Producer collecting coffee beans from the coffee tree. Source: Canva Bank of images.

Producer collecting coffee beans from the coffee tree. Source: Canva Bank of images.

“Our coffee has been sold in Europe for four years: exporting is costly, but the good prices we receive make it worth it for our families.” Genaro Juarez, president of the Entre Cerros Cooperative in the mountains of the San Marcos department of Guatemala, has no doubts about the benefits of exporting his premium coffee to the European market, and dreams about expanding his business to processing activities that will grant him higher profit margins.

The European Union (EU) has introduced new legislation to prevent imports of commodities contributing to deforestation. One of the commodities affected is coffee, a key export of Central American countries . Coffee represents 14 percent and 52 percent of total agrifood exports in Guatemala and Honduras respectively, and a fifth of all exported Guatemalan coffee and half of the coffee exported from Honduras are destined to the EU. The new EU regulation is thus very relevant for these two countries, and in particular for their many smallholder coffee producers.

What is the new EU regulation?

According to the European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), at the end of 2024, it will be possible to place on the EU market certain commodities (cattle, cocoa, coffee, oil palm, rubber, soya, and wood) only if they are:

- Deforestation-free: produced on land that has not been subject to deforestation after December 31, 2020

- Legally produced: produced in accordance with the relevant legislation of the country of production

Those importing products in the EU market (the “operators”) will be required to prepare a due diligence statement, including geolocation and date of produce, identification of the supplier, and verifiable information that the products are deforestation-free and legally produced. Operators are also expected to assess non-compliance risk and to show proof of risk mitigation measures.

What does this mean for coffee produced in Guatemala and Honduras?

Given the complex mechanisms behind deforestation, assessing the extent to which coffee cultivation is a driver of deforestation in the two countries is not straightforward . With this caveat in mind, overlapping forest monitoring and coffee production maps indicate that, of the total area of forest loss in each country since 2000, 8.3 percent and 12.3 percent were located in coffee-growing areas of Guatemala and Honduras respectively. Similar back-of-the-envelope estimates suggest that only a minority of coffee-harvested areas in the two countries may be non-compliant with the EUDR.

The challenge, however, lies in the deforestation-free due diligence process requested by the EUDR, which would rely on traceability and information systems that a fragmented value chain may find challenging to comply with.

The coffee value chain in Honduras and Guatemala comprises primarily poorer, smallholder farmers: 90 percent of Guatemalan and 70 percent of Honduran producers operate less than 2 hectares, and around two-thirds of them live below the national poverty lines. Despite its laudable objective, as of today the EUDR thus risks excluding from the EU market poor and underequipped farmers, who do not have the means to document their deforestation-free status .

“We have talked with our buyers in Germany and we have to georeference all our coffee plots,” explains Arcadio Galindo, a smallholder coffee producer from the Chajulense Cooperative in Quiché, Guatemala. But while Arcadio hopes his cooperative to be up to the challenge, several more may not be.

Strong institutions to build on

The institutional sectoral environments in Guatemala and Honduras contain important repositories of data and technical capacity that could facilitate low-cost investments toward traceability mechanisms for coffee actors. In both countries, the main coordinating institutions in the coffee sector have a strong institutional presence and are partnering with other sectoral actors to provide key commercial services and develop digital tools for extension and geo-referencing.

However, challenges still limit sectoral coordination and information sharing, in particular for the many farmers at the geographic and productive margin that are less integrated into the value chain .

What can be done?

In both countries, targeted investments and public-private sector-wide systems could reduce the burden of generating evidence on individual actors, and facilitate access to verifiable information about land use and deforestation:

- Public institutions should develop and manage national forest monitoring systems, tracking of coffee growing areas, and farm registries that can provide reliable maps and real-time assessments of the scale of deforestation, land use, and location of coffee plots.

- Lessons can be driven from other value chains that have developed measures to ensure traceability. In Honduras, certification processes have been developed for timber and livestock that involve geo-location of the origin of produce, and current protocols exist for phytosanitary controls in the coffee sector.

- It will be paramount to increase the connectivity of farmers through digital tools and communication from key sectoral institutions. Producers' organizations and cooperatives, formal intermediaries, and public sector entities can play a crucial role in centralizing and distributing knowledge and services and providing technical assistance to farmers.

The importance of coffee production to rural livelihoods and the opportunities presented by the European market motivate a closer look at potential responses toward compliance with the EUDR. There is a need to invest smartly - in digital innovation, capacity, and human capital - to build a sustainable, inclusive, and integrated coffee value chain in Central America.

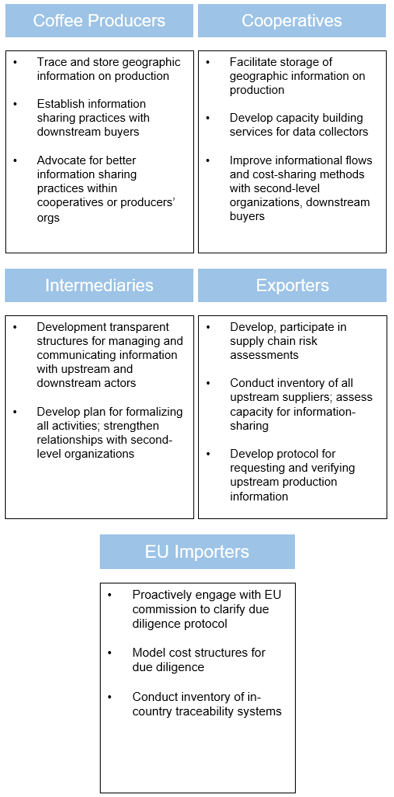

Recommendations for private sector stakeholders

To receive a weekly article ,

Related articles

Join the Conversation