The world has come a long way since Edward Jenner injected a 13-year-old boy with the relatively less severe cowpox virus in 1796, producing a single blister, and then with actual smallpox, producing no disease. In doing so, he provided scientific evidence that vaccination with a mild form of a disease can save people’s lives, paving the way for a striking advance in medicine.

From that pivotal moment over two hundred years ago, human health has improved considerably. Hundreds of millions of children are immunized today against a variety of diseases from smallpox to polio that used to cause widespread death and disability. By 1979, smallpox, a disease which killed 30% of those it infected, was declared eradicated. And polio is now endemic in only three countries.

A country’s capacity to deliver vaccines saves children’s lives

WHO-UNICEF data since 1980 shows progress in child immunization in low-income countries such as Mozambique. For example, only 25% of children had received all three doses of the polio vaccine (POL3) in 1985. With mass immunization, Mozambique reported its last wild poliovirus case in 1993. Immunization with MCV2 (two doses of measles-containing vaccine) has increased sharply in recent years, from 36% when it was introduced in 2016 to 85% in 2019, with the support of Gavi.

Strengthening health systems to provide vaccines efficiently has saved many lives . Immunization gains in Mozambique have contributed to the reduction in child mortality from 266 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1980 to 74 in 2019. Immunization also has broader benefits for society including better student attendance and learning in school. That’s why we do not hesitate to get our children immunized.

The COVID-19 vaccines are critical to keep adults alive and healthy

Today, our greatest challenge is to restart economies and prevent adult deaths and illness from COVID-19 (coronavirus). But can we take 20, 30 or 40 years—or even five years—to achieve the required level of COVID-19 vaccination in our countries? How long can we wait to get to herd immunity, a scenario in which enough people are vaccinated to stop the spread of the disease even if some aren’t vaccinated?

As I wrote earlier, hundreds of thousands of people are being pushed into poverty in Mozambique because of this crisis. Delaying vaccine rollout will be catastrophic for many, with variants contributing to a spike in cases . The latest evidence shows that a more contagious Delta strain of the virus is rapidly becoming dominant in Mozambique as the country enters its third wave, with over 100 deaths in the first 10 days of the month of July, more than the total deaths occurred during the months of May and June combined.

As African governments are trying hard to increase the supply of vaccines coming in, the World Bank has joined the effort. To that end, we have recently approved a $100 million grant in support of Mozambique’s efforts to expand its current COVID-19 vaccination campaign. The funds are being utilized to acquire, manage, and deploy COVID-19 vaccines. This will enable the purchase of approximately seven million doses of COVID-19 vaccines, the single largest contribution for Mozambique’s vaccination efforts thus far.

However, we will have to do more to ensure that people want to take the vaccines. All the vaccines are effective in preventing death and severe forms of the disease in the population. Data shows that if infected, fully vaccinated people have a lower viral load than unvaccinated people and are less likely to develop severe forms of the disease or die from Covid-19. Increasing vaccine literacy is critical, and everyone with any sphere of influence, small or big, can do more to spread accurate information. The vaccines will work to save lives and reopen society only if enough people take them, and if countries can deliver them efficiently.

Despite decades of effort, there are still weaknesses seen even in routine immunization. As Cassocera et al noted in their report on forty years of immunization in Mozambique, national immunization coverage remains below 90%, and Zambézia, Nampula, and Tete provinces have continuously reported low coverage. In some, such as Cabo Delgado, there have been inconsistencies over time.

What needs to be done to gear up for COVID-19 vaccine deployment

We need to learn from the lessons of 40 years. In deploying the COVID-19 vaccines, we need to look at what causes vaccination delays and fix what’s within our control . Even as global supply issues persist, we have to tackle domestic issues around vaccines. It’s not just about finding the money to procure enough doses—an investment that will yield rich returns for the economy—but also about deployment.

A lot needs to be done quickly, from identifying cold chain gaps and closing them, to reducing the rate of vaccine wastage, ensuring adequate distribution of vaccines and related supplies to health facilities, training health workers, and opening effective channels of communication with citizens to ensure that both shots are taken on time in cases where it is a two-dose vaccine.

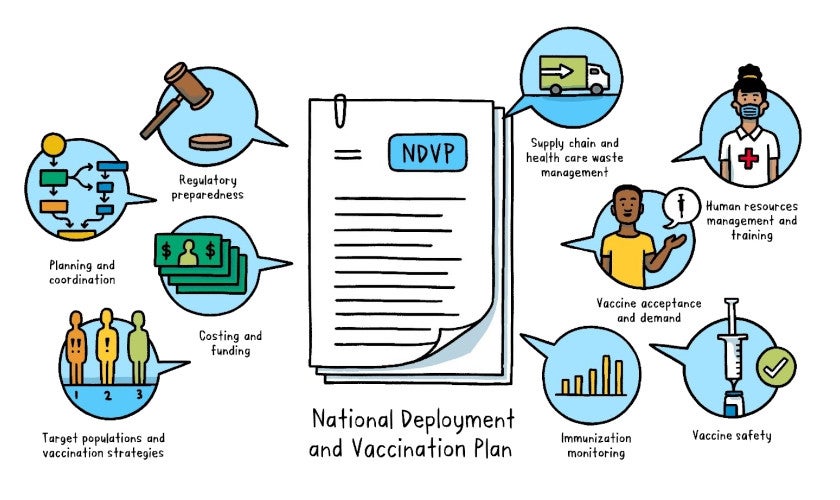

While it may look like we are ready on paper, the process of vaccine delivery can suffer multiple roadblocks. The diagram below shows the various aspects of vaccine management that countries have to quickly strengthen. The World Bank and other development partners are helping countries gear up.

We also know that many countries are experiencing further waves of COVID-19 and that variants are a cause for concern. In addition to vaccination, health systems need to be prepared with hospital beds, oxygen and other supplies, equipment, and know-how on how to tackle cases that require urgent medical attention. We cannot afford the loss of lives and livelihoods that unpreparedness will result in.

While the pandemic is an event of terrible proportions, this generation of children and teenagers should be able to look back on it later as a point after which public health really changed for the better on a historic scale. We have a good shot now at making the world a much safer place for our children.

Join the Conversation