Students from Panama

Students from Panama

Visiting Panama City, one is struck by the beauty of its modern infrastructure. But behind this more visible side of development lies a stark reality: 67 % of the Panama´s children are not able to read and understand a simple text by age 10.

Why should the country care? Well, if a country’s people are not productive, economic growth is limited. The World Bank’s Human Capital Index (HCI) shows that the productivity losses due to the poor level of human capital in the country is significant. On average, a child born in Panama today is expected to be only 53% as productive as she could be if she had access to a high-quality education and good health.

More so than quite a few other countries in Latin America, Panama has recently shown a strong commitment to measure learning at scale . Since 2016, the national education evaluation system has been implementing the “Prueba CRECER”. CRECER is a census-based standardized student learning assessment that measures competencies in reading, math, and science for students in the 3rd and 6th grades of primary school. The frequency and coverage of the CRECER assessments is impressive by any international standard.

Nonetheless, large discrepancies in learning exist between rich and poor, and urban and rural students. Nationally more than three in five students in Panama do not reach basic reading proficiency by age 15. This puts a 15-year-old student in Panama four years behind the schooling of a student in an OECD country. Poor students score almost four years of schooling behind rich students. Mirroring the geographical inequalities in Panama, students in rural areas score more than two years of schooling behind those from urban areas. These numbers suggest that Panama’s education system is one of the most unequal in the Latin America region.

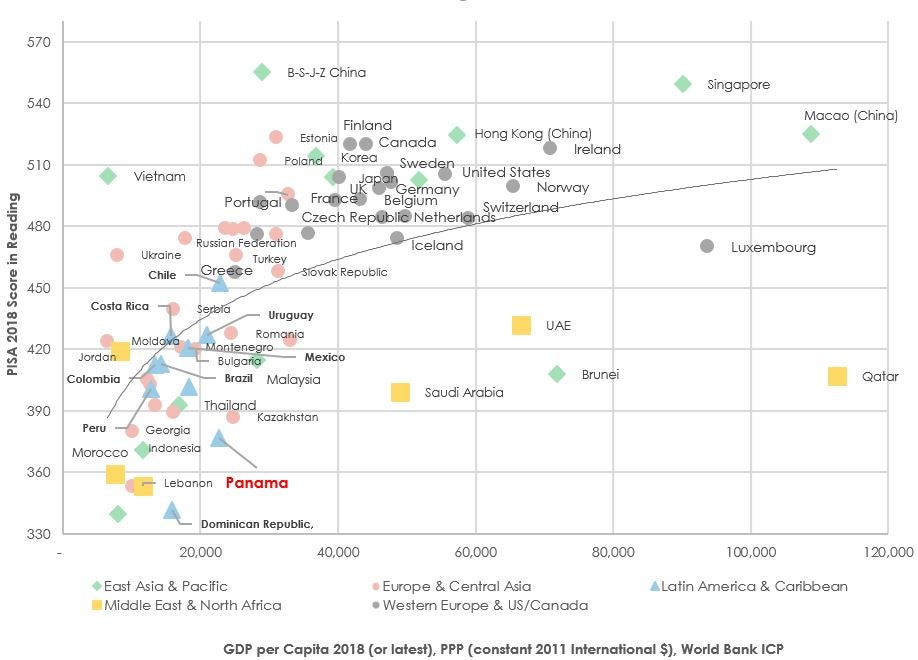

And Panama’s learning levels are behind those observed in countries with similar levels of income. Students in Croatia, Russia, and Bulgaria which have similar levels of income are, on average, two years of schooling ahead of students in Panama (Figure 1). The same is true for countries in Latin America. Students from Panama perform one year of schooling behind the average student in Latin America.

The data collected through CRECER presents a great opportunity for the country to develop evidence-based strategies that place learning (not school attendance) at the center. The international evidence shows that the use of student learning assessments as a diagnostic tool can help schools improve learning outcomes, even in a relatively short period of time. Student learning assessments can help schools understand where their main challenges are, serve as key inputs for the preparation of school improvement plans, and help policy makers design more relevant pre- and in-service teacher training. Also, learning assessments can serve to develop education interventions that target schools with higher learning deficits.

The CRECER data can further be leveraged to build a long-term strategic vision placing learning at the center of the education system in Panama . The existing learning crisis in the country not only wastes the potential of the next generation of Panamanians but it also hurts the economic perspectives of the country. Eliminating learning poverty in the country should be a priority and policy actions should be aligned with this urgency. Although the magnitude of the challenge is large, addressing it is possible. Establishing realistic but ambitious learning targets is a necessary condition. The first step to reforming an education system is to align all stakeholders—and the education system itself behind the learning target.

With a new political cycle in place, Panama stands poised with options for significant education reform whose impacts on learning can be well monitored. The country faces a big challenge to diversify and increase the competitiveness of its work force. To achieve a more sustainable economic growth model, Panama will need to invest more in its people, giving them opportunities to become more adaptable, competitive, and innovative workers. And the CRECER data can and should be used to place learning at the center of the education system.

Join the Conversation