The hyperactive 2020 Atlantic Hurricane season has added an extra layer of uncertainty to countries in Latin America and the Caribbean already grappling with debilitating impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic. The frequency of storms this season has been so extraordinary, that the 21 available letters reserved for naming storms were exhausted by mid-September. Greek letters are now being used for only the second time in history.

Covariate shocks including disasters, economic crises, and pandemics threaten to reverse decades of gains achieved in poverty reduction and shared prosperity in the region. These shocks tend to disproportionately affect the poor and push near poor households into poverty. Recent analyses show that an increase in hurricane intensity in Central America caused extreme poverty to rise by 1.5 %; droughts in Nicaragua increased the probability that households would remain trapped in poverty by 10 %. In the Caribbean, at least one country is expected to be hit by a major hurricane each year; and Hurricane Maria in 2017 threatened to increase poverty in Dominica by 14 % if consumption impacts were not addressed.

When crises hit, poor families tend to adopt negative coping strategies, such as reducing food consumption and taking children out of school. These challenges have been evident in the current COVID-19 crisis. Over 170 million children in the region are out of school due to closures; 14 million people are at risk of reduced nutrition; 25 million jobs could be lost; the number of unemployed persons in the region could increase to 37.7 million, and 29 million people are expected to find themselves in poverty.

Given the increased risk and pervasive shocks, Latin American and Caribbean countries need more deliberate interventions to invest in human capital, facilitate economic inclusion, and build resilience . Social protection has been key to supporting these objectives in the past and are even more vital now. Around 50 % of the region’s population is covered by some type of social protection and social assistance transfers have reduced poverty in Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Mexico, Panama, and several other countries.

By making social protection systems ‘adaptive,’ countries in the region can help households better prepare for, cope with, and adapt to shocks and ensure that they do not fall (deeper) into poverty . Indeed, governments in the region have routinely leveraged their social protection systems to respond to varied crises. Most recently, countries used these systems to respond quickly and innovatively to address income and welfare effects of COVID-19, with 184 social assistance measures, 45 social insurance measures, and 28 labor market measures introduced by late September.

Despite these innovations, Latin America and the Caribbean countries still face challenges. These include, inter-alia, effectively scaling up safety net coverage for shock response; a lack of adequate protections for informal workers; dependence on rudimentary information systems and inadequate identification systems in some countries; weak coordination and monitoring; inflexible benefit delivery mechanisms, and inability to adapt to nuanced post-shock contexts.

What can the region do to build more shock-responsive social protection systems?

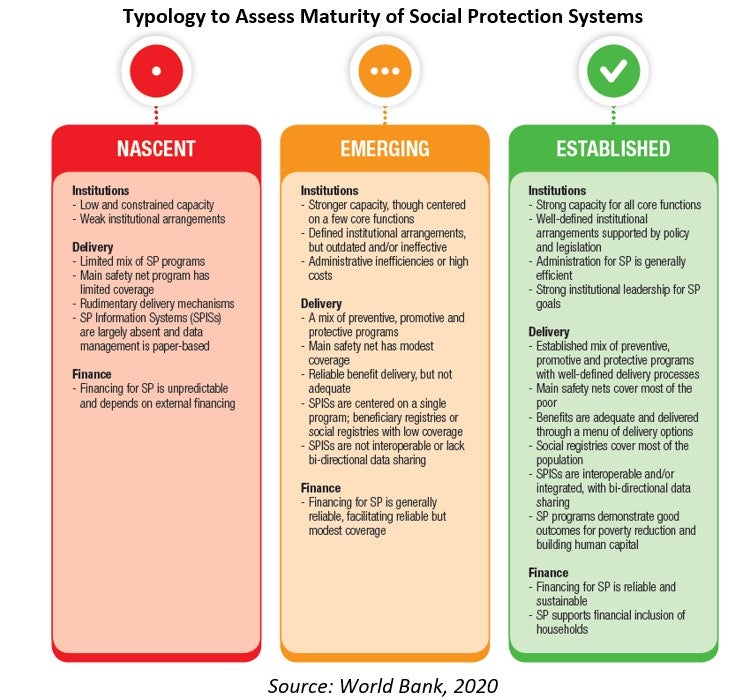

A recently published series of guidance notes offers practical recommendations. The synthesis note provides a framework for Latin America countries to assess the maturity of their social protection systems along the three critical dimensions of Institutions, Delivery, and Finance. The notes also argue that social protection can contribute to risk identification and reduction, preparedness, resilient recovery, and financial protection.

First, improving identification and coverage for targeted safety nets is critical, since this is often the fastest mechanism to respond to the poorest when shocks occur . Where programs cover too few of the poor, increasing benefits to existing beneficiaries has little impact. A note on Tailoring Adaptive Social Safety Nets offers key design considerations to better use non-contributory cash and in-kind transfers to support shock-response, coping, and adaptation among poor and vulnerable populations.

Countries also need to ensure that there is reliable data on poor and vulnerable households, including those with increased risks to varied shocks . This will help inform interventions to improve resilience among these households and enable rapid expansion of benefits to uncovered households. A note on Making Social Protection Information Systems (SPISs) Adaptive offers guidance on improving and using social registries, beneficiary registries, and other SPISs to support risk management objectives, particularly through more focused integration and interoperability with risk information systems.

Improving post-disaster assessments among affected households is also important. A note on Post-Disaster Household Assessments shares country experiences in using these instruments and guidance on better use of this data to inform post-disaster support.

Using Social Work Interventions to leverage the frequent interaction between social workers with beneficiaries and clients of social protection agencies is also essential, as it supports more focused resilience building and shock responses.

Finally, ensuring financing to support effective social protection response is paramount. A note on Leveraging Disaster Risk Finance provides important country experiences and recommendations on this topic.

Join the Conversation