Istock. Photo: Antonio Guillem

Istock. Photo: Antonio Guillem

Lucia is a young woman with long hair and pink sneakers. Unlike her classmates, she had to miss classes to go to a medical check-up. At 16, she is pregnant. Lucía's doctor says that she will have to perform a cesarean section, given her size, as she would not withstand a natural birth. Like many in her situation, Lucía will end up dropping out of school.

According to the 2020 Population and Housing Census, more than 535 thousand young women between the ages of 15 and 19 in Mexico were mothers. Teenage pregnancy is the third main reason why young women drop out of school (ENADID, 2018). Fewer years of education eventually reduce the income of these women in the long term.

It is true that there has been progress in this regard in Mexico: the 2020 Population and Housing Census shows a drop in the adolescent fertility rate when compared to the results of the 2015 Intercensal Survey and also a change in the upward trend observed among 2010 and 2015. Between 2010 and 2015 the adolescent fertility rate increased from 56.9 to 62.5 births per 1,000 adolescents between 15 and 19 years old, but from 2015 to 2020 there was a decrease to 43 births per 1,000 adolescents, a substantial drop in just 5 years.

However, the adolescent fertility rate remains high as there were more than half a million mothers between the ages of 15 and 19 in 2020. In fact, Mexico has one of the highest teenage pregnancy rates among the countries that make up the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

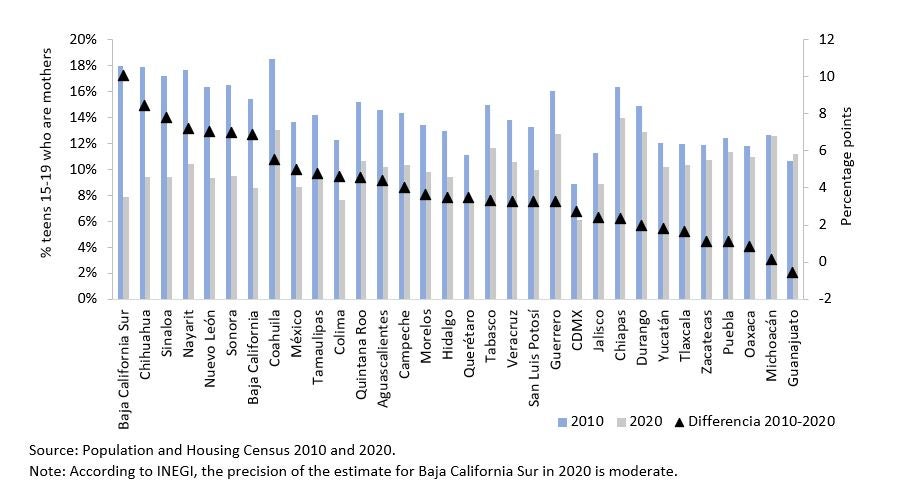

Furthermore, this progress varies across Federal Entities. The main improvements were concentrated in Baja California Sur, Chihuahua, and Sinaloa with 10, 8.4 and 7.8 percentage point declines in teenage fertility rates compared to 2010, respectively. On the other hand, Oaxaca, Michoacán, and Guanajuato did not see any improvement. Likewise, there is high heterogeneity at the municipal level. For example, in four states—Chiapas, Guerrero, Coahuila, and Sonora—more than a third of the municipalities have adolescent pregnancy rates above 75% of the distribution, while in Baja California and Mexico City, more than 60% of the municipalities had rates that are below 25% of the distribution.

Teenage pregnancy rates and progress in the indicator during the last decade, by Federal Entity, 2010-2020.

A problem associated with the well-being of the home

Teenage pregnancy in Mexico is mainly associated with household poverty and with the presence or absence of the parents , in line with the evidence in Latin America. Using the 2020 census, we estimate the determinants of teen pregnancy based on individual characteristics.

At first glance, our analysis finds that a young woman who lives in a rural area or who is indigenous is more likely to be a teenage mother. However, when household welfare variables are considered (such as housing conditions or possession of assets), ethnicity and rurality cease to be risk factors. These results suggest that adolescent pregnancy is associated with household well-being and has less to do with being indigenous or living in a rural area.

National and international evidence is clear regarding the negative impacts of adolescent pregnancy on human capital development . Various studies have found a significant association between early motherhood and lower educational attainment and poorer labor market outcomes for women. This association implies that an adolescent mother will see her opportunities affected not only in the short term but also in the long term, reinforcing gender gaps.

The actions that have proven to be effective in reducing adolescent pregnancy include sexual and reproductive health policies, educational programs among peers and/or at school, empowerment and training activities , school retention programs (conditional transfers, extended school programs) and behavior change campaigns.

Our analysis, in the report Women's Labor Participation in Mexico, shows that both friendly service centers and the availability of doctors per medical unit are related to a lower probability of teenage pregnancy.

How to prevent these pregnancies?

Despite advances in the prevention of teenage pregnancy, there is still much to be done. The pandemic has exacerbated the risks that existed for adolescents and young people, which may be affecting recent progress in reducing teen fertility rates. The Mexican government has set a goal to reduce the adolescent fertility rate for 15 to 19 years of age by 50% by 2030 and to reduce fertility rates among girls ages 10 to 14 to zero.

To this end, the National Strategy for the Prevention of Adolescent Pregnancy (ENAPEA) prepared in 2019 and currently in the process of implementation defines a series of actions with a multisectoral approach to curb this phenomenon. While the strategy is on the right track, it will be important to:

- Expand and ensure access to sexual and reproductive care centers for adolescents, mainly in high-risk municipalities. In the context of COVID-19, ensure young people can safely access them.

- Ensure school attendance and quality education to produce a change in the opportunities and aspirations of adolescents and young people. This includes targeted financial supports that can help to ensure school attendance.

- Promote the socio-emotional and technical skills development of adolescents and young people. Support actions that provide greater opportunities for continued education through the development of skills for work and life, including remedial actions that address basic skills deficits.

- Explore strategies for extended day school programs to change the use of time by adolescents and young people.

- Use mass media to provide educational content and establish better social norms. It is important to ensure that the messages are of interest and that they are adapted to different populations.

Join the Conversation