Trabajadores de Honduras en el marco de un proyecto de donación

Trabajadores de Honduras en el marco de un proyecto de donación

When COVID-19 shut down the clothing store in Panama City where Maria worked, at first, she was not concerned. While informal, her job meant she had enough to cover basic needs. Now Maria faces unexpected challenges. How would she pay for food and rent? Would she be able to find a new job? Who could help?

Maria was one of hundreds of thousands of workers across Central America asking those questions. A recent World Bank report, Stronger Social Protection and Labor Systems in Central America for a Resilient and Inclusive Recovery, examines how the pandemic stretched social safety nets, other income protection initiatives and labor market programs in the region, surfacing gaps and new priorities. The report makes the case that strategic investments in Social Protection and Labor (SPL) systems lay the foundation for stronger, more inclusive growth in Central America and build resilience as poor and vulnerable people, like Maria, confront increasing shocks beyond the pandemic.

Pre-pandemic challenges in Central America

Despite progress toward more comprehensive SPL systems, many Central Americans had limited pre-pandemic access to vital programs to help them cope with crises, find jobs, invest in the health and education of their children, and protect the elderly .

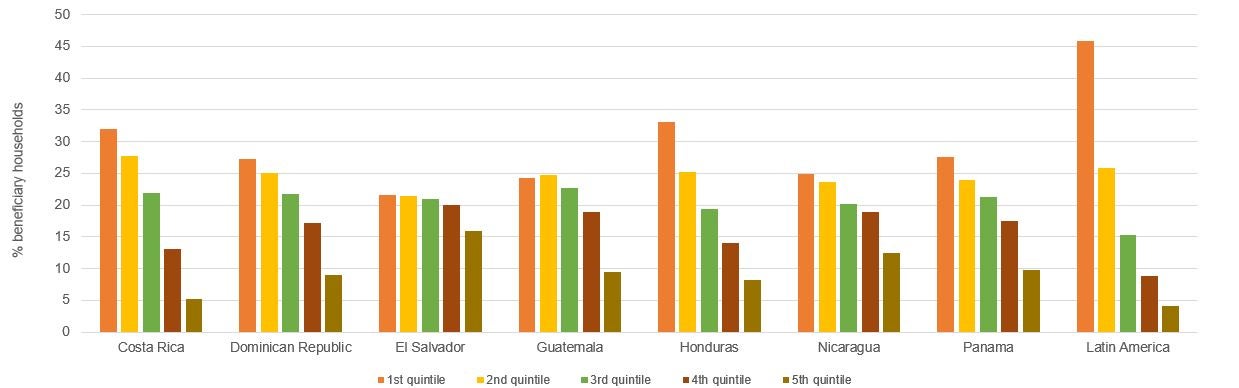

Most Central American countries spent less than the regional average on social assistance and focused on broad initiatives with high coverage of both rich and poor people . For example, at least one social assistance program benefitted 67 percent of the wealthiest 20 percent of people in El Salvador and 32 percent of this same income group in Panama, compared to the Latin American and Caribbean average of 10 percent.

Better-targeted programs, such as conditional cash transfers, reached only a small proportion of poor people, from 4 percent of those with the lowest 20 percent of incomes in El Salvador to 44 percent in Costa Rica, below the Latin America and Caribbean average of 49 percent.

Distribution of program participants by income quintiles, all social assistance, by Central American countries and Latin American and Caribbean regional average

Adding to the difficult landscape for vulnerable Central Americans before COVID-19, most jobs in the region were low-quality, and informal, with lower-skilled workers, youth, and women experiencing worse job outcomes. For example, despite recent gains, women represented most of those not in employment, education, or training in Central America, from slightly less than two-thirds in Costa Rica to around 80 percent in Honduras and Guatemala.

Responding to COVID-19 in Central America

The arrival of COVID-19 resulted in significant setbacks for Central American economies and workers . Already disadvantaged youth, lower-skilled workers, and women faced disproportionate impacts, sustaining higher job losses that deepened divides and threatened to scar large swath of workers with decreased lifetime earnings. Pandemic impacts on women were acute; in Costa Rica, women experienced a 28 percent drop in employment in the first quarter of the pandemic as compared to a 17 percent decline for men, with lower-educated workers experiencing declines of more than 40 percent, with only the highly educated virtually unaffected.

Changes in employment and participation rate in Costa Rica, 2020-2021, by education and gender

Like in other parts of the globe, Central American governments responded by leveraging existing SPL instruments. However, programs struggled to protect existing participants and expand coverage to the “missed middle,” or newly vulnerable people who normally fell outside of both safety nets and formal systems that can act as stabilizers during shocks. Given the limited adaptiveness of systems and vast needs, some governments had to create parallel systems to act swiftly.

Almost all countries in the region deployed cash transfers mainly to reach new program participants, including informal workers. Only the Dominican Republic deployed data from its social registry, with other countries relying on approaches ranging from on-demand applications in Costa Rica to new data sources such as utility consumption in El Salvador and Guatemala. Panama launched one of the largest-scale cash transfers – Plan Panamá Solidario –by matching different administrative databases to identify participants. On the other hand, social insurance initiatives were limited due to narrow coverage and the lack of unemployment insurance.

Labor market measures included access to credits in El Salvador and Panama and guarantees in Costa Rica for micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises; wage subsidies or similar support for formal workers in Guatemala, the Dominican Republic, Honduras, and El Salvador and training in Costa Rica and Panama. COVID-19 also catalyzed payment innovations, including increased digitization such as virtual accounts for emergency transfers in Guatemala’s Bono Familia.

More resilient and inclusive social protection and labor systems

The pandemic demonstrated the importance of adaptive and effective social protection and labor measures for a resilient and inclusive recovery . Based on global evidence, the report points to three policy directions for SPL systems in Central America:

- Improve the efficiency and effectiveness of social protection spending and ensure the right mix of programs to protect and build the resilience of the poor and (newly) vulnerable. Countries should move from weakly to well-targeted programs, which often have additional benefits to people’s human capital.

- Improve adaptiveness of SPL systems and strengthen delivery systems. These steps could include expanding social registries, supporting dynamic inclusion, and using digital payments.

- Strengthen employment services and institutions to support people to return to (productive) jobs quickly. Governments can better understand and monitor labor demand and promote private sector–led training to improve employability and better job matches.

Stronger SPL systems in Central America are urgent in the context of multiple global crises from the Ukraine war to inflationary pressures, as well as natural hazards and climate shocks in the region that have been increasing in frequency and intensity with greater impacts on the poor and vulnerable, and significant economic losses. As the pandemic illustrated, SPL systems increase people’s resiliency, preserve, and restore human capital, while helping affected workers, like Maria, to return to earning an income, and countries to invest in their people.

To receive one article per week,

Related articles

Join the Conversation