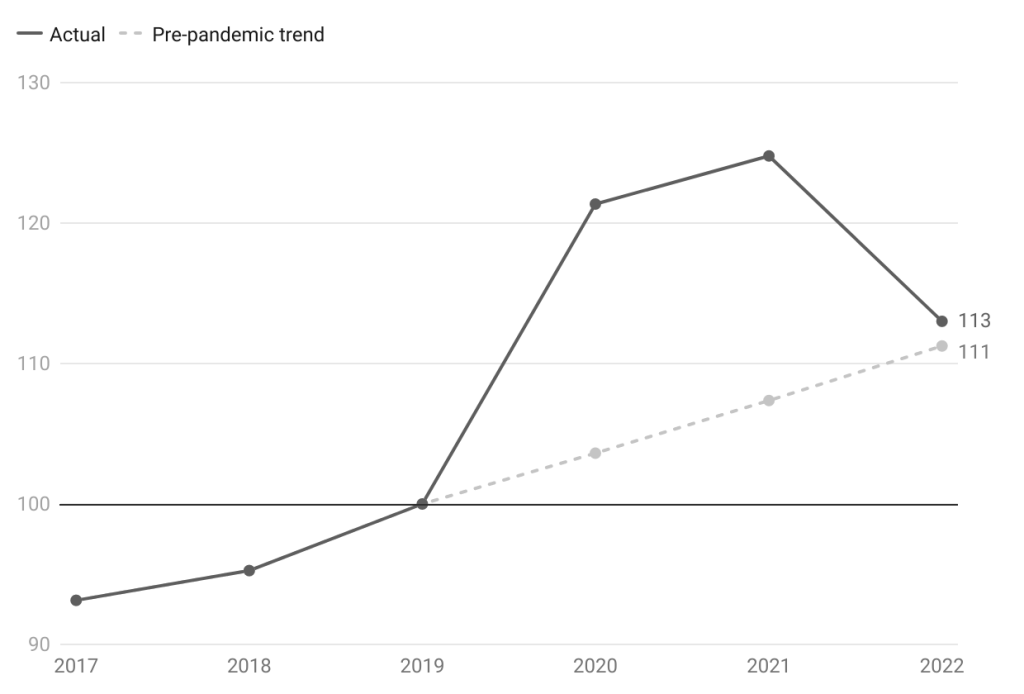

Figure 1. Average real per capita central government health spending, actual and pre-pandemic trend, 2017-22 (2019 = 100)

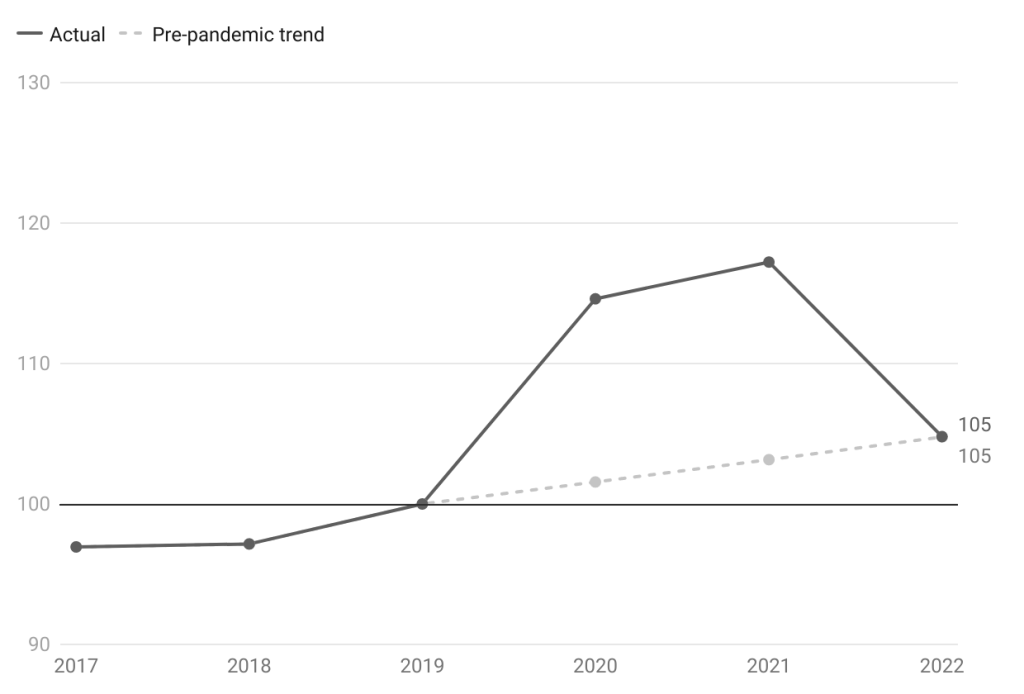

Figure 2. Average central government health spending as a share of general government spending, actual and pre-pandemic trend, 2017-22 (2019 = 100)

An early retreat

The initial strong advance in real per capita central government health spending lost momentum in the third year of the pandemic, turning into an early retreat. On average, it contracted, from its peak of 25 percent to only 13 percent above the 2019 level and close to its pre-pandemic trajectory (Figure 1). The 2022 spending drop was sharper in low-income countries and upper middle-income countries that receive funding from the International Development Association (IDA)—the World Bank’s fund for the poorest countries.

The reversal was even starker in the priority that governments gave to health. On average, the central health share in general government spending tumbled, from its maximum of 17 percent to only 5 percent above the 2019 baseline, falling back to its pre-pandemic trajectory (Figure 2) Again, the drop was more pronounced in low-income and upper middle-income countries that receive funding from IDA. In nearly half the countries (37 of 78), the central health share of general government spending in 2022 fell below 2019 levels. In turn, it was no longer the prioritization of health, but growth in general government spending that primarily helped bolster 2022 central government health spending above 2019 levels.

Choosing a different path

The rapid decline of real central government health spending came at a time when rapidly rising energy and food prices as well as debt service costs had started to impose new spending obligations on governments.

Yet, it may have been a costly and risky retreat. While central government spending on health receded, the omicron variant caused another wave of COVID-19 infections and death worldwide in early 2022. As countries started to relax public health measures later in the year, many health systems struggled to cope with the backlog of non-COVID- health services caused by earlier service disruptions.

Also, the stark reversal in the priority given to health in government spending does not bode well for global health security, and progress toward the health-related SDGs. In many developing countries, government health spending had been insufficient for meaningful progress toward stronger health systems prior to the pandemic, while today, for many of them, the macroeconomic outlook remains concerning with limited capacity to increase government spending.

Government spending on health, however, does not have to fall even when economies and fiscal space shrink, as seen during the global financial crisis of 2008-09. Rapid action of governments will be necessary in many developing countries to reverse the latest trends and secure the prioritization of health in government spending to put their countries and the world on a new, pandemic proof and sustainable development trajectory.

Join the Conversation