Imagen de la campaña #MujeresUruguay del Banco Mundial

Imagen de la campaña #MujeresUruguay del Banco Mundial

Why do some households pay more taxes or receive more government transfers than others? It may be because many public policy decisions have distinct effects on different population groups. Still, policy does not always consider key factors such as the challenges that people face in society and the economy because of their gender. This has consequences for public spending efficiency, poverty and inequality.

Gender gaps in labor market participation, wages, occupation and time use, for example, influence the burden of direct taxes (such as personal income tax) that women actually pay, compared with men. Although many studies have examined the incidence of tax collection and public spending on society, few have included the gender dimension in the analysis. This omission limits the possibility of understanding what role household composition plays in tax and spending decisions.

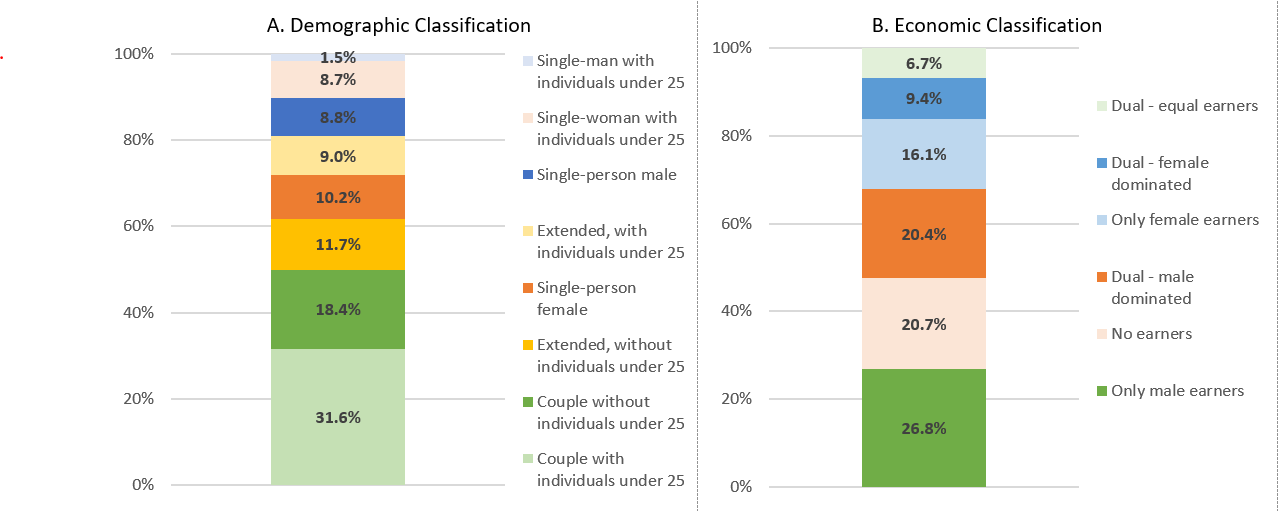

Let's look at the case of Uruguay: The most prevalent type of household is comprised of a couple plus individuals (children or others) under 25 years of age, followed by households of couples without children. Another common type is the single-person household, currently accounting for one in five households. Half of these households are made up of a single woman and the other half of a single man, although the characteristics of these two types of households differ. For example, 70 percent of female single-person households are comprised of a pensioner, compared with only 30 percent of male single-person households.

Unlike single-person households, single-parent households (where there is only one adult responsible for children under age 25) show important gender differences. The proportion of single-woman households with individuals under age 25 is considerably higher than that of men in this situation. These households are also more likely to be poor (21.2 percent) than both single-parent male households (9.2 percent) and households comprised of a couple with children under age 25 (9.1 percent).

Distribution of households

Note 1: In Panel A, female (male) single-parent households are those comprised of a female (male) and individuals under 25 years of age. Although this definition does not imply a direct kinship relationship between the household head and the minor, in 86.2 percent of cases, individuals under age 25 are children of the household head.

Note 2: In Panel B, households with predominately women’s (men’s) income are those in which women (men) contribute more than 55 percent of the total labor income of the household.

Note 3: Although more recent data exist, the study uses the 2017 Encuesta Continua de Hogares (ECH) given that it is the base year of the last fiscal incidence analysis available for Uruguay (Bucheli, Lara and Tuzman, 2020).

Uruguay: gender and equality

Uruguay has made substantial progress towards gender equality in recent years, but significant gaps persist. For example, women participate less in the labor market than men, despite being equally or better qualified.

Additionally, on average, women earn 20 percent to 30 percent less than men in similar jobs , are more likely to work in informal employment and less likely to be employers or business owners. Women also bear a greater burden of unpaid work, on which they spend 20 percent of their time (compared with 8 percent for men).

These gaps are well known and studied. However, with these statistics on the table, we may ask what impact fiscal reforms could have on households of different gender compositions.

To answer this question, the World Bank's Poverty and Equity team is conducting a study that, among other things, sheds light on the demographic and economic composition of households and their situation of vulnerability.

This study finds that men are the main source of household labor income in nearly half of Uruguayan households, while women are the main income providers in only a quarter of them. Households where men and women contribute equally to household income only account for 6.7 percent of the total, even though both sexes work in 36.4 percent of households in the country. Households where women are the main earners are more likely to be poor, and the lowest incidence of poverty occurs among households where both sexes contribute equally to household total labor income.

In households comprised of couples with children, when one member of the couple does not work, it is usually the woman. The gender gap in labor market participation is more than double in households with children than in those without children. Not only are women in an intimate relationship more likely to work if they do not have children, but they are also more likely to be the main source of household labor income. This suggests that women without children tend to work longer hours, have better-paying jobs, or earn higher wages than women with children.

Persisting gender inequalities, coupled with the country’s demography, create the bases on which policies act. Incorporating the gender perspective in fiscal incidence analysis would make it possible to address these issues and respond to key questions in public policy design, such as: What effects would a reallocation of public spending have? How can the efficiency of public spending and tax collection be improved without disproportionately affecting the most vulnerable households? We will try to find some answers in this study.

Join the Conversation