Designing Futures initiative reached about 250 students in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Designing Futures initiative reached about 250 students in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Economics Nobel prize 2019 laureate Esther Duflo emphasized the importance of hope for poverty alleviation: “A deficit of hope can be the source of a poverty trap, and, conversely, hope can fuel an exit from the poverty trap”.

What – you may ask – does this have to do with girls in Brazil and in Latin America as the title suggests? A lot.

Young women in Latin America and the Caribbean may be deprived of ‘hope’ due to poverty, lack of opportunities and gender norms that restrict their options. They may feel unable to take control over their lives and be agents of change. Currently, girls in Latin America are likely prone to three phenomena – all of which have negative consequences for their future well-being and the one of their children:

- One in three girls (ages 18 – 24) in Latin America, totaling well over 18 million young women, are out of school and out of work (or NEETs, which stands for Not in Education, Employment, or Training);

- Latin America is one of the regions with the highest teenage pregnancy rates worldwide ;

- And finally, about one in four girls in the region is married by the age of 18 (or living in a non-matrimonial union). Brazil, for example, ranks 4th on the list of countries worldwide with the highest absolute number of child marriages.

Those phenomena, I’d like to argue, are deeply interconnected, and all have negative consequences for the future well-being of girls and their children. Being a NEET, having a child as a teenage girl, and getting married by age 18 are related to traditional roles for women, to exclusion and to a lack of opportunities.

In Brazil we tried to address these issues in a recent pilot World Bank initiative with the State Education Secretariat of Rio de Janeiro and Promundo.

Becoming agents of change

Again – what does this have to do with ‘hope’? Prior to starting the pilot intervention, we had conducted a qualitative study on the subject of women NEETs in Brazil and found that they often referred to themselves as recipients rather than agents of change. Also, their aspirations were largely framed around becoming a mother and a ‘dona de casa’ (English: homemaker) – with implications for pursuing teenage pregnancy and early marriage.

In the absence of role models, opportunities and support systems, many young women in Brazil – and in the region overall, particularly those in poverty - may aspire to becoming homemakers rather than economically independent and agents of their own fate. This by and large is due to structural constraints (poverty, exclusion, traditional gender norms).

The pilot project “Designing Futures” aimed at supporting girls to stay in school and form aspirations linked to education and work. It is only fitting to talk about it as the world gears up for this year’s International Day of the Girl, which comes under the theme “My voice, our equal future”, and highlight the need for girls to learn new skills towards the futures they choose.

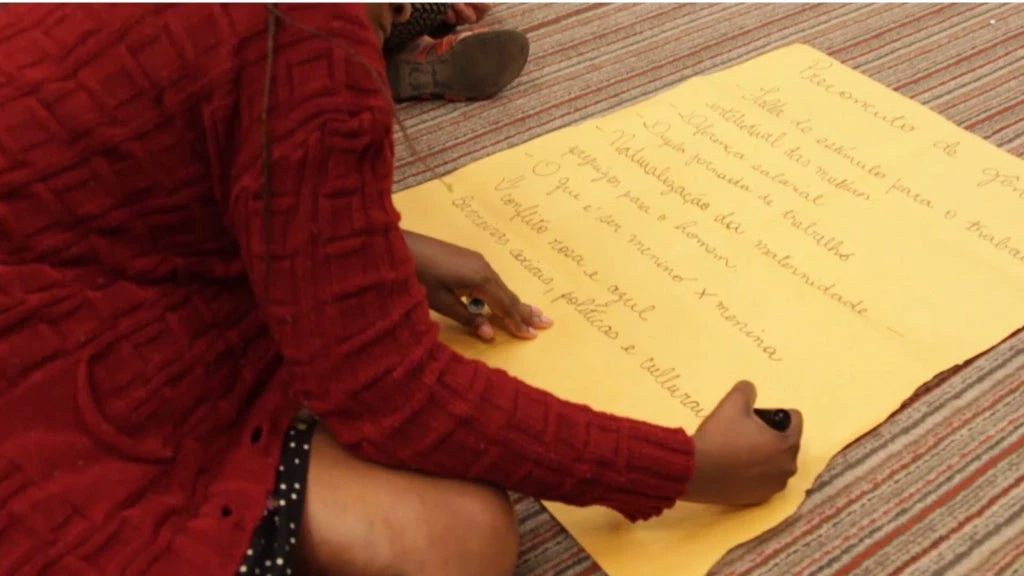

“Designing Futures” was applied in two schools (one in Complexo do Alemão, a conglomerate of 14 poor communities, and one in the Rio de Janeiro suburb of Cascadura) to overcome the obstacles girls face in transitioning from secondary school to tertiary studies and/or into a job. About 250 students were reached in total.

A toolkit and training guide for educators were developed, helping teachers foster dialogue with their students about more equitable relations between men and women, time use and division of labor at home, the world of work (and barriers and opportunities associated with it), and possibilities for continuing education.

Plan the future now

After the first round of implementation, the feedback was overwhelmingly positive, with teachers suggesting that absenteeism had decreased, that students were recognizing the value of completing education as well as the importance of getting a (good quality) job. School had become a place where the students felt a sense of community, where they felt ‘heard’ according to the qualitative evaluation.

“I do plan my future now. I won’t just wait for tomorrow. Now is now,” said one girl who participated in the pilot. Others shared how boys in the classroom had revisited their sexist attitudes and behaviors towards their female classmates. “The students saw themselves as the protagonists of their own lives,” a teacher commented. And finally, the principal of one of the schools said: “Now it’s a different class, a different history, a different willingness to live”.

The urge for action is clear: Not addressing this issue may not only bring negative consequences for young women, it can contribute to the creation of poverty traps. Young (poor) women in the region need to be exposed to role models, to opportunities available to middle-class girls, and to educational environments supportive of their role as an agent in their own lives. This is what we aimed for in “Designing Futures”.

The fact that these girls (and boys) gained hope through this pilot is reflected in their strengthened commitment in class, their engagement in school, their improved performance and their expressed willingness to take control of what comes next. Truly and most certainly, structural constraints these young people are facing need to be lifted simultaneously. This includes improved educational opportunities, quality jobs, safe transportation and care institutions for those that have children already.

The very positive experience with the pilot so far plants hope. We hope that change is actually possible, and that girls in Brazil, and in Latin America more broadly, can have better futures.

Join the Conversation