Hombre indígena trabajando en una fábrica en Oaxaca, México.

Hombre indígena trabajando en una fábrica en Oaxaca, México.

The COVID-19 pandemic has upended our lives, and its effects on jobs have remained across Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) countries for over two years. Although LAC economies and labor markets started to recover in 2021, employment levels and working conditions undeniably changed.

We looked at household data collected together with UNDP in the first wave of the 2021 LAC High-Frequency Phone Surveys (HFPS) conducted in mid-2021 in our report “Long Covid: The extended effects of the pandemic on labor markets in Latin America and The Caribbean” for insight on these inquiries and draw some lessons.

What has happened to people who lost their jobs due to the pandemic?

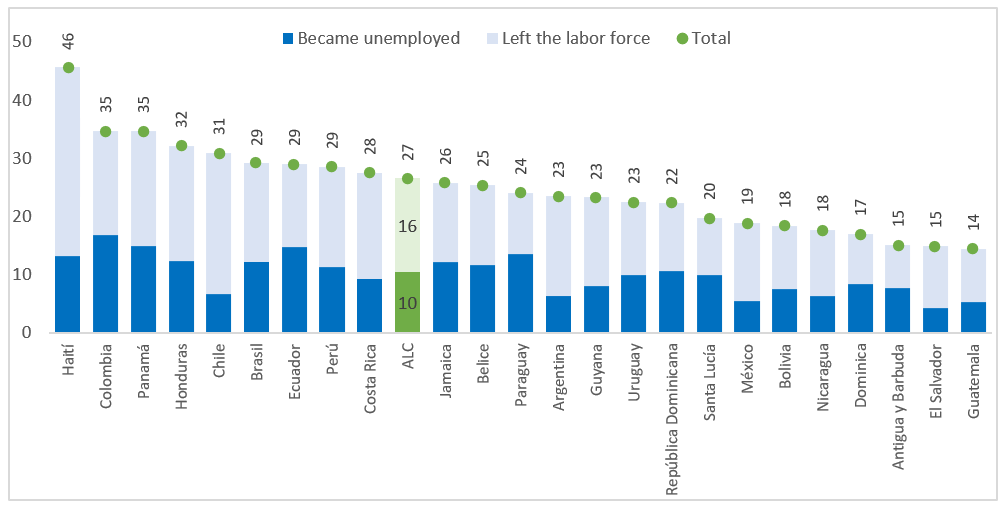

A quarter of adults previously employed were still not working over a year into the pandemic. Many of them left the labor market altogether. This overall abandonment of the labor market was higher in countries such as Chile, Argentina, and Mexico (also Haiti).

By mid-2021, LAC’s average employment rate was 11 percentage points (pp) below pre-pandemic levels; workers in Colombia, Panama, Honduras, and Chile saw a vast deterioration in their situation. Workers in Haiti also experienced significant losses, but the confluence of structural challenges makes it hard to attribute it solely to COVID-19.

As is often the case during crises, those already vulnerable were the most affected. Women were hit the hardest by Covid-19, with 38% of them having stopped working in mid-2021 compared to 17% of men, and significantly more women than men shifting from employment into inactivity (about 14 percentage points). Yet the most considerable job losses were experienced by mothers with small children (0-5 years old) (40%), who have borne the weight of increased childcare responsibilities and unpaid housework.

Youth (18-29 years) and the elderly (65+) also suffered higher job loss rates (29% and 31%) than their middle-aged counterparts (30-54 years) (22%). And while most of those younger workers kept looking for a job, over three-quarters of older workers who stopped working by mid-2021 left the labor market.

How about the quality of the jobs?

Compared to pre-pandemic, LAC workers were returning to a different job market in mid-2021. While fewer people worked for large and medium-sized firms, more moved to micro-firms and self-employment. Weekly paid work hours decreased while informal work increased. Panama, Peru, and Haiti experienced the most significant employment shift to micro-sized firms, and employment in large firms shrunk most in Panama and Costa Rica.

Self-employment also rose five percentage points LAC-wide, especially in Haiti, Panama, and Peru. The share of formal employment across the region also decreased by about five percentage points, with Panama, Nicaragua, and Peru most affected. Finally, average working hours declined from 43 to 37 hours per week region-wide.

Some policy implications

The LAC region already had a disproportionate share of workers in self-employment and micro businesses, so an additional shift of workers away from larger firms is not favorable. Evidence shows that increasing informality decreases income from work—ultimately rising inequality and limiting economic growth.

While some people who weren’t working before the pandemic found opportunities to work after the first year of the pandemic, inactivity rates remained higher than before the pandemic in most countries. While it is possible that the pandemic changed how households make decisions, this could also result from economy-wide consequences such as lower real salaries, stagnated labor demand, hybrid schooling, etc.

Although more country-level research is needed, policymakers might have to consider actions to bring younger workers and women back into the labor market.

A post-pandemic world of work might require new arrangements, affordable childcare options –especially for activities that require in-person interaction–, flexibility to work from home or hybrid approaches , and widespread digital connectivity, among other actions.

Join the Conversation