Understanding poverty and reversals in five charts on Niger

Understanding poverty and reversals in five charts on Niger

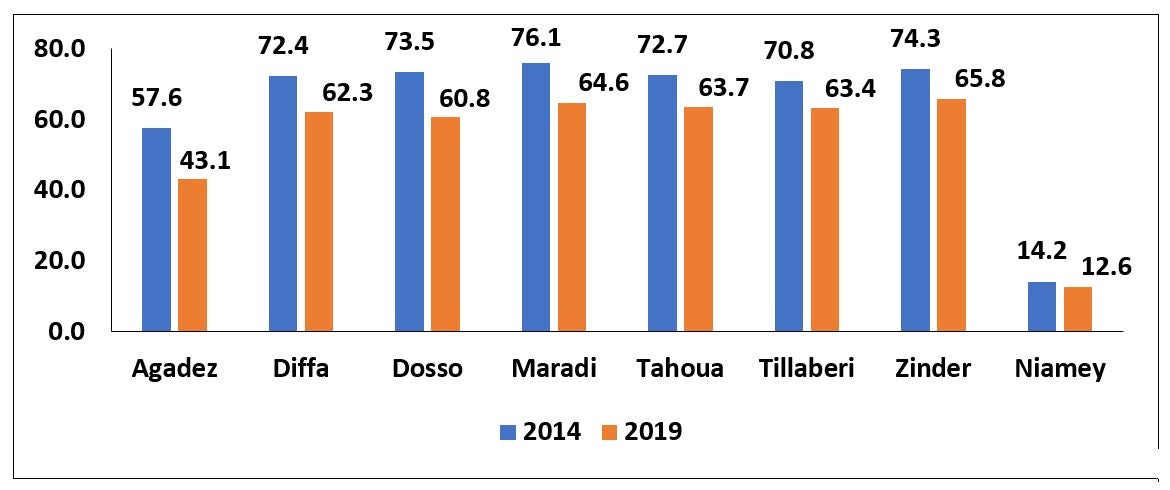

Niger made progress in poverty reduction between 2014 and 2019, experiencing accelerated economic growth from 2015 onward. Agriculture, which employs most of the country’s poor, has been the main driver, ahead of industry, manufacturing, and services. As a result, poverty dropped by 5.4 percentage points, particularly in rural areas, and the percentage of people living in multi-deprivation—defined by health, education, electricity, water, sanitation, housing conditions, and asset ownership—dropped from 70% to 60%.

Growth in consumption also favored the poorest, leading inequality to fall from 36.9% in 2014 to 35.0% in 2019. But, despite these improvements in non-monetary dimensions of welfare, Niger is still underperforming, with limited access to basic social services.

Figure 1: Nigeriens living in multi-deprivation declined across all regions

Notwithstanding progress during 2014 to 2019, poverty remains endemic in Niger, and the COVID-19 pandemic and economic downturn it has caused have reversed many of the recent gains. In 2019, two in five Nigeriens (40.8%) lived below the national poverty line, most (95%) in rural areas, with the incidence of poverty much higher in rural areas (46.8%) than in the capital Niamey (7%) and other urban areas (11.8%).

In 2020, losses in income from COVID-related job layoffs and lower remittances reversed the poverty reduction trend. For the first time in decades, the rate of extreme poverty increased in 2020 to an estimated 42.9%, affecting more than 10 million people. While the poverty rate is expected to stabilize in 2021 and 2022, the absolute number of poor in Niger is projected to continue to increase because of rapid population growth. In addition, the pandemic has constrained household access to basic services, such as health and education.

Figure 2: Poverty prevalence is highest in Dosso, Zinder, and Maradi regions

As the country’s largest employer, agriculture, including farming and livestock, dominates rural Nigerien household incomes. Contributing to 40% of GDP, it employs 75% of Niger’s workforce. The sector is dominated by food crops, particularly rainfed cereals (representing 40% of rural household income), lower than the Sub-Saharan African average of 68%. Livestock generates about 6% of rural income, reflecting the fact that 95% of rural households own or keep animals.

Rural households also derive about 20% of their total income from non-farm enterprises, with trade, services, electricity and water the main sectors of income generation common to all wealth groups. Yet, only 16% of Nigerien households have access to electricity, compared to an average of nearly one in two in most of Sub-Saharan Africa.

Figure 3: Share of income from different sources, by region

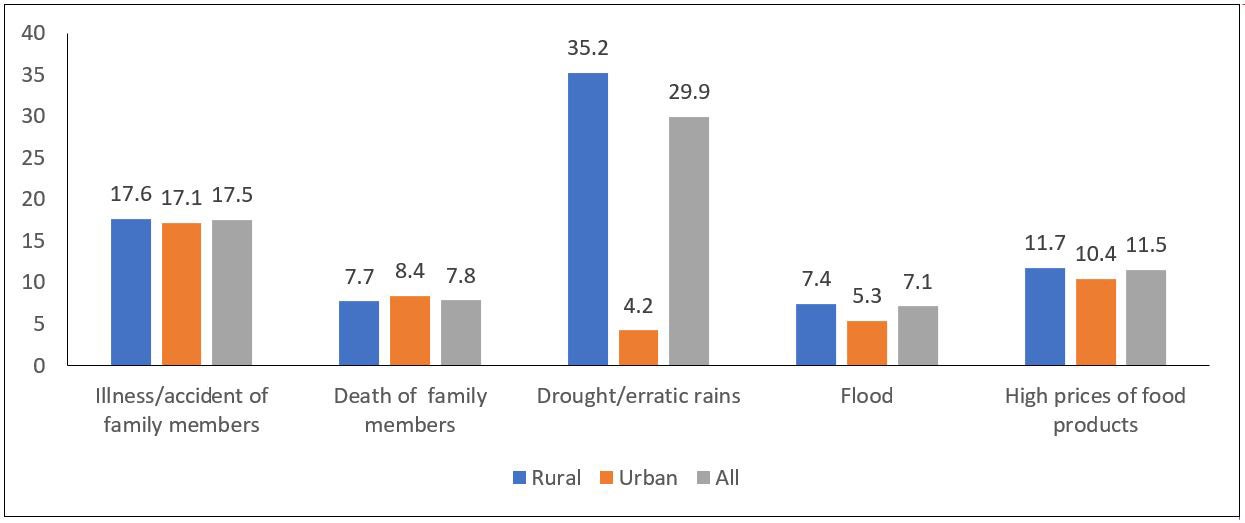

Natural hazards pose major challenges to Nigerien agriculture, and only a few households have effective coping mechanisms to deal with them. Their most common strategies are to rely on friends and family (19%), the sale of livestock (19%), and savings (18%), signs that formal social safety net programs have limited coverage. In rural areas, many households typically reduce their consumption following adverse events, leading to a negative impact on their children’s nutrition and human capital.

Niger is one of the hottest countries in the world: the rainy season is very short, typically lasting a single two-month period, and the country experiences seasonal flooding. In 2019, flash floods—particularly in Agadez, Diffa, Maradi, and Zinder—affected over 259,000 people, disrupting livelihoods and causing livestock losses.

In 2011, following a severe drought, losses of crops and livestock pushed nearly half of all Nigeriens into a state of high food insecurity. The phenomenon returned a few years later, with 35% of the rural population and 4% of the urban population reporting drought as a key shock in the three years running up to 2018/19, according to data from the 2018/19 harmonized households survey.

Figure 4: Proportion of households exposed to shocks

Reducing the gender gap also remains critical for the fight against poverty. Most Nigerien households exhibit gender gaps despite government efforts to narrow them. Girls’ education suffers after primary (elementary) school from, among other things, early child marriage and teenage pregnancy.

Figure 5: Literacy rates by gender and age group

This discrimination persists into adult life, when Nigerien women are more likely to be employed in lower paid informal jobs, mainly in subsistence agriculture, and to earn 29% less than men for similar work. Social bias limits their access to land and chances to own property. And non-farm enterprises owned by women reap 61% lower profits than those owned by men.

Despite some progress in poverty reduction during the last decade, poverty remains prevalent in Niger, particularly in rural areas, and the covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated the situation. Agriculture, which represent the main source of rural households income (40%) faces natural hazard (flood, drought) that limit the possibility of income growth and poverty reduction. Persistent gender gap and low human capital are also major constraint that face Nigerien households.

Join the Conversation