A farmer toils the soil in preparing produce

A farmer toils the soil in preparing produce

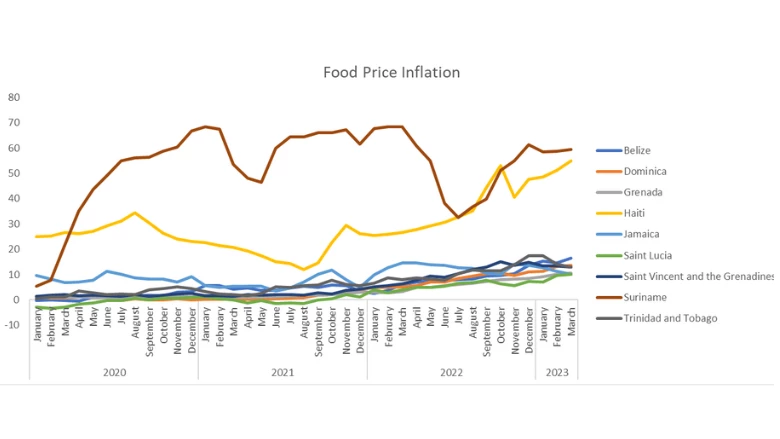

Across the Caribbean, farmers are worried about improving their production, and food shoppers are worried about the high cost of food prices. While international food prices have decreased recently, domestic food prices remain high in some parts of the Caribbean . This increase represents the region's primary driver of food insecurity, which is now a worrying phenomenon.

Today, food insecurity stands at its highest level in recent decades. In the English and Dutch-speaking Caribbean, around 43 percent of the population reported reduced food consumption in 2023, such as missing meals or reduced food intake. In Haiti, 58 percent of the population is classified as in a crisis or emergency stage of food insecurity.

The Caribbean is unique in having a generally high cost of food compared to other regions. The average cost of a healthy diet in Caribbean countries was estimated at USD 4.4 per person per day in 2021 in purchasing power parity terms, which is 42 percent higher than the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) average, 13 percent higher than the lower middle-income country average and 5 percent higher than the small island state average.

Several structural factors present a challenge to reducing food prices. The region is a net food importer, leaving it vulnerable to global price fluctuations. Traditionally, Caribbean agriculture focused on producing export commodities such as sugar and bananas. While Caribbean countries now aim to shift toward increased food production and diversification, domestic production volumes and productivity remain low. The cost and time related to intra-regional food trade are also high. Countries have reduced options for economies of scale due to small market size, leading to higher per-unit production, logistics, and transportation costs.

Agricultural policies place more burden on food consumers than producers. In the Caribbean, financial support provided to the agriculture sector is at a level like the Latin America region, but mostly benefits producers through market price support from trade protection policies for specific products. While this limits public sector expenditure support to farmers, price support represents an implicit tax on food consumers who pay higher domestic prices. Duties and taxes on food imports have also often served as a source of government revenue, even where they do not protect a domestic industry.

The Caribbean Community (CARICOM) has renewed its focus on boosting regional food production and intra-regional food trade. Following COVID-19-related disruptions to food supply, CARICOM leaders have expressed a desire to strengthen food production in the region. The CARICOM regional agenda for agriculture calls for increasing intra-regional trade, improving production/processing capacity, and improving the resilience of agricultural production to disaster and climate shocks.

What are the prospects for increasing the availability of affordable food, raising domestic production, and reducing vulnerability?

The following three policy options could be pursued:

- Reducing frictions in intra and inter-regional food trade to reduce transaction costs and address risk. There is potential to reduce the cost and time related to intra-regional food trade, particularly by building on the CARICOM regional trade framework. Investments in logistics infrastructure (transport and, in some cases, storage), trade facilitation and trade promotion, and market information systems should be prioritized to reduce transaction costs and build market linkages.

- Boosting food production without taxing consumers. Continental CARICOM members such as Guyana, Suriname, Belize, and larger islands such as Jamaica have the potential to significantly increase food production. Smaller island economies also have the potential to improve production of fruit and vegetables or livestock production that require a smaller land footprint. Many agro-processors and storage operators in the region are far below capacity, indicating the potential to scale up primary production. In this context, policy measures that support the development of more productive and competitive agricultural systems will be critical to sustain investments and production over the long term. Reassessing food policies to reduce the burden on consumers deserves another look.

- Improving resilience and reducing risk in the agri-food system. Adopting de-risking instruments and climate-smart Agriculture (CSA) practices and technologies can help accelerate the transformation of the Caribbean’s agri-food system. They will be critical for improving the sector's resilience. Risk management instruments such as partial credit guarantees, insurance, and contingency funds can reduce risks facing private capital and encourage more financing for agriculture. CSA offers “triple wins” by supporting higher productivity, building resilience, and lowering emissions. CSA examples particularly relevant to the Caribbean region include technologies to be used on-farm as well as along the agri-food value chain, such as heat and water-stress tolerant crops and livestock, conservation agriculture, agroforestry, solar-powered processing and cold chain systems, and low-carbon food packaging, etc.

The COP28 discussions in December 2023 allowed CARICOM and Caribbean countries to advocate for climate finance in the agriculture sector, enabling the region to safeguard globally important biodiversity while investing in more resilient and sustainable growth. Going forward, an opportunity exists for the World Bank to partner with countries to develop a regional food system that delivers for the Caribbean region and is more adaptable.

Stay updated with our weekly article

Related articles:

Join the Conversation