As we have been arguing for a while, it is important to carefully measure both the benefits and the costs of the interventions we recommend, and this is even more important during the COVID-19 pandemic. Confronted with a deadly virus and school closures, economic recession, and widening inequalities, policymakers and educators all over the world are feeling the pressure to make rapid decisions to reallocate education resources to mitigate learning loss and to protect their budgets from other sectors of the economy that are also suffering.

In response to system-wide school closures, many countries swiftly rolled out different types of remote learning platforms on a large scale, with the purpose of replacing in-person instruction with educational programs broadcast on TV or radio, online learning, or text- or phone-based instruction. Likewise, many researchers are assessing the effectiveness of these interventions by randomizing different encouragements or nudges for students and families to engage with the remote learning services, as well as direct delivery of content, such as instructional phone calls from teachers. Through its COVID-19 Emergency window, for example, the Strategic Impact Evaluation Fund is supporting these kinds of evaluations.

Conceptually nudges might seem so simple and cheap you might be tempted to make (up) a back-of-the-envelope estimate of their costs or just declare them to be affordable or cost-effective. But it is important to verify this with a proper costing exercise.

Cost here refers to the opportunity cost of all the resources and efforts required to implement the intervention, regardless who pays for it. For example, the encouragements or nudges are expected to increase parents’ engagement in their children’s learning, so the opportunity cost of the additional time spent by parents should be counted as part of the cost of the intervention, even though it is not charged to the funder of the intervention and parents “pay” by sacrificing potential income. Students’ behavior may also change since they are likely to spend more time studying. However, we only recommend pricing out the time of the students who have reached the legal working age (child labor does exist in some countries, but it is very difficult to collect accurate information on the number of their working hours and their pay rate). Another example would be the reallocation of teachers’ time due to the switch from in-person instruction to remote learning. Suppose teachers provide phone-instruction to individual students twice a week, with each call lasting 20 minutes. Although teachers do not receive extra compensation for the phone-instruction, we still need to carve out the percentage of their time that can be attributed to this intervention and price it out as part of the cost. All these resources, no matter who pays for them or whether they are cash or in-kind, are essential for the replication of the intervention, and therefore should be accounted for in the cost analysis.

We developed a template and costing model for our COVID-19 teams to get started on conducting a rigorous cost analysis, which may be useful for other teams that want to cost out remote learning services. Here’s how it works.

The first two tabs of the spreadsheet (Introduction and Setup) require a user to enter basic information about their program, experimental design, and estimated impacts (users not conducting an evaluation can just substitute the word intervention for treatment).

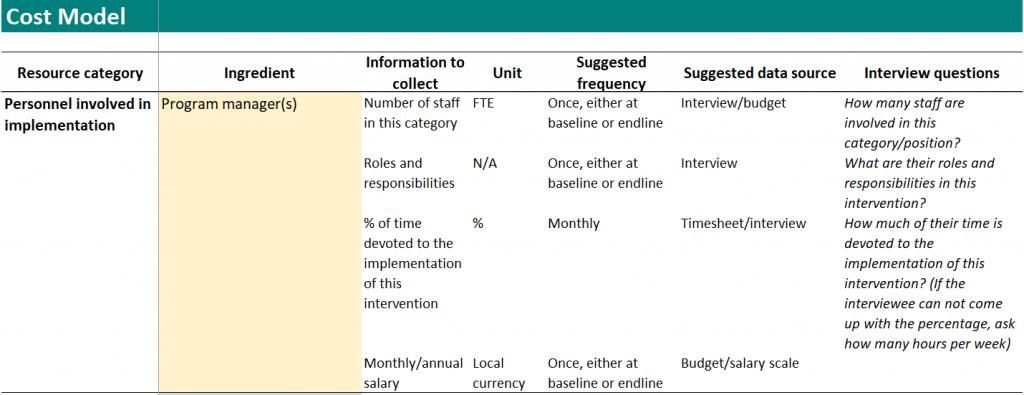

The next tab, the most important, presents a cost model and data collection plan, which is something you ideally work on before the intervention starts. The cost model is meant to be an exhaustive list of all the activities and ingredients (such as staff, facilities, subsidies, curricular content, and parental involvement) required to implement an intervention. Here we list a cost model that includes the union of all activities and ingredients of five of the interventions that are being implemented in Bangladesh, Ghana, Guatemala, Pakistan and Sierra Leone and will be evaluated in our COVID-19 window, but the model will need modification for different interventions and different contexts. The data collection plan helps identify how you are going to find this information. A user would list the units each ingredient should be measured in, the frequency of measurement, potential data sources, and any interview questions that may be required to elicit information (yes, cost capture requires talking to people, not just collecting spreadsheets). We have made suggestions here, but again the cell content should be customized to context (a screenshot of the row on the program manager’s time is below).

In the next tab (data entry), users should enter the data they collect based on the cost model and data collection plan, and fields in this tab include the quantity of each ingredient used, any allocations that might need to be made across interventions in case shared inputs are involved (e.g. a supervisor is assigned to supervise multiple interventions), and the price associated with each unit of each ingredient (screenshot below). We have inserted a monthly line for personnel-related ingredients (as they tend to be expensive and may be involved in different intensities throughout the year) and just one line for other types of ingredients, but if this doesn’t reflect the time pattern of expenditures, then this should be adjusted. We have also inserted optional columns to document whether costs are start-up or recurrent and the funding source for each ingredient, in case it would be useful to break down costs by these characteristics.

The results tab takes what has been entered in previous tabs to provide estimates of the total cost of each intervention, the cost per targeted participant (to go with ITT estimates of impact), and the cost per treated participant (to go with TOT estimates of impact), as well as the corresponding cost-effectiveness ratios. Since the linearization involved with cost-effectiveness ratios can be misleading, we’ve also included a graph that simply plots effects against unit costs, in case a user or policymaker is interested in seeing how much additional impact can (or cannot) be gained from investing more.

The template also includes an illustrative example that provides guidance on how to use the tool. Based on a hypothetical example of an SMS-based intervention for remote learning in Afghanistan, we demonstrate how to identify the ingredients; set up the cost data collection plan; collect data through budgets, interviews, and phone surveys; calculate the cost estimates; and interpret the results. The narrative of the example and notes describe what the process would look like, whom to talk to in the field, how to implement a Plan B when Plan A does not work out, and what the built-in formulas mean. The last two tabs are the time-series data of the consumer price index and official exchange rate for all countries, extracted from World DataBank. You may use these datasets to adjust for inflation when the prices of all ingredients are not expressed in the same year or to transfer local currency to dollars, or vice versa.

The final numbers that come out of this exercise can be useful for economic evaluation of programs or making budget requests. But these are not the only uses of cost data. Since cost capture entails an exhaustive list of all activities and ingredients, as well as their intensity of use, it is also useful for planning exactly what resources would be needed to encourage take-up of remote learning services. Usually when describing interventions in impact evaluations, researchers tend to focus on what they perceive to be the intervention (sending SMS messages or interactive voice recordings), but policymakers typically want to know much more than this. They request guidance on how they should implement an intervention - if they are going to need someone to put in 35 hours of supervision time per week or just 5 or if they are going to require staff time from multiple departments, as getting these set up can require substantial planning (and requesting and re-requesting). Cost data can give them this information.

While we created this costing template for specific evaluations testing the impact of encouraging engagement in remote learning, we hope it will be useful for others trying to get started on costing their interventions. Let us know how it goes.

Join the Conversation