The COVID-19 pandemic has made traveling on public transport a faraway memory for many people in Buenos Aires. We’ve stopped putting credit on our transport payment cards, or even taken them out of our wallets altogether. Some people may prefer this. They’ve swapped the daily commute for the chance to sleep in a bit longer. But others may miss meeting strangers or listening to songs by unknown artists on their journeys.

The pandemic may have seriously restricted our use of public transport, but it still plays a crucial role in Buenos Aires. Buses are vital organs that ensure accessibility and connectivity, even in these exceptional times.

The Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires, known as AMBA for its acronym in Spanish, is densely populated. It is home to around one third of Argentina’s 45 million people and is responsible for about half of the national GDP.

These two factors have steered the development of the city, making it a center of innovation and growth thanks largely to a public transport system that allows people to move around cheaply and efficiently. Before the pandemic, 22 million trips were made in Buenos Aires, of which 60% were on the extensive bus, subway, and train systems.

COVID-19: A sudden, disruptive impact

COVID-19 has had a major impact on urban transport around the world. Given the ways in which the virus can be transmitted, large-scale public transport has been deemed risky because of the impossibility of complying with social distancing protocols (although recent evidence would suggest the contrary). In short, the high risk of contagion has directly affected public transport, pushing the sector into a deep crisis.

In Argentina, the use of public transport has been discouraged ever since the authorities enforced an economic lockdown on March 20. Trips have been restricted to people with travel permits (essential workers or those who need to travel in events of force majeure). Passengers are monitored daily to gauge the number of people who are making trips. The data show that use of public transport has been on the rise over the past few months. This has led to a new set of procedures to deal with the influx of people starting to use public transport again, putting discussions about public transport at the top of the policy agenda.

Mixed reaction at the heart of the system

The lockdown has cut demand for public transport. Total passenger traffic plunged by 90% in the first week of the lockdown, followed by a slow recovery as the days went by. The backbone of the AMBA transport network – the bus system – was hit particularly hard, and in a variety of ways. Before the pandemic, the system, one of the most extensive in the world, accounted for four out of the five trips made on public transport in AMBA.

In terms of supply, use of the bus network was first restricted to seated passengers. Fewer buses ran and with less frequency in the first three weeks of the pandemic before supply levels gradually returned to levels similar to those of the old normality. Even so, demand is still only 20% of pre-pandemic levels.

Even before the pandemic, the bus system was experiencing design issues, including a substantial overlapping of routes, a gradual decline in total passenger numbers, and a reliance on subsidies for almost two thirds of the flat-rate fare.

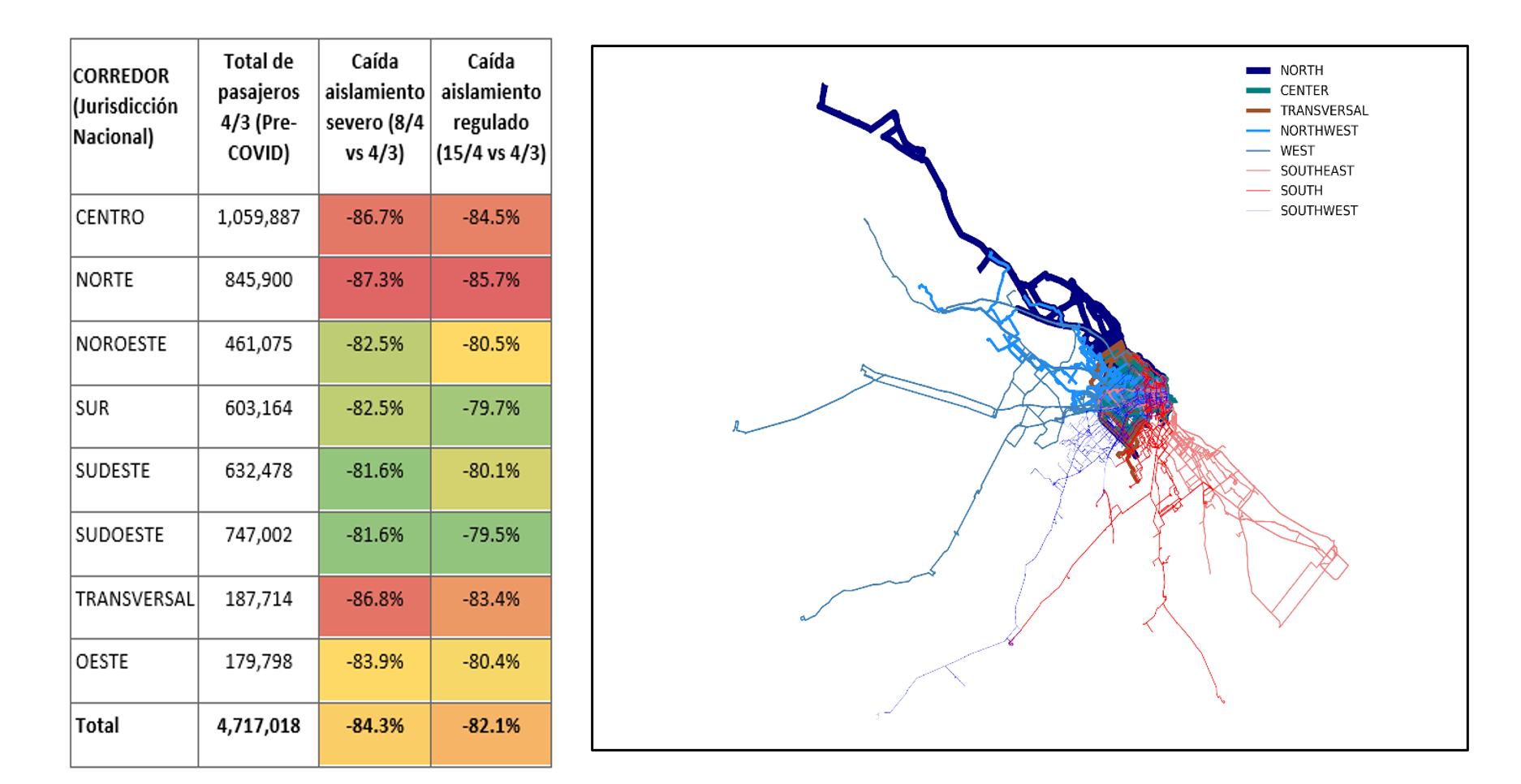

These inefficiencies were compounded by the existence of a homogeneous structure requiring all the lines to provide the same number of minimum services. This anomaly has generated very different outcomes for transit corridors and city lines, including a substantial level of spatial fragmentation, which has become more prominent since the pandemic began. For example, corridors in the north of AMBA have suffered the largest percentage declines in passenger numbers, while those in the south have lost fewer. This gap can be explained by the differences in the socioeconomic levels of the population (high in the north; lower in the south), and is closely linked with the opportunities for people to work from home and travel by car, and those who cannot.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, the productivity of the bus system, as measured by the total number of passengers transported per kilometer, has fallen 74%. These lower levels have had an economic impact. For example, a quadrupling of the technical fare, or the average cost of transporting a single passenger, has surged to 190 pesos (US$2.50), while the commercial rate has remained the same at 18 pesos (US$0.23). This shows how the new social distancing measures are affecting the efficiency and financial sustainability of public transport – and exposes the urgent need to find a balance between reducing transmission risks while also maintaining an adequate level of efficiency and sustainability.

The future must be metropolitan

In Buenos Aires, it is essential to regain people’s trust in public transport so that they will start using it again. We only have to look at the immediate consequences of the increased use of cars following the pandemic to understand why:

- Extremely high levels of congestion on a saturated road infrastructure;

- An increase in respiratory illnesses resulting from higher levels of toxic emissions;

- Increased road crash rates.

Although the city bus system has shown remarkable flexibility despite the regulatory changes, it needs new guidelines and incentives. Given the latent possibility of the system being forced to open and shut down intermittently, fresh policies are needed to respond to the requirements of a transport system that is increasingly leaning toward territorial fragmentation. These policies need to be accompanied by performance indicators to guide the operational framework of the system. Hybrid schemes can be tested to improve the connectivity of the most vulnerable groups, such as by expanding the use of buses-on-demand.

As AMBA is an indivisible epidemiological unit, the Metropolitan Transport Agency plays a key role in coordinating health control policies. The coronavirus pays no attention to administrative borders, which means that collaborative efforts by authorities in different zones are essential for addressing the complexity of the metropolis. Mobility is no exception.

The World Bank is supporting the Ministry of Transport’s efforts to strengthen the Metropolitan Transport Agency by drawing up a new urban mobility program for the AMBA. The aim is to improve the planning, management and operation of public transport and the introduction of new technological tools during the pandemic and in the subsequent stages of recovery and growth by increasing the resilience and efficiency of the system. This will make it possible to ensure connectivity and access to job opportunities and human development, even in extreme conditions like those we are living with today.

Join the Conversation